![]()

From

Dictatorship to Democracy:

Venezuela’s Rural Development

Policies before and after Agrarian Reform

De

la dictadura a la democracia:

Políticas de desarrollo rural en

Venezuela antes y después de la reforma agraria

Da

Ditadura à Democracia:

Políticas de desenvolvimento rural da

Venezuela antes e depois da reforma agrária

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.18861/ania.2024.14.1.3819

MSc.

Arch. Ricardo Avella

Delft University of Technology

Netherlands

R.Avella@tudelft.nl

ORCID:

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5235-2719

Received:

30/04/2024

Acepted: 16/05/2024

How

to cite

Avella, R. (2024). Rural development in Venezuela before and after the Agrarian Reform Law of 1960: differences and continuities. Anales de Investigación en Arquitectura, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.18861/ania.2024.14.1.3819

Abstract

In December 1961, Venezuela signed a technical cooperation agreement with the State of Israel in the context of its agrarian reform. As a result, a group of Israeli experts provided assistance for several years in a series of regional projects and in building local expertise in rural development. Their involvement helped Venezuela’s agrarian reform quickly gain momentum; however, it would be a mistake to believe that this achievement was solely due to the Israeli contribution. By highlighting the differences and continuities in some official policies concerning rural development in Venezuela before and after the passing of the Agrarian Reform Law of 1960, this paper will demonstrate that while Venezuelan democracy wanted to make a clean break from the past and promoted important structural changes that provided a greater degree of spatial and social justice in the countryside, there were also many continuity elements involving previous rural development policies. The technical expertise that made the agrarian reform possible, as well as the set of ideas and ideals that propelled its implementation, were built in part on a succession of previous experiences that paved the way for what was to come.

Keywords

Rural development; Rural planning; Colonization; Land reform; Venezuela

Resumen

En diciembre de 1961, Venezuela firmó un acuerdo de cooperación técnica con el Estado de Israel en el contexto de su reforma agraria. Como resultado, un grupo de expertos israelíes proporcionó asistencia durante varios años en una serie de proyectos regionales y en la creación de experticia local en desarrollo rural. Su participación ayudó a que la reforma agraria de Venezuela cobrara impulso rápidamente; sin embargo, sería un error creer que este logro se debió únicamente a la contribución israelí. Al poner de relieve las diferencias y continuidades de algunas políticas oficiales relativas al desarrollo rural en Venezuela antes y después de la aprobación de la Ley de Reforma Agraria de 1960, este documento demostrará que, si bien la democracia venezolana quiso romper con el pasado y promovió importantes cambios estructurales que proporcionaron un mayor grado de justicia espacial y social en el campo, también hubo muchos elementos de continuidad en las políticas de desarrollo rural anteriores. La experiencia técnica que hizo posible la reforma agraria, así como el conjunto de ideas e ideales que impulsaron su implementación, se construyeron en parte sobre una sucesión de experiencias previas que prepararon el camino para lo que vendría.

Palabras clave

Desarrollo rural; Planificación rural; Colonización; Reforma de la tierra; Venezuela

Resumo

Em dezembro de 1961, a Venezuela assinou um acordo de cooperação técnica com o Estado de Israel no contexto de sua reforma agrária. Como resultado, um grupo de especialistas israelenses prestou assistência por vários anos em uma série de projetos regionais e na construção de conhecimento local em desenvolvimento rural. Seu envolvimento ajudou a iniciativa de reforma agrária da Venezuela a ganhar impulso rapidamente; no entanto, seria um erro acreditar que essa conquista se deveu exclusivamente à contribuição israelense. Ao destacar as diferenças e as continuidades em algumas políticas oficiais relativas ao desenvolvimento rural na Venezuela antes e depois da aprovação da Lei de Reforma Agrária de 1960, este artigo demonstrará que, embora a democracia venezuelana quisesse romper com o passado e promover mudanças estruturais importantes que proporcionaram um maior grau de justiça espacial e social no campo, também havia muitos elementos de continuidade envolvendo políticas de desenvolvimento rural anteriores. O conhecimento técnico que possibilitou a reforma agrária, bem como o conjunto de ideias e ideais que impulsionaram sua implementação, foram construídos, em parte, com base em uma sucessão de experiências anteriores que prepararam o caminho para o que estava por vir.

Palavras-chave

Desenvolvimento rural; Planejamento rural; Colonização; Reforma agrária; Venezuela

This paper aims to highlight the differences and continuities in certain official policies for rural development in the Venezuelan countryside before and after the passing of the Agrarian Reform Law in 1960. This reform, promoted by the nascent Venezuelan democracy after the fall of the military dictatorship of Marcos Pérez Jiménez in 1958, aimed to eliminate the dominant latifundium system inherited from the colonial era and redistribute land among poor peasants, enabling their economic and social emancipation through the notion of the social function of property (Ley de Reforma Agraria, 1960). [Fig.1] President Rómulo Betancourt wanted the agrarian reform to benefit the greatest number of peasants as quickly and extensively as possible, as he considered the reform a debt that democracy owed its peasantry after previous attempts to democratize the agrarian structure were hindered by the dictator. However, the scale and speed of the enterprise soon proved to be a challenge, and much improvisation took place during the early years of agrarian reform (Machado, n.d.).

Figure 1.

President Rómulo Betancourt and former president Rómulo Gallegos at

the act of enactment of the Agrarian Reform Law in March 1960.

Source: Courtesy of Archivo Fotografía Urbana. Author of the photo is unknown.

Seeking methods and ideas to make the

agrarian reform more efficient but without compromising its pace, the

Venezuelan government signed a technical cooperation agreement with

the Division of International Cooperation (Mashav) of the Israeli

Ministry of Foreign Affairs in December 1961, at a time when Israel

was believed to be at the forefront of agricultural planning (Laufer,

1967; Klayman 1970; Eidt, 1975). A group of Israeli experts lived and

worked in Venezuela for many years, collaborating on a variety of

projects and developing local technical expertise aimed at

modernizing the countryside. They introduced Raanan Weitz’s concept

of Integrated Rural Development, an innovative model that ensured the

simultaneous planning of the physical, agroeconomic, and

socioeconomic dimensions of rural development on various scales,

which had recently been tested with great success in the Lakhish

region of Israel (Weitz, 1987). More importantly, and to make rural

development truly integrated, they helped consolidate a fragmented

body of experts coming from different ministries and with different

objectives into a coherent working group that would go on to

collaborate on comprehensive rural development projects.

This technical cooperation agreement helped Venezuela’s agrarian reform quickly gain momentum, become a model for other agrarian reforms in Latin America, and train an elite group of engineers, agronomists, sociologists, economists, zootechnicians and architects specializing in new forms of rural development. However, it would be a mistake to believe that this achievement was solely due to the ideas and methods contributed by the Israeli experts. Numerous experiences prior to that technical cooperation agreement, on subjects as varied as irrigation systems, the planning of new agricultural colonies, and the provision of rural housing, likely facilitated the introduction of new ideas and methods.

By highlighting the differences with the policies preceding the Agrarian Reform Law of 1960, this paper will show that the agrarian reform undoubtedly promoted important structural changes in the agrarian structure of the country, thus guaranteeing a greater degree of spatial equity for Venezuelan peasants. However, it will also demonstrate that while Venezuelan democracy wanted to make a clean break from the past, a critical reading of the history of rural development in Venezuela also shows many elements of continuity. The technical expertise that made the agrarian reform possible, as well as the set of ideas and ideals that propelled its implementation, were built in part on a succession of previous experiences that paved the way for what was to come. This critical perspective will help broaden architectural and urban discourse on the participation of architects and planners in the transformation of the Latin American countryside during the twentieth century.

When the Agrarian Reform Law was passed in 1960, the Instituto Agrario Nacional (IAN, the National Agrarian Institute) was designated as the agency in charge of transforming the agrarian structure and distributing agricultural land among Venezuela’s landless peasants. The IAN already existed, however, since it had been created in 1949 and had been promoting the planning of new agricultural settlements for more than a decade. In addition to IAN, other government agencies had also been working for many years to modernize the countryside, replacing traditional rural housing with modern structures and introducing modern irrigation systems. For this reason, it is perhaps important to recall the previous experiences of the Venezuelan State in planning rural settlements after the death of General Juan Vicente Gómez in 1936, as these experiences formed the foundation on which the new expertise in rural planning was built.

A brief review of these experiences will help identify some crucial differences between them and the efforts following the passage of the third Agrarian Reform Law of 1960, as well as important continuities. I will first refer to the colonies carried out by both the Instituto Técnico de Inmigración y Colonización (ITIC, the Technical Institute of Immigration and Colonization), created by Venezuelan President Eleazar López Contreras in 1938, and by the IAN during the dictatorship of Marcos Pérez Jiménez after taking over ITIC’s functions in 1949. Then, I will refer to the Rural Housing Program, launched in 1948 by the Ministerio de Sanidad y Asistencia Social (MSAS, the Venezuelan Ministry of Health and Social Assistance) in its battle against malaria and other tropical diseases.

The creation of the ITIC in 1938 was aimed at managing a land settlement program through the development of new agricultural colonies. However, as its name suggests, the program was directed toward immigrants rather than Venezuelan peasants. Moreover, the immigrants who would benefit from this program were carefully selected with more than just agricultural productivity in mind. As Miguel Tinker Salas and Susan Berglund recall, leading Venezuelan intellectuals of the time, such as Alberto Adriani, Mariano Picón Salas, and Arturo Uslar Pietri, among others, believed that it was necessary to improve the racial composition of the country by attracting white European immigrants (Berglund, 1980; Tinker Salas, 2009). Many of them collaborated with the governments of General Eleazar López Contreras (1935–1941) and General Isaías Medina Angarita (1941–1945). Uslar Pietri even went on to direct the ITIC in 1939. The institute was therefore more concerned with eugenics than with land reforms. In its view, the white foreign settler was essential to developing the countryside, while the local peasant was no more than a helper (MAC, 1959). According to a 1959 publication by the Ministerio de Agricultura y Cría (MAC, the Venezuelan Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock), reporting on agrarian colonization between 1830 and 1957, fifty Danish families, fifty-five Portuguese settlers, and many other European immigrants established themselves in more than a dozen colonies in the north of the country (MAC, 1959).

Mention of the design and physical planning of these settlements is nonexistent, since, as noted in the abovementioned publication, documentation of this period is scarce and tends to focus on productivity, costs, and the origins of the immigrants (MAC, 1959). However, it is known that starting in 1946, the Corporación Venezolana de Fomento (CVF, the Venezuelan Development Corporation) initiated a program of Comunidades Agrarias in collaboration with ITIC and MAC, but also with the Directorate of Hydraulic Works of the MOP when irrigation works were needed.

This program marked a major leap forward in the planning and design of new settlements on a regional scale, with the scope of the projects also taking a new direction. The irrigation system of El Cenizo, in the lower Motatán Valley of the State of Trujillo, is probably the most important of the fourteen settlements planned during this period—not only for being the first regional-scale project planned by a consortium of government agencies but also for incorporating local peasants into the scheme. This anticipated the political ambitions of Acción Democrática, the ruling political party during the three-year period known as the Trienio Adeco (19451948), for the agrarian reform that was on their agenda but had not yet been enacted (MAC, 1959; Texera Arnal, 2017).

Indeed, the first modern agrarian reform laws were passed in 1945 by the regime of General Medina Angarita, and in 1948 by the reformist government of President Rómulo Gallegos during the last months of the Trienio Adeco. However, neither was implemented because the two governments were overthrown shortly after their enactment (Betancourt, 1956). Both laws, however, were intended to eliminate the dominant latifundia system inherited from the colonial era and redistribute land among poor peasants to enable their economic and social emancipation. Both also established the creation of the IAN as the centralizing and organizing instrument for their implementation (Párraga García, 2001). Although the conservative military dictatorship installed after the 1948 coup overturned the law enacted by Acción Democrática, it established the so-called Agrarian Statute of 1949 and finally created the IAN (Schuster F., 1972; Eidt, 1975).

The irrigation works being carried out by the MOP in El Cenizo were already quite advanced when the Pérez Jiménez dictatorship took over. The development of the project continued under his government, albeit with significant modifications to the criteria of the original scheme. Primarily, the progressive comunidad agraria that was to benefit a large number of local peasants was now transformed into a conservative colony for twenty-seven agricultural experts—forty percent of which were foreign settlers—and the small plots intended for peasants were consolidated into large estates of one hundred hectares each to facilitate mechanized farming. [Fig.2] In this new context, a dispersed settlement pattern was preferred, in contrast to ITIC’s earlier attempts to separate agricultural plots from housing and concentrate families in village-like settlements. Because of a recent experience with a concentrated settlement, which had caused disputes among settlers due to the proximity between plots (Eidt, 1975), houses were now built on each parcel, in clusters of four, at the cadastral boundary crossings. Each cluster would share a warehouse for machinery, and the collective services would be concentrated in the central settlement (MAC, 1959).

Figure 2. Immigrant farmer driving a tractor in a field.

Source: Courtesy of Archivo Fotografía Urbana. Author of the photo is unknown.

The agricultural colony of Turén, built by

the dictatorship in the State of Portuguesa and the most famous of

IAN’s undertakings between 1949 and 1958, followed the same

criteria applied to the irrigation system of El Cenizo. This

confirmed that the dictatorship had no intention of benefiting local

peasants. It had other plans in mind that were more aligned with the

former ITIC’s belief in white settlers as agents of modernization.

The difference between the two projects would lie in the scale of

this new endeavor, never before seen in the country and exceptional

even by global standards, to the point that in a 1952 conference

paper presented by George W. Hill and Gregorio Beltrán, the authors

stated that in the span of merely two years, Turén had developed

‘into one of the outstanding planned agricultural communities of

the hemisphere’ (Hill & Beltrán, 1952). It became an important

flagship project of the dictatorship and was used as official

propaganda in Venezuela and abroad to legitimize the authoritarian

government with actions (Blackmore, 2008).

While twenty-seven families had been established in El Cenizo, more than seven hundred settlers moved to the colony of Turén in less than ten years (MAC, 1959). The ratio of foreign white colonists to Venezuelan peasants would resemble that of El Cenizo, albeit on a much larger scale than previous projects and with a discriminatory disparity in plot size that privileged European settlers—mostly Italians, but also Spaniards and Germans. [Fig.3] IAN defined two types of parcels: macro-parcelas, ranging from thirty to fifty hectares and regularly shaped to facilitate mechanized agriculture; and micro-parcelas of five hectares each for conucos, a Venezuelan term for small plots of cultivated land, generally used for subsistence farming. Nearly three hundred of the 728 settlers were foreigners, and almost all of them were given macro-parcelas. In addition, although some two hundred Venezuelans were also given similarly sized plots, almost all the micro-parcelas were given to local peasants (Hill & Beltrán, 1952; MAC, 1959). As stated in the 1957 MAC report, the rationale for this policy was to establish larger estates as models of a modern farm: “schools” where white European settlers would educate the local peasants holding micro-parcelas by example. Only when they acquired the modern techniques enabling efficient cultivation could they have a macro-parcela of their own (MAC, 1959). [Fig.4] This conception of the local peasant as a passive pupil without valuable knowledge of local conditions echoed that of the ITIC in the Danish colony of Chirgua.

Figure 3:

Parade of tractors driven by the children of immigrant

settlers in the agricultural colony of Turén.

Source: Courtesy of Archivo Fotografía Urbana. Author of the photo is unknown.

Figure

4: Venezuelan peasants picking a peanut harvest.

Source: Courtesy of Archivo Fotografía Urbana. Photo by Valenting Betegh.

The same dispersed settlement pattern was

also employed in Turén, locating housing units within the cultivated

area and clustering them in groups of four at road crossings (Eidt,

1975). As Jacob O. Maos argues, this settlement pattern prioritizes

agricultural production over any other variable, as it reduces the

farmer’s travel time to the fields and lowers transportation costs

at the expense of hindering the provision of services and

infrastructure and making institution building and cooperation among

farmers more difficult (Maos, 1984). In Turén, where the distance

between housing clusters was almost one kilometer in areas with

macro-parcelas

and 255 meters in those with micro-parcelas,

these observations are clearly valid.1

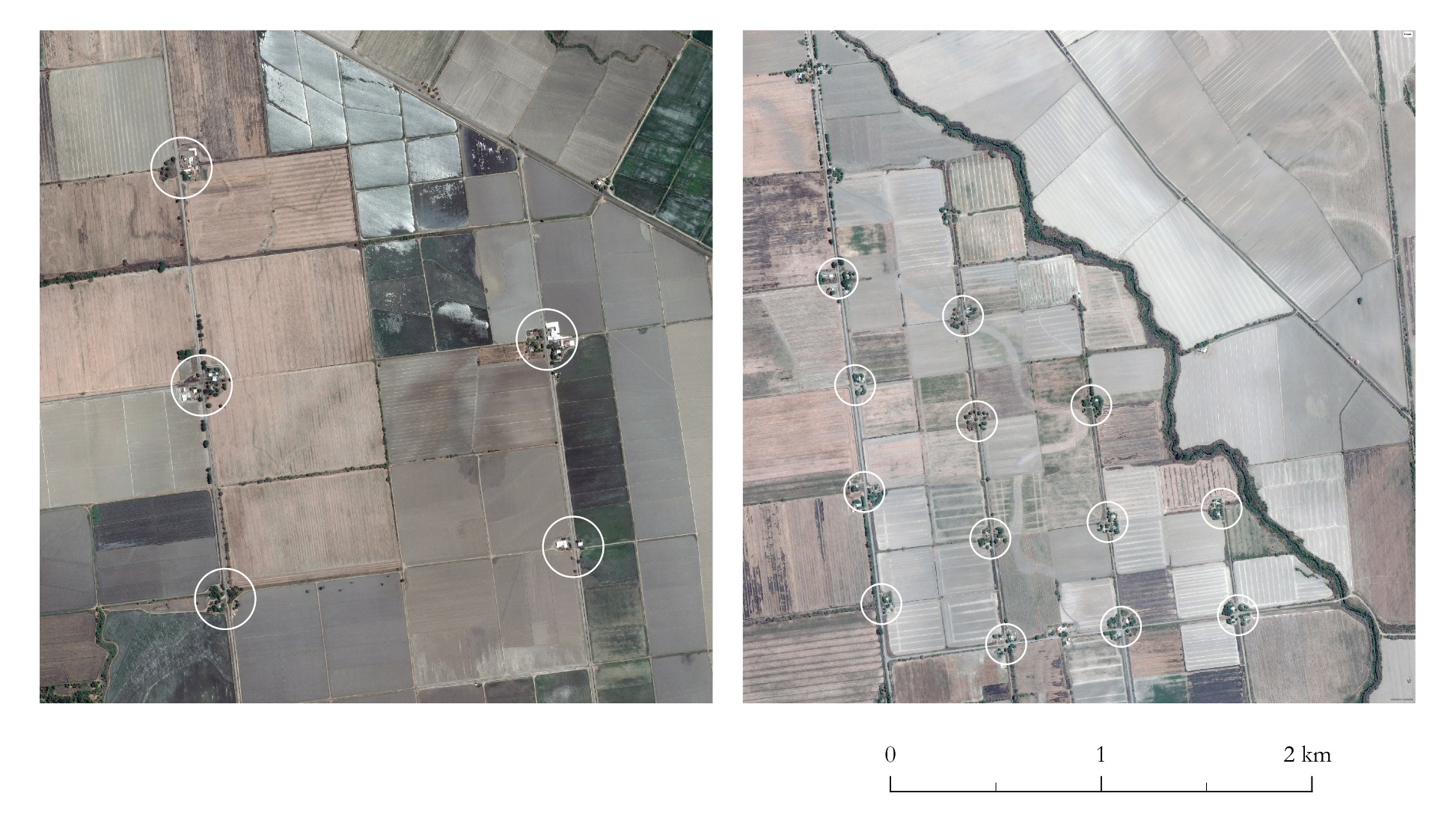

[Fig.5]

Figure

5: Scale comparison between

macro-parcelas and micro-parcelas in the agricultural colony of

Turén.

Source: made by the author.

Outside of those enclaves where foreign settlers were favored by governments promoting racist policies or miscegenation at best, Venezuela’s rural areas were being decimated by severe and periodic epidemics of tropical diseases, forcing their inhabitants to move to the country’s cities and oil fields well into the 1940s. To contribute to the eradication of malaria and prevent further abandonment of rural areas, the Malariology Division of the MSAS created the Rural Housing Office. From 1948 onwards, it began to develop expertise in the design and construction of modern dwellings in rural areas, with the goal of creating healthier domestic spaces for peasant families. These preliminary efforts became official policy in March 1958, when the Programa Nacional de Vivienda Rural (PNVR, the National Rural Housing Program) was created by decree and the Rural Housing Office, which until that point had been managing with scarce resources, was consolidated into the Rural Housing Division (RHD) (Decreto Nro. 84, 1958; Pedregal, 1971). Architects like Domenico Filippone (initially) and later Herminio Pedregal, Haydée Machado, Alfredo Sutil, and José Leonardo Yánez, among others, worked in the RHD developing hygienic rural housing solutions that sometimes amounted to completely new hamlets.2 The rural housing program was under the management of the Ministry of Health, as scientists and technicians thought the health crisis stemmed from traditional building techniques. They saw traditional dwellings as a source of insalubrity and misery, basing their premises on several assumptions that were echoed by official propaganda (Contreras et al., 2015).

The architects of the RHD were thus tasked with civilizing this so-called backward peasantry, and the war they were helping to wage against malaria soon became a battle against traditional architecture. [Fig.6] Domenico Filippone was an Italian architect who emigrated to Venezuela in 1946 after being invited by the Rockefeller Foundation due to his experience in the eradication of malaria in the context of the colonization of the Pontine Marshes (Ragone, 2015). Filippone, who also coordinated the RHD and the PNVR for several years (Calvo Albizu, 2018), writes in the first pages of a 1957 book entitled Vivienda Sana (Healthy Housing), [Fig.7] coauthored with colleagues of the Malariology Division, about the need to eliminate the differences between the citizen and the peasant:

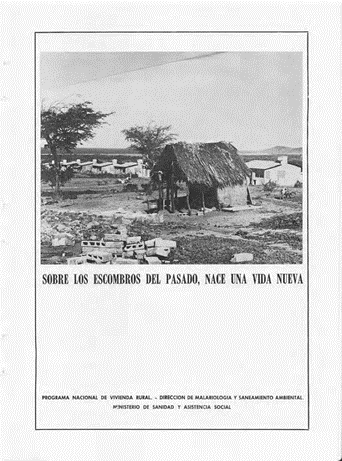

Figure 6:

State propaganda promoting the work of the Rural Housing Division,

stating that “on the rubble of the past, a new life is born”

Source: Punto 19 (August-September 1964), 49.

Figure

7: Cover of the second edition of

Vivienda Sana.

Source: Malariology Division, 1987.

In

the last few years, it has begun to be considered, although in truth

only by certain reforming spirits, the necessity of extending to the

farmer and his family the benefits of progress achieved in the

cities. As a result of this initiative, the new technique of Ruralism

has recently been studied. In this technique, the man of the country

is considered on the same level as the man of the city, not only from

the juridical, social and educational point of view, but also from

that of the various material needs of life. (Malariology Division,

1957: 2. Translated by the author)

The same introductory pages expressed the belief that replacing traditional houses with modern and hygienic ones would increase agricultural productivity due to the material and spiritual improvements of the peasant population. This effort to modernize hinterland housing would replace earth floors with easy-to-wash soil cement floors; thatched roofs with a layer of soil cement waterproofed with asphalt to prevent insect and rodent nests; rammed earth, wattle and daub, or adobe walls with compressed earth blocks stabilized with cement that were better able to withstand the elements; and latrines with toilets. Not without value judgments, the authors are convinced that this housing modernization would make rural house peasants willing to stay at home—as opposed to that vicious cycle of evasion that men seem so prone to, where the repulsiveness of their current living condition pushes them to the bar and therefore to alcoholism. According to Filippone and his co-authors, the issue of sanitary standards in the countryside was an educational problem. Seen from this point of view, the architects of the RHD are the schoolteachers and the peasants their uncivilized pupils, while the rural house becomes a technical artifact with pedagogical qualities.

Regardless of the significant shortcomings of such a large-scale program—the repetition of hundreds of seemingly identical housing units throughout the country, the loss of traditional construction techniques, or the imposition of typologies that failed to account for established living practices, such as cooking outdoors or the use of hammocks—the efforts made by the RHD proved to be quite successful from a sanitary perspective, considering that 68% of the malaria-affected territory was declared malaria-free by the World Health Organization by 1959 (Griffing et al., 2014). Thanks to this status, the architects of the RHD earned a reputation as efficient agents of modernization in rural areas. It should come as no surprise then that when the Agrarian Reform Law was passed in 1960, the government invited them to collaborate with the National Agrarian Institute in the territorial project of modernizing the countryside.

The information presented in this article enables us to discern certain differences between the rural development policies that preceded the approval of the Agrarian Reform Law in 1960 and what followed. First, it is clear that despite the ITIC (1938–1949) and the IAN during the dictatorship of Marcos Pérez Jiménez (1949–1958) having two decades of combined experience in planning new agricultural settlements and increasing productivity by creating conditions for mechanized agriculture, after 1958, the Venezuelan democracy considered it advisable to distance itself from the works of previous governments, particularly after the approval of the Agrarian Reform Law in 1960. The favoritism toward foreigners that characterized rural development during previous governments was not only a policy that ran counter to the objectives of agrarian reform, which was focused on the democratization of land ownership and the empowerment of poor peasants, it also created a strong sense of resentment that could become a spark for a communist threat. This was precisely what the United States was trying to prevent by promoting agrarian reforms in Latin America and the Caribbean through the Alliance for Progress foreign aid program that was launched in 1961, in the context of the Cold War and following the success of the Cuban Revolution (Latham, 1998).

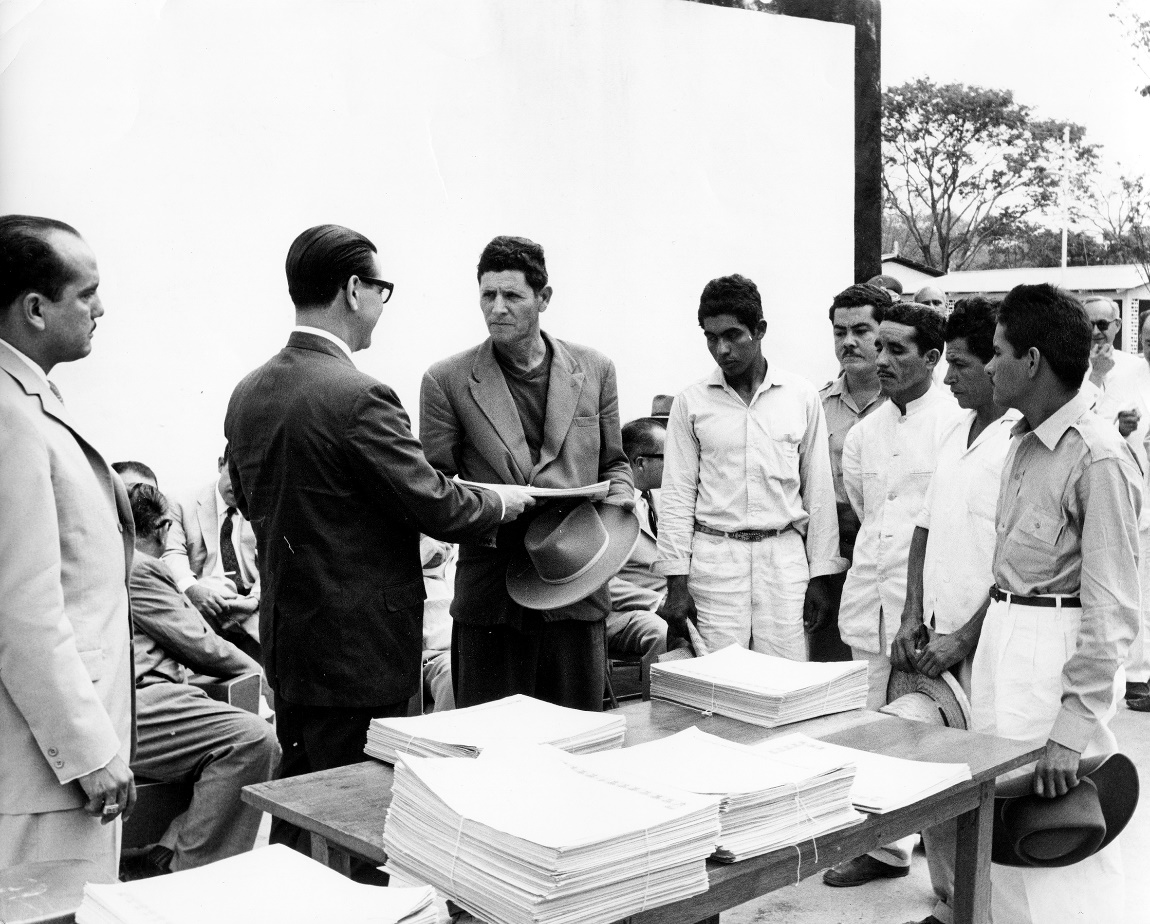

Moreover, the newly installed democratic government believed that the rural population required attention after decades of neglect by the state. This was not solely due to paternalism, but because Acción Democrática, the dominant democratic party, had been promoting the politicization of the Venezuelan peasantry since 1945 to gain their support, especially after the creation of the Federación Campesina de Venezuela (FCV, the national peasant union) in 1947. The new policies would revive old ideas that were previously circulating during the Trienio Adeco and were soon abandoned by the dictatorship, such as a true agrarian reform to redistribute land among the peasantry to enable their social and economic emancipation. In this context, the IAN would assume a new role and rural development policies would take a radical turn from the previous ones. In addition, a significant share of oil revenues was earmarked for investment in the countryside to improve the living standards of Venezuelan peasants. This was undoubtedly a significant project of spatial and social justice. [Fig.8]

Figure

8: Handing over of agrarian reform

titles to Venezuelan peasants and producers by the government of

Rómulo Betancourt around 1963.

Source: Courtesy of Archivo Fotografía Urbana. Author of the photo is unknown.

Despite the substantial differences between

the rural policies of previous governments and those of democracy,

there are also important continuities. The first thing worth

highlighting is the work of the RHD and the PNVR it coordinated. Even

if the architects of the RHD were not involved in planning new

settlements, replacing traditional dwellings with modern housing

types, usually on demand, often resulted in clusters of multiple

units, constituting a kind of hamlet. This accumulated experience in

working with rural communities—and the success of the PNVR in the

eradication of malaria, along with the recognition it brought the

country—created the conditions for a unique pairing of agrarian

reform policies and the extensive provision of rural housing. Beyond

questions of technical expertise, and more in line with the

ideological nature of modernization, the government also continued to

see peasants as a population requiring education, making the state’s

project of democratizing the countryside also a civilizing one.

Another important continuity worth noting is the precedent that sheds light on the ease with which different government agencies collaborated on large-scale projects. In the context of agrarian reform, this became apparent after the team of Israeli experts arrived in Venezuela and introduced the notion of Integrated Rural Development. Indeed, the cooperation promoted and coordinated by the Corporación Venezolana de Fomento with ITIC, MAC, and MOP for the development of the so-called comunidades agrarias during the Trienio Adeco (1945–1948), bears a striking resemblance to the inter-ministerial cooperation that would be promoted by the Israelis in 1963 with the help of the Venezuelan Central Office of Coordination and Planning (CORDIPLAN), which incorporated the IAN, the Agricultural and Livestock Bank (BAP), MOP, MAC, and the RHD of the MSAS. Although both are top-down, centralized collaborations strictly framed within the confines of the public sector, they exhibit uncommon flexibility and political will, reflecting the enthusiasm that prevailed during the early years of democratic rule.

Finally, the idea that colonization was the appropriate path also endured. As Cristóbal Kay observes, three-quarters of the land affected by the Venezuelan agrarian reform was already owned by the state (Kay, 1998). This means that, although the Agrarian Reform Law allowed the state to expropriate private agricultural land that did not comply with the principle of the social function of property, it preferred to build new agricultural settlements on uncultivated state-owned land rather than redistribute private land. In other words, while Venezuelan peasants were now the only privileged recipients of agrarian reform, the policy of colonizing the countryside and establishing new human settlements prevailed.

These continuities demonstrate that, although Venezuelan democracy preferred to make a clean break from the past, its agrarian reform benefited greatly from past experience, despite its shortcomings. It could also be argued that the Israeli experts who came to assist in Venezuelan agrarian reform would have had a much more difficult time building local expertise from scratch had they not found a team of capable professionals already in place. Integrating technicians from different government agencies would have been more difficult in the absence of previous experiences of inter-ministerial cooperation. Furthermore, their ideas on rural development, based on their experience in the colonization of Israel, might have been challenged without local experience in the colonization of rural areas. Consequently, the remarkable progress achieved during their relatively short time in Venezuela would have been unlikely if these continuities had not existed.

Nevertheless, the participation of architects and planners in the transformation of rural areas remains a largely overlooked chapter of Venezuelan history that deserves greater attention. Given the lack of access to information and official archives related to Venezuela, there is ample room for scholars interested in advancing new research on these issues. Specifically, there is a need to explore how architects and urban planners in general contributed to realizing the state’s objectives of organizing, integrating, and enhancing the productivity of the countryside within the framework of its modernizing and nation-building project.

The author would like to thank the entire team of Archivo Fotografía Urbana for their generosity in sharing the invaluable material they preserve. He is also grateful to the Gerda Henkel Stiftung, which supported this research.

Article

final approval

MA. Arch. Andrea Castro Marcucci, Editor in chief, and PhD Fabio Capra Ribeiro, Guest Editor, approved the f inal version of this article.

Author

contribution

MSc. Arch. Ricardo Avellais responsible for the entire preparation of the article.

Berglund, S. (1980). The "Musiues" in Venezuela: immigration goals and reality, 1936-1961 [Doctoral dissertation, University of Massachusetts Amherst]. https://doi.org/10.7275/jxx1-h426

Betancourt, R. (1956). Venezuela, Política y Petróleo. Editorial Senderos.

Blackmore, L. (2017). Spectacular Modernity: Dictatorship, Space, and Visuality in Venezuela, 1948-1958. University of Pittsburgh Press.

Calvo Albizu, A. (2018, December 9). ¿SABÍA USTED… que en 1958, hace ya 60 años, se termina la construcción de la Casa de Italia en Caracas? Fundación Arquitectura y Ciudad. https://fundaayc.wordpress.com/2018/12/09/sabia-usted-32/

Contreras, W., Owen de Contreras, M. & Contreras Owen, A.A. (2015). La vivienda rural venezolana en la dimensión de la sostenibilidad. Laboratorio de Sostenibilidad y Ecodiseño UPV-ULA, Centro de Investigación de la Vivienda y el Hábitat. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305489168_La_Vivienda_Rural_Venezolana_en_la_Dimension_de_la_Sostenibilidad

Decreto Nro. 84 (Se establece un Programa Nacional de la Vivienda Rural). Gaceta oficial de la República de Venezuela N.º 25.610 (1958, March 14).

División de Malariología (1957). Vivienda Sana. División de Malariología del Ministerio de Sanidad y Asistencia Social.

Eidt, R.C. (1975). Agrarian Reform and the Growth of New Rural Settlements in Venezuela. Erdkunde 29(2), 188133. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25641613

Griffing, S.M., Villegas, L., & Udhayakumar, V. (2014). Malaria Control and Elimination, Venezuela, 1800s–1970s. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 20(10), 16911696. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2010.130917

Hill, G.W. & Beltrán, G. (1952, February 19). Land Settlement in Venezuela: With Especial Reference to the Turén Project. [Conference presentation]. Second Annual Conference of the Asociación Venezolana Para el Avance de la Ciencia, Caracas, Venezuela.

Kay, C. (1998). Latin America’s Agrarian Reform: Lights and Shadows. Land Reform, Settlement and Cooperatives 2: 8–31.

Klayman, M.I. (1970). The Moshav in Israel: a Case Study of Institution-Building for Agricultural Development. Praeger Publishers.

Latham, M.E. (1998). Ideology, Social Science, and Destiny: Modernization and the Kennedy-Era Alliance for Progress. Diplomatic History 22(2): 199–229. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24913658

Laufer, L. (1967). Israel and the Developing Countries: New Approaches to Cooperation. Twentieth Century Fund.

Ley de Reforma Agraria, Gaceta oficial de la República de Venezuela N.º 611 extraordinario (1960, March 19).

MAC (1959). La colonización agraria en Venezuela: 1830–1957. Dirección de Planificación Agropecuaria del Ministerio de Agricultura y Cría.

Machado, Planificación de comunidades rurales (unpublished typewritten manuscript) private property of Ernestina Fuenmayor.

Maos, J.O. (1984). The Spatial Organization of New Land Settlement in Latin America. Westview Press.

Párraga García, G. (2001). Arrendamiento de Tierras y Legislación Agraria en Venezuela Durante el Período 1941–1948. Saber 13(1):74–81. http://saber.udo.edu.ve/index.php/saber/article/view/673

Pedregal, H. (1971). Plan de investigación BANAP-SAS (Tomo 1). Banco Nacional de Ahorro y Préstamo y Ministerio de Sanidad y Asistencia Social.

Ragone, V.P. (2015). Italia en Caracas: proyecto de conservación, restauración y puesta en valor de la Casa de Italia [Unpublished Master’s Thesis, Universidad Central de Venezuela]. https://www.academia.edu/65718105/ITALIA_EN_CARACAS

Schuster F., J.F. (1972). Rural Problem-Solving Policies in Venezuela, With Special Reference to the Agrarian Issue. Land Tenure Center, University of Wisconsin-Madison. https://minds.wisconsin.edu/handle/1793/56709

Texera Arnal, Y. (2017). El riego agrícola en Venezuela en archivos de la Dirección de Obras Hidráulicas del Ministerio de Obras Públicas (1936-1960). Revista Geográfica Venezolana 58(1), 184–197. http://erevistas.saber.ula.ve/index.php/regeoven/article/view/11293

Tinker Salas, M. (2009). The Enduring Legacy: Oil, Culture, and Society in Venezuela. Duke University Press.

Weitz, R. (1987). “Rural Development: the Rehovot Approach.” Geoforum 18(1), 21–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7185(87)90018-2

1 All the economic, social, and municipal facilities would be located in the new settlement of Turén, some ten kilometers south of Villa Bruzual.

2 It should be noted that in 1960, the Malariology Division and the Sanitary Engineering Division merged and became the Directorate of Malariology and Environmental Sanitation, which continued to manage the PNVR.