Towards a Sustainable Future: Present and Future Energy Policy Assessment for Residential Envelopes in Mexico

Hacia un futuro sostenible: Evaluación presente y futura de políticas energéticas para envolventes residenciales en México

Rumo a um futuro sustentável: avaliação da política energética atual e futura para envelopes residenciais no México

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.18861/ania.2025.15.2.4159

Claudia

Eréndira Vázquez Torres

Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán

México

claudia.vazquez@correo.uady.mx

ORCID:

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5388-0780

Gabriel Hernández Pérez

Universidad

Autónoma de Yucatán

México

jose.hernande@correo.uady.mx

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7709-5760

Recibido:

07/05/2025

Aceptado: 15/10/2025

Cómo citar:

Vázquez-Torres,

C. E., & Hernández Pérez, G. (2025). Hacia un futuro

sostenible: Evaluación presente y futura de políticas energéticas

para envolventes residenciales en México. Anales

de Investigación en Arquitectura,

15(2).

https://doi.org/10.18861/ania.2025.15.2.4159

Abstract

Latin American countries implement regulations to improve energy efficiency in housing in the face of climate change. The objective of this study was to evaluate the thermal performance and mandatory policies for energy efficiency in buildings in Mexico throughout the 21st century. This study developed a methodology with indicators of climate change mitigation and thermal comfort, applied to social housing. A numerical analysis was conducted considering two envelope improvement scenarios and their projections for 2024, 2050 and 2100. The results indicate a reduction of about 4 °C in the operative temperature by improving the envelope compared to the reference case. The proposed methodology represents a tool to evaluate energy policies and anticipate their effectiveness in the short, medium and long term, facilitating the design of new and used housing, as well as the implementation of strategies for a sustainable and equitable future.

Keywords: Climate change mitigation, developing countries, energy prospects, housing policy, social housing.

Resumen

Los países latinoamericanos implementan regulaciones para mejorar la eficiencia energética en viviendas frente al cambio climático. El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar el desempeño térmico y las políticas obligatorias para la eficiencia energética en edificaciones en México a lo largo del siglo XXI. Este estudio desarrolló una metodología con indicadores de mitigación del cambio climático y confort térmico, aplicados a viviendas de interés social. Se realizó un análisis numérico considerando dos escenarios de mejora de la envolvente y sus proyecciones para 2024, 2050 y 2100. Los resultados indican una reducción cercana a 4 °C en la temperatura operativa al mejorar la envolvente en comparación con el caso de referencia. La metodología propuesta representa una herramienta para evaluar políticas energéticas y anticipar su efectividad a corto, medio y largo plazo, facilitando el diseño de viviendas nuevas y usadas, así como la implementación de estrategias para un futuro sostenible y equitativo.

Palabras clave: Mitigación al cambio climático, países en desarrollo, prospectivas energéticas, política habitacional, vivienda social.

Resumo

Os países da América Latina implementam regulamentos para melhorar a eficiência energética nas habitações face às alterações climáticas. O objetivo deste estudo foi avaliar o desempenho térmico e as políticas obrigatórias para a eficiência energética em edifícios no México ao longo do século XXI. Este estudo desenvolveu uma metodologia com indicadores de mitigação das alterações climáticas e de conforto térmico, aplicada à habitação social. Foi realizada uma análise numérica considerando dois cenários de melhoria da envolvente e as suas projecções para 2024, 2050 e 2100. Os resultados indicam uma redução de cerca de 4 °C na temperatura de funcionamento através da melhoria da envolvente em comparação com o cenário de referência. A metodologia proposta representa uma ferramenta para avaliar as políticas energéticas e antecipar a sua eficácia a curto, médio e longo prazo, facilitando a conceção de habitações novas e usadas, bem como a implementação de estratégias para um futuro sustentável e equitativo.

Introduction

The energy sector is central to this approach due to its reliance on fossil fuels and its contribution to climate change-related issues like anthropogenic heat (Alhazmi et al., 2022; Bai et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2023). Energy policies now focus on sustainably reducing pollution, driven by the impact of energy use and the need for fair mitigation measures. Growing attention to energy poverty underscores the importance of inclusive, sustainable energy transitions (Fabbri et al., 2021; Jiglau et al., 2023; Littlewood et al., 2017). 70 % of the countries have implemented policies focused on energy end-use (Chévez et al., 2019), in some cases, incentives are promoted to favour the most disadvantaged. However, these measures need periodic reviews and actions to ensure long-term results (Cadaval et al., 2022). In this sense, energy policy research could contribute to the climate change mitigation agenda without inhibiting the most disadvantaged (Belaïd, 2022).

Future societal transformation depends largely on energy policies and resource optimisation amid climate change, with the chosen transition path shaping national energy use and its broader impacts (Gatto, 2022). Therefore, low-cost, efficient outcomes (Alford-Jones, 2022) that increase social equity are sought globally, especially in developing countries. The COVID-19 pandemic has caused the emergence of policies that facilitate obtaining fiscal stimuli. These stimuli are often considered "green" since they reduce polluting emissions (Andrew et al., 2022). High-income countries lead in energy efficiency policies, while nations like Chile and Mexico rely more on fossil fuels, raising CO₂ emissions (Jonek-Kowalska, 2022). The American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) is a key international promoter of energy efficiency standards for low-rise residential buildings, covering Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning (HVAC), energy use, and envelope airtightness ANSI/ASHRAE/IES 90.2 (2018).

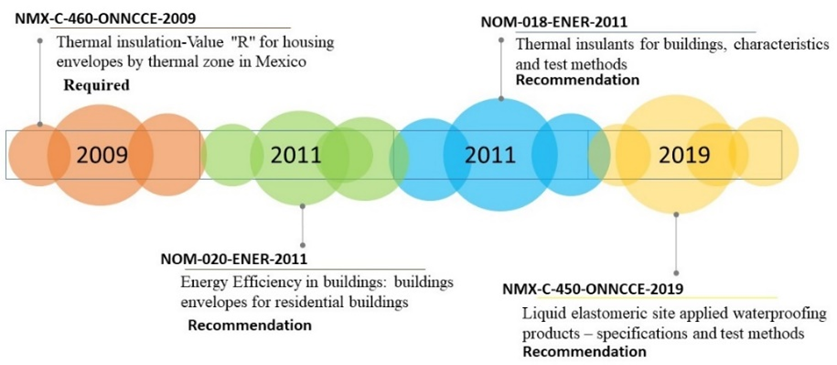

In Mexico, The Secretary of Energy (SENER by its Spanish acronym) promotes efficient electricity use, as building climate control accounts for over 40% of national consumption; energy-saving strategies aim to reduce residential use by up to 70% by 2027 (Secretaría de Energía, 2013). Figure 1 shows the current standards in Mexico related to the energy efficiency of residential building envelopes. The next figure indicates which regulations refer to a mandatory requirement and which refer to a recommendation.

Figure

1

Mexican

standards for building envelopes in social housing

According

to The National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI by its

Spanish acronym) Mexico (2022), the

number of dwellings in Mexico grew by 60% between 2000 and 2020,

increasing energy demand for user comfort. In response, The

National Workers' Housing Fund Institute (INFONAVIT by its Spanish

acronym) developed a green mortgage programme to assess technologies

and ecological features across climate zones. Within this framework,

NOM-020-ENER-2011

(2011) was issued to improve housing thermal performance, though its

methodology presents limitations for warm climates (Martín-Domínguez

et al., 2017), restricting its effectiveness mainly to temperate

zones, as noted by Alpuche Cruz et al. (2017). Additionally,

NMX-C-460-ONNCCE-2009 (2009) defines thermal inputs through the

envelope using R-values, linking cooling loads to the dwelling's

location within established thermal zones.

The 2020 green housing manual prepared by INFONAVIT included thermal insulation as a mandatory measure, taking NMX-C-460-ONNCCE-2009 as a reference. The monthly savings from the roof thermal insulation ecotechnology amount to MXN $360 in warm climates and MXN $134 in temperate climates for households in the highest income segment, defined by the programme as “7.40 UMAM and above”, where one Monthly Unit of Measurement and Update (UMAM) is equivalent to MXN $3,439.46 in 2025. Medrano-Gómez et al. (2017) analysed two case studies with a warm sub-humid climate and determined a 47% reduction in electricity consumption, applying NMX-C-460-ONNCCE-2009. Vázquez-Torres et al. (2022) concurred with the findings that achieved a reduced operative temperature of up to 7 °C in a case study with a temperate climate. Griego et al. (2012) analysed different energy efficiency measures in a temperate climate, which included increased envelope airtightness to achieve 52% annual energy savings. The findings to date raise the uncertainty of whether the reductions in heat gains achieved in the current scenario will prevail throughout the 21st century and whether the construction systems used to build the dwellings of the most vulnerable population can comply with current energy policies.

The principle of this study was to analyse, in the current scenario, a benchmark case with different building systems used regularly in Mexico, especially in mass housing for vulnerable users. Secondly, to evaluate compliance with mandatory energy efficiency standards and to compare the thermal performance of the proposed models throughout the 21st century, considering the impacts of climate change. The objective of this study was to obtain quantitative data on the application of the selected Mexican standards and the energy performance with the commonly used building systems in housing and to compare the current with future scenarios, which will provide the responsible actors with scientific information to make proactive and timely decisions regarding the future of the residential sector faced with climate change.

There are no precedents for the analysis of energy policies throughout the century for developing countries in the existing literature, so the main contribution of this study is to show the performance of the current energy policies in Mexico, as well as their future projections to direct them towards quantifiable and practical savings in the construction sector, which can be extended to other sectors of society and other regions. The aim was to reduce the need for more information on the effectiveness of existing regulations in housing to reduce energy poverty and contribute to social equality.

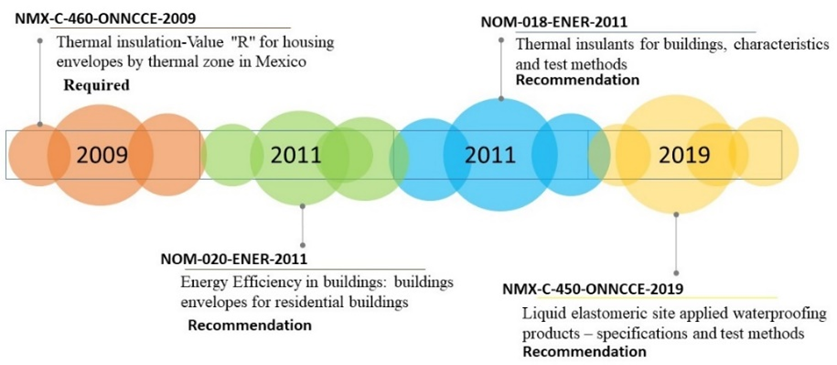

The scheme presented in Figure 2, divided into 5 sections, was proposed to achieve the objective. The mandatory regulations for building envelopes in Mexico and experimental monitoring process with a real case in the second section. Identification of future scenarios covering the 21st century considering the models developed by the Intergovernmental

Panel on Climate Change in third section. As a result, the analysis of future projections is projected to establish strategies to mitigate climate change that consider current regulations in developing countries.

Figure

2

Study

methodology flowchart. Based

on: (Diario Oficial de la Federación, 2009; Google data, 2020)

The study locality, León Guanajuato, México, is a city with almost two millioninhabitants (INEGI, Instituto Nacional de Geografía, 2023). According to the climate classification developed by Köppen (2020), it has the characteristics of a BSh climate, with annual averages of 19.3 °C for temperature and 57% for relative humidity (Sistema Meteorológico Nacional, 2020). The city is a major national and international commercial hub, largely due to its footwear industry. According to the National Housing (2022), Mexico has more than 35 million dwellings, 50% of which are in central regions of the country with a climate like that of the reference case.

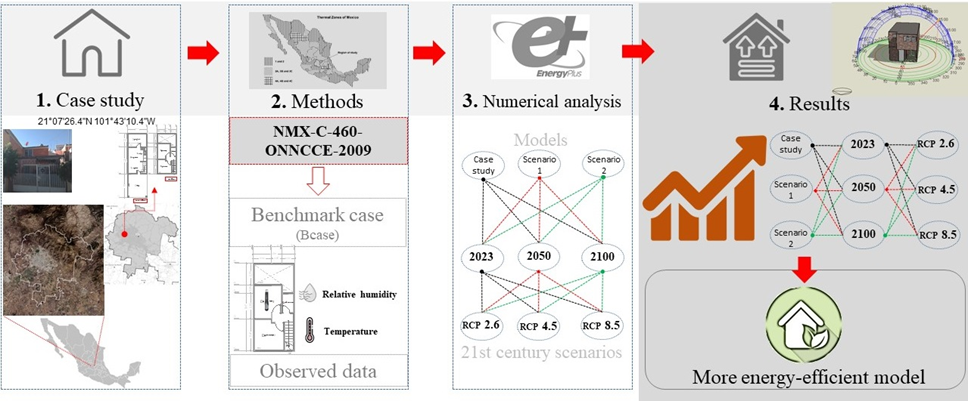

The most common construction systems in Mexico use brick, block, or cement for walls, and concrete slabs or joist-and-vault ceilings. In over 90% of such dwellings, no treatments are applied to the envelope, such as airtightness measures or thermal and acoustic insulation (Encuesta Nacional de Vivienda, 2021). For the working class, the most widespread housing typology is smaller than 60 m² and provides only the minimum regulatory spaces. These characteristics match those of the Bcase, which was built with extruded block walls, thick 3 mm glasses in windows and a concrete slab. Figure 3 shows the location of the Elitech RC-51H monitoring device used in the validation process.

Housing for socially and economically vulnerable groups is generally inhabited by working-class families whose members work between 8 h and 12 h per day; therefore, occupancy and activity schedules are concentrated during resting hours. The monitoring period was conducted in Bedroom 1, with measurements taken at the centre of the space in accordance with ASHRAE Standard 55 (American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, 2021). Measurements were recorded at three different heights: 0, 1.1, and 2.3 m.

Figure

3

Floor

distribution of the Bcase

The

monitoring campaign ran from June to September 2022, covering the

season with the highest cooling demand of the year. Prior to this, a

performance test of the data loggers was conducted, which showed an

accuracy range of less than 0.05 °C between devices, in line with

the requirements of ISO 7726:2001 (European Committee for

Standardization, 2001). The baseline system displayed poor control of

internal heat transfer. The observations at the three heights

evidenced the effects of heat transfer and air stratification. For

validation purposes, the results at 1.1 m were used, as this height

represents the geometric centre across all three axes.

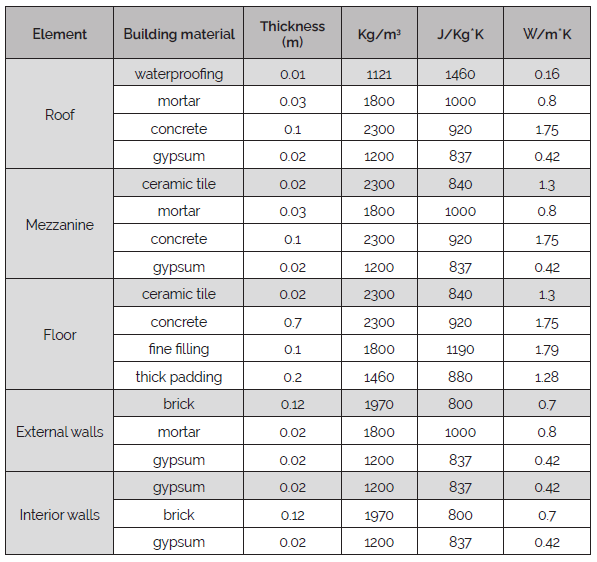

Table 1 shows the building systems of the Bcase with data such as thickness and thermal properties. It should be noted that these data were used in the numerical process described in section 2.3 below.

Table

1

Thermal

properties of the layers used in the Bcase.

Source: Cengel & Ghajar (2015)

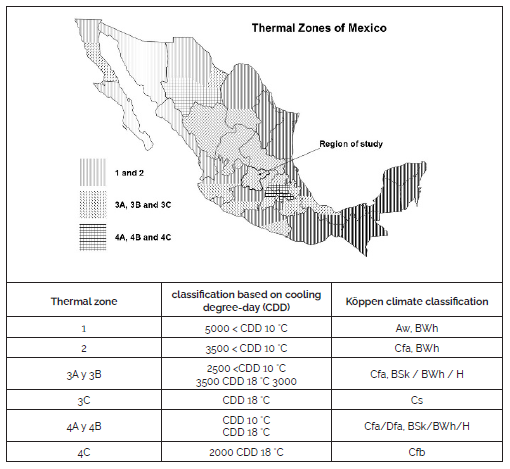

Sustainability strategies have recently promoted energy-saving measures in all sectors, including the residential sector, and efforts to ensure their implementation. Mexico implemented NMX-C-460-ONNCCE-2009 (2009) with the participation of authorities, housing developers, and the public to contribute to energy savings in residential refrigeration. The country was divided into climatic zones to characterise the requirements that the envelope must meet according to the climate where they are developed and to determine the total thermal resistance, or "R" value, according to the location and purpose of the insulation, which can be a) minimum; b) to achieve habitability, and c) to save energy. The thermal zones presented in Table 2 correspond to an adaptation of the Köppen climate classification based on Degree-Days.

Table

2

Classification

by thermal zone

As a result, weights were obtained to analyse energy efficiency in the residential sector. The scope of the NMX is to achieve habitability and energy savings according to each thermal zone. According to the NMX thermal classification, the Bcase is in zone 3A, with a temperate climate, characterised by an average temperature in the coldest month of less than 18 °C and a minimum R-value of 1.4 m² K/W and energy savings considered when reaching 2.8 m² K/W. According to NMX-C-460-ONNCCE-2009, in temperate climates, it is mandatory to comply with the thermal resistance of the roof slab, while in warm climates, the thermal resistance of the wall with the most sunlight must be added.

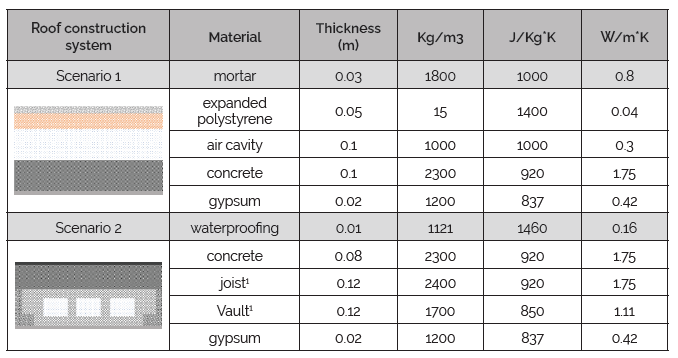

The simulation compared the roof slab layers of the Bcase with two numerically improved building systems. In these two numerical scenarios, the roof slabs were modified to represent improvement strategies and to observe the thermal behaviour over the 21st century. The modifications in the proposed scenarios followed the NMX specifications. They correspond to Mexico's most used building systems (Table 3). The NMX specifies that the Bcase presents to thermal zone 3 and must comply with the thermal resistance designated for roof slabs. While the locations in thermal zone 4 must also comply with the specifications for the wall with the most sunlight.

Table

3

Thermal

properties of the building systems used in the numerical scenarios.

The joist and vault layer was analysed and divided into homogeneous and non-homogeneous sections to consider thermal bridges and heat transfer according to the NMX calculation.

Simulations

were made in EnergyPlus 9.5, and the model considers the presence of

a tenant who provided an activities profile. In this study, climate

data generated with Meteonorm software was used. Meteonorm integrates

sources such as the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP5)

(Taylor et al. 2012) and official IPCC projections (AR5) for future

scenarios, specifically through Representative Concentration Models

(RCPs). Meteonorm employs a climate anomaly-based approach, applying

projected differences between future and current climates (derived

from CMIP5 model outputs) to interpolated historical meteorological

data. This results in a synthetic climate series representative of

the future under a specific RCP, ensuring statistical and spatial

consistency for the study location. The result is a climate file in

EPW (EnergyPlus Weather) format, compatible with the energy

simulation tool used in this work.

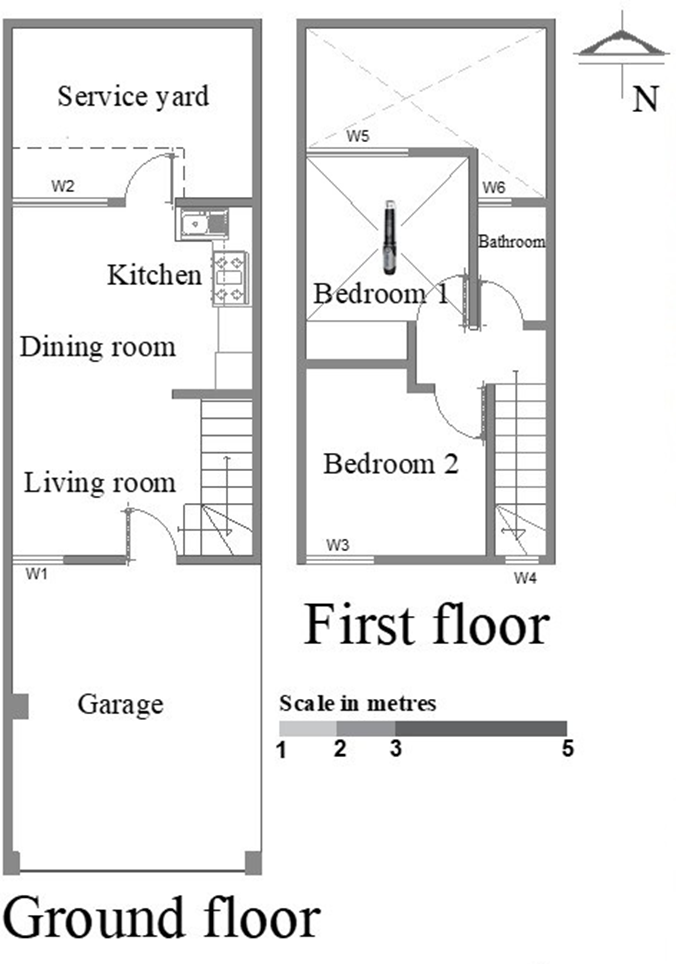

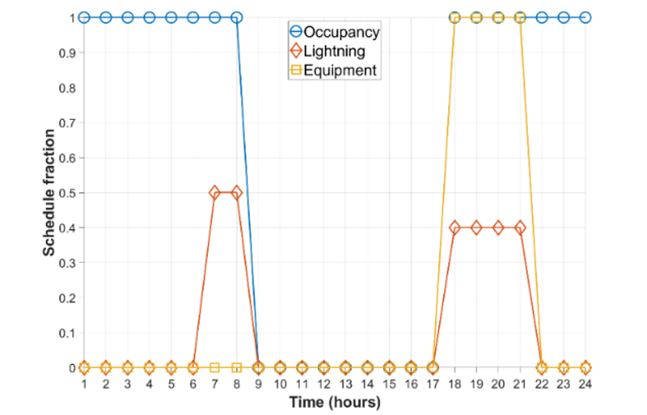

This profile reflects weekdays, weekends, and the level of clothing thermal insulation related to notable seasonal changes in the study region (summer and winter). Figure 4 shows the internal heat gain timetable on a typical working day for bedroom 1. Internal heat gains represent existing heat sources inside, such as electrical equipment and lighting, characterised by their design power level and the metabolic rate of people defined as a function of their level of physical activity. Other timetable items include natural ventilation, modelled using an Airflow Network (AFN), as the house has no HVAC system. The AFN model considers the airflow between zones due to infiltration and door and window openings with seasonal variations (such as fully closed doors and windows during winter).

The numerical analysis covers the current year's hourly baseline simulation and two future prospectives (2050 and 2100) that include the effects of climate change with Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) scenarios that consider radiative forcing, carbon cycling, gas loss in the tropics and absorption at different latitudes. The RCP models consider different global scenarios that focus on carbon increase with varying levels of impact. Three different RCPs were considered in the numerical simulation process. RCP 2.6, where variables such as CO2, temperature and radiative forcing are considered with a low impact and 1 °C to 1.5 °C temperature rise. RCP 4.5 was also considered, which is viewed as a scenario with an intermediate impact (1.5 °C to 2.4 °C temperature rise). Finally, RCP 8.5 was considered as a pessimistic scenario (3 °C to 4.8 °C temperature rise) (Hewitt et al., 2021)

Figure

4

The

internal heat gain timetable for Bedroom 1

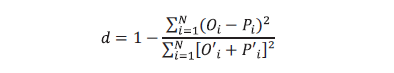

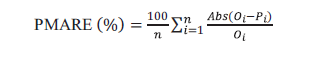

To analyse the observed (O) versus projected (P) data, it wasdetermined to use a pairwise review of two models, the one defined by Willmott (1982) and an index developed by M. H. Ali & Abustan (2014). The Willmott index standardises the degree of error to a range between 0 and 1 (Eq. 1). Where zero indicates a higher degree of error. Ali et al. evaluated the most used indices: Willmott, mean error (ME), root mean square error (RMSE), correlation coefficient (r) and relative error (RE), and developed a new evaluation model (PMARE) evaluated in percentage 0<PMARE<100 where 15% is considered an acceptable percentage (Eq. 2).

Where:

,

,

,

,

is the observed value,

is the observed value,

is the simulated value and

is the simulated value and

is the simulated mean.

is the simulated mean.

Where:

;

;

.

.

The validation process results, with 1668 data, were analysed, corresponding to the months of measurement from June to September 2022. Both the Willmott scale and the PMARE index show good results.

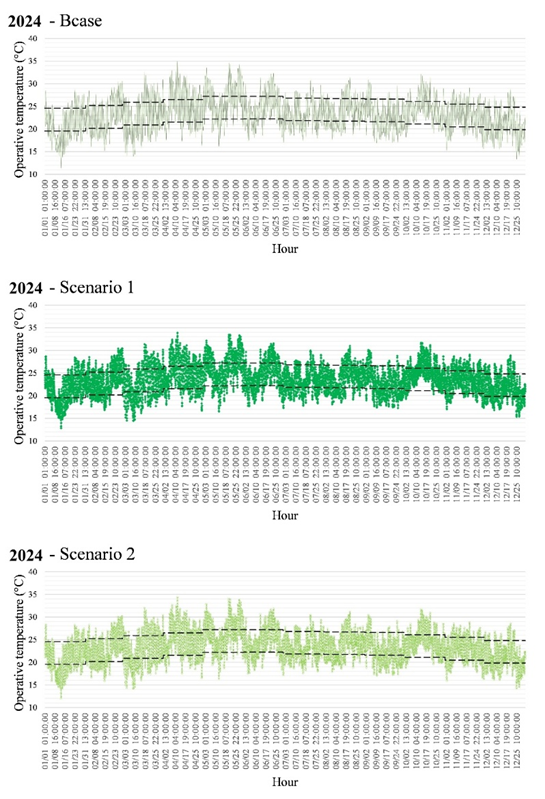

Due to the characteristics of the Bcase and air stratification, the highest temperatures throughout the year are concentrated on the first floor, where the bedrooms and bathroom are located., Therefore, the analysis of the thermal performance in Bedroom 1 was prioritised to observe the worst thermal scenario in all cases. Figure 5 shows the operative temperature behaviour 2024 in the Bcase and the two proposed numerical scenarios.

Figure

5

Operative

temperature behaviour in Bedroom 1 in 2024

The modification in roof slabs specified in the previous section was applied in both numerical scenarios. According to the ASHRAE 55 specifications, the comfort range for the warmest month is between 19.6 °C and 24.6 °C (80% of satisfied users). The data indicates higher space cooling and heating needs in the Bcase, which has a more significant temperature swing than the numerical scenarios. The numerical scenarios had a minor fluctuation and a difference in operative temperature between 0.5 °C and 1 °C. These results are essential if we consider that this difference occurs throughout the year and that the BSh climate of the Bcase belongs to the central zone of Mexico, where the greatest number of inhabitants is concentrated.

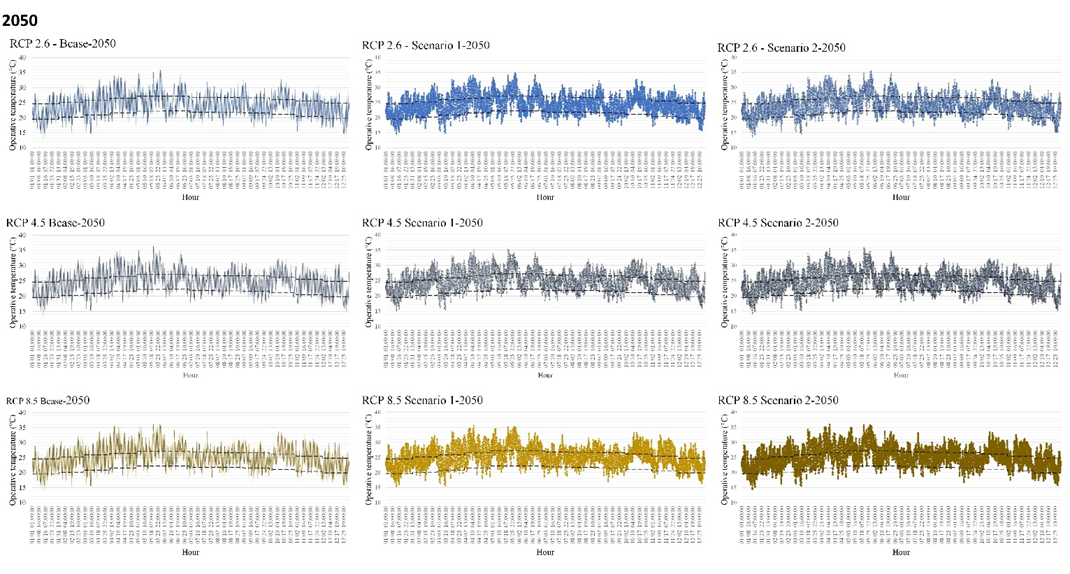

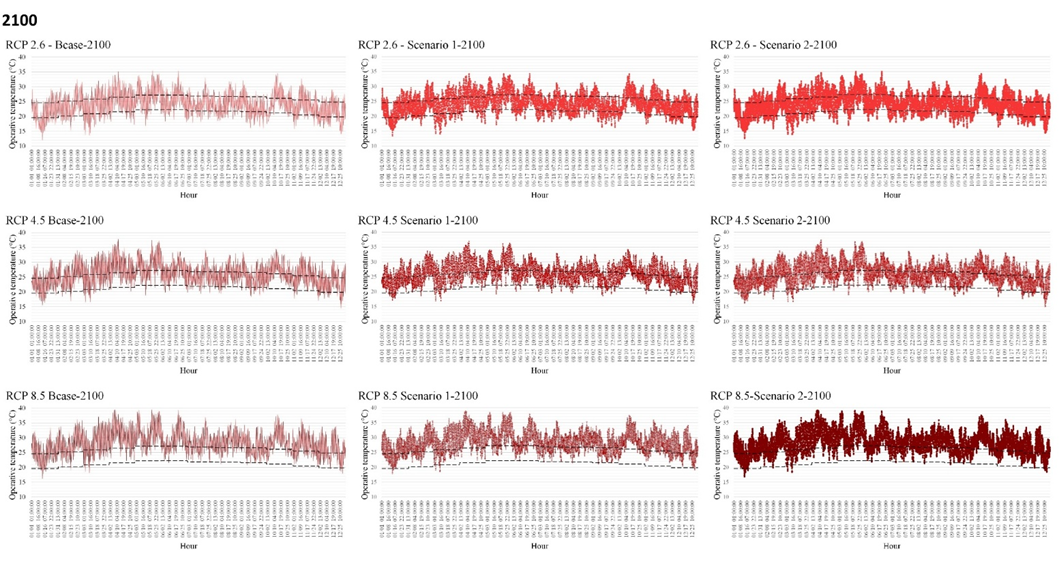

Figures 6 and 7 present the operative temperature in Bedroom 1, corresponding to 2050 and 2100, with RCPs 2.6, 4.5 and 8.5, respectively. In all cases, the Bcase presented a lower control of heat transfer indoors, with the highest temperature during the summer and the lowest during the winter. In the worst-case scenario (RCP 8.5), a temperature increase was observed in the Bcase ranging from 1.5 °C in the medium term (2050) to 4.5 °C in 2100. In the intermediate scenario (RCP 4.5), the maximum temperature reached 2.8 °C higher than the Bcase in 2024.

The operative temperature in 2050 remained unchanged with RCP 2.6 in Scenarios 1 and 2, where insulation and thermal improving layers were considered. In the worst case with RCP 8.5 showed an increase of 1 °C in Scenario 2 and 0.6 °C in Scenario 1. By 2100, RCP 4.5 showed a rise of 2 °C and 2.4 °C in Scenarios 1 and 2, respectively.

Finally, under the most pessimistic scenario (RCP 8.5) for 2100, a reduction of approximately 4 °C in operative temperature was observed in Scenarios 1 and 2 compared to the Bcase under the same conditions. All scenarios analysed showed that building systems with insulation and waterproofing layers (Scenarios 1 and 2) improve heat transfer inside buildings throughout the 21st century.

Figure

6

Operative

temperature over the 21st century in Bedroom 1 for 2050

Figure

7

Operative

temperature over the 21st century in Bedroom 1 for 2100

The building systems used in Scenarios 1 and 2 showed better indoor temperature control. The thermal properties of the concrete slab affected the total thermal resistance of Scenario 1, which, even with an air cavity, failed to outperform Scenario 2. As specified in NMX-C-460-ONNCCE-2009 (2009), the total R-value of the layers in the roof slab was obtained according to its homogeneous and non-homogeneous systems. For a non-homogenous building portion envelope, such as the prefabricated concrete joist and vault system used in Scenario 2, the partial thermal resistance RM comprises the homogenous thermal layers.

Discussion

Limited scientific progress highlights the need for improved energy policies, particularly in developing nations like Mexico. Rising global energy consumption sparks debate on equitable distribution and climate change mitigation, especially for vulnerable populations. Energy policies aim to reduce social inequality and lessen climate change impacts. This understanding frames the analysis of results, addressing the knowledge gap on the current and future effects of existing energy policies in developing countries.

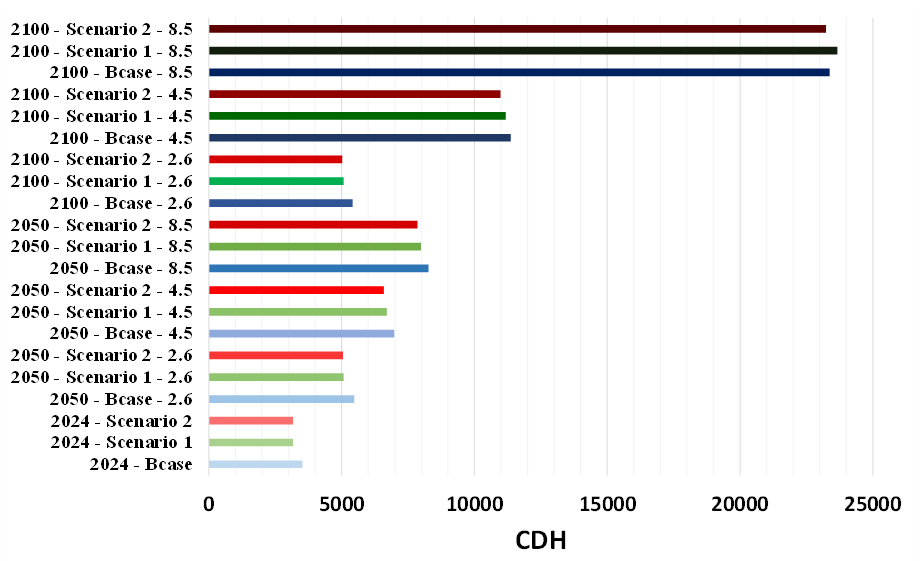

Figure

8

CDH

over the 21st century in Bedroom 1 for all scenarios

Figure 8 shows the results of this study, which indicate a decrease in cooling needs in Scenarios 1 and 2, where the roof slab construction system was improved (according to the layers shown in Table 3). The scenarios with efficient building systems project an 11% reduction in annual cooling energy demand from 2024 to 2100 in Mexico’s third most populous city with temperate climate. Furthermore, the reduction in cooling degree hours (CDH) observed in Scenario 2 and the improved overall thermal performance of Scenario 1, in line with NMX-C-460-ONNCCE-2009, demonstrate the effectiveness of these improvements in mitigating heat gains and optimising thermal comfort. This finding contributes to the effort to improve the quality of life of people with fewer resources by reducing the energy demand associated with space conditioning and advancing towards energy equity.

On the other hand, the results demonstrate that 30-year-old construction systems are obsolete and fail to meet current national standards. Researchers like Escandón et al. (2019) suggest that such energy and construction obsolescence fuels inequality, which could be lessened by employing passive systems and energy policies to minimize heat gains through the building envelope. Bodach et al. (2010) concur, noting these measures also benefit household economies in developing countries by lowering energy expenses.

Belaïd (2022) suggested including broader, localized social development actions is key for effective energy policies. Nationally, analyzing energy policies remains challenging. Researchers like Vázquez-Torres et al. (2022), Ruiz (2019), and Medrano-Gómez et al. (2017) have quantitatively verified the energy efficiency of Mexican public housing policies, recognizing the medium and long-term need for interdisciplinary, participatory methodologies to achieve greater impact. Consistent with previous findings, short-term results confirm that slab layer improvements in temperate climates effectively reduce indoor heat transfer and generate energy savings. However, future projections indicate that climate change effects create uncertainty about the scope of the analyzed NMX, necessitating its reformulation to ensure social equity.

Martín-Domínguez et al. (2017) proposed revising the NOM-020-ENER methodology due to calculation deficiencies, like omitting solar absorptivity. Periodic revision of energy policy methods is essential to adapt to evolving social, economic, and environmental conditions. This study highlights prioritizing analyses that include future climate change effects. Crucially, long-term scenarios predict the study locality's climate will shift from temperate to warm, with average temperatures risingfrom 22 ∘C to 28 ∘C under the worst-case scenario (RCP 8.5). This challenges current energy policies and their adaptation, risking energy poverty. Therefore, energy policies in developing countries require a large-scale design (Belaïd & Flambard, 2023) incorporating a macroeconomic view of energy consumption to tackle inequality. At the medium scale, policies should consider review and transition periods where researchers and stakeholders can resolve inaccuracies. Furthermore, at the household scale, users and technicians must have tools to apply regulations without technical or complicated processes. Considering economic, comfort, and environmental impacts at all scales is vital for increasing energy policy effectiveness.

Conclusions

This study examined the thermal performance of Mexico's most common social housing model, focusing on compliance with the mandatory NMX-C-460-ONNCCE-2009 standard for reducing heat gain. It also considered climate change impacts on dwellings throughout the 21st century, highlighting the need for developing countries to regularly update energy policies.

Key findings include a potential operative temperature reduction of over 4 C under the most pessimistic climate change scenario (RCP 8.5) compared to the base case (Bcase). This underscores the importance of design and construction choices in minimizing long-term energy consumption. Regional construction habits significantly affect indoor heat transfer, emphasizing the need for energy policies that integrate recommendations early in the design process.

Numerical scenarios projected an 11% reduction in annual cooling energy demand from 2024 to 2100 in Mexico's third most populous city, impacting over 2 million users. While Scenario 2 showed a reduction in CDH at the end of the century under RCP8.5 compared to the Bcase, Scenario 1 demonstrated the best overall thermal performance and was in line with the NMX-C-460-ONNCCE-2009 standard. These results call for a review of building envelope regulations focused on mitigating future climate variations.

This study concludes that developing countries must review energy policies to address changing dynamics affecting human and environmental health. Mexico's residential energy standards, including mandatory policies like NMX-C-460-ONNCCE-2009 aimed at reducing energy consumption, need to adapt to mitigate climate change effects. The projected increase in cooling needs in temperate climates presents a national challenge requiring timely mitigation strategies and adjustments to energy policies for user well-being. A methodological review of mandatory energy policy calculations and a national characterization of local building systems, focusing on envelope thermal performance, are recommended.

Acknowledgements

The first author gratefully acknowledges financial support from SECIHTI (CVU No. 181807) to pursue a postdoctoral fellowship. This activity was the result of collaboration with the international project: LINCGLOBAL MARS, on Mitigation, Adaptation and Resilience: towards a paradigm shift in domestic energy, with reference LINCG25032.

Final

Approval of the Article

MSc. Arch. Andrea Castro Marcucci, Editor-in-Chief.

Authorship

Contribution

Claudia Eréndira Vázquez Torres: The author contributed to Conceptualization, Project administration, Investigation, Methodology, Planning, Supervision, Writing – original draft, and Writing – review & editing. for creating concepts, planning, conducting research, and preparing manuscripts.

Gabriel Hernández Pérez: The author contributed to Conceptualization, Project administration, Investigation, Methodology, Planning, Supervision, Writing – original draft, and Writing – review & editing. for creating concepts, planning, conducting research, and preparing manuscripts.

Data

Availability

The data used in this research are not available in a public database. However, those interested in accessing the dataset may request it directly from the corresponding author: Claudia Eréndira Vázquez Torres.

References

Alford-Jones, K. (2022). How injustice can lead to energy policy failure: A case study from Guatemala. Energy Policy, 164(March), 112849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2022.112849

Alhazmi, M., Sailor, D. J., & Anand, J. (2022). A new perspective for understanding actual anthropogenic heat emissions from buildings. Energy and Buildings, 258, 111860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2022.111860

Ali, M. H., & Abustan, I. (2014). A new novel index for evaluating model performance. Journal of Natural Resources and Development, 2002, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.5027/jnrd.v4i0.01

Alpuche Cruz, M. G., & Duarte Aguílar, E. A. (2017). La NOM-020-ENER-2011 en viviendas económicas ubicadas en diferentes regiones climáticas de México. Vivienda y Comunidades Sustentables, 1(1), 75–90. https://doi.org/10.32870/rvcs.v0i1.6

American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, Inc. (2021). ASHRAE Standard 55-2020. In ASHRAE (Vol. 2, Issue 1). https://doi.org/10.1016/0140-7007(79)90114-2

Andrew, K., Majerbi, B., & Rhodes, E. (2022). Slouching or speeding toward net zero? Evidence from COVID-19 energy-related stimulus policies in the G20. Ecological Economics, 201(August), 107586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2022.107586

ASHRAE. (2018). ANSI/ ASHRAE/ IES Standard 100-2018: Energy Efficiency in Existing Buildings. 2018, 14.

Bai, H., Gao, W., Zhang, Y., & Wang, L. (2022). Assessment of health benefit of PM2.5 reduction during COVID-19 lockdown in China and separating contributions from anthropogenic emissions and meteorology. Journal of Environmental Sciences (China), 115, 422–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jes.2021.01.022

Belaïd, F. (2022). Implications of poorly designed climate policy on energy poverty: Global reflections on the current surge in energy prices. Energy Research and Social Science, 92(August), 102790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2022.102790

Belaïd, F., & Flambard, V. (2023). Impacts of income poverty and high housing costs on fuel poverty in Egypt: An empirical modeling approach. Energy Policy, 175(January). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2023.113450

Bodach, S., & Hamhaber, J. (2010). Energy efficiency in social housing: Opportunities and barriers from a case study in Brazil. Energy Policy, 38(12), 7898–7910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2010.09.009

Cadaval, M., Regueiro-Ferreira, R. M., & Calvo, S. (2022). The role of the public sector in the mitigation of fuel poverty in Spain (2008–2019): Modeling the contribution of the Bono Social de Electricidad. Energy, 258, 124717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2022.124717

Cengel, Y. A., & Ghajar, A. J. (2015). Heat and Mass Transfer. Fundamentals and applications (Mc Graw Hill Education, Ed.; Fifth Edit).

Chévez, P. J., Ruggeri, E., Martini, I., & Discoli, C. (2019). Factores Clave En La Implementación De Políticas Energéticas En Italia. Revista Produção e Desenvolvimento, 5, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.32358/rpd.2019.v5.384

Diario Oficial de la Federación. (2009). NMX-C-460-ONNCCE-2009 BUILDING INDUSTRY – INSULATION – “R” VALUE FOR THE HOUSING ENVELOPE BY THERMAL ZONE FOR MEXICAN REPUBLIC – SPECIFICATION AND VERIFICATION.

Diario Oficial de la Federación. (2011). Mexican Official Standard NOM-020-ENER-2011. http://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5203931&fecha=09/08/2011

Encuesta Nacional de Vivienda. (2021). Comunicado de Prensa. Encuesta Nacional de vivienda (ENVI), 2020 . Principales resultados. In Comunicado de Prensa 493/21 (Vol. 1).

Escandón, R., Suárez, R., & Sendra, J. J. (2019). Field assessment of thermal comfort conditions and energy performance of social housing : The case of hot summers in the Mediterranean climate. Energy Policy, 128(July 2018), 377–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2019.01.009

European Committee for Standardization. (2001). ISO 7726 Ergonomics of the thermal environment — Instruments for measuring physical quantities. In Iso 7726:2001 (Issue 1).

Fabbri, Kristian, Gaspari, J. (2021). Mapping the energy poverty: A case study based on the energy performance certificates in the city of Bologna. Energy and Buildings. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2021.110718

Gatto, A. (2022). The energy futures we want: A research and policy agenda for energy transitions. Energy Research and Social Science, 89(March), 102639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2022.102639

Griego, D., Krarti, M., & Hernández-Guerrero, A. (2012). Optimization of energy efficiency and thermal comfort measures for residential buildings in Salamanca, Mexico. Energy and Buildings, 54, 540–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2012.02.019

Hewitt, R. J., Cremades, R., Kovalevsky, D. V., & Hasselmann, K. (2021). Beyond shared socioeconomic pathways (SSPs) and representative concentration pathways (RCPs): climate policy implementation scenarios for Europe, the US and China. Climate Policy, 21(4), 434–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2020.1852068

INEGI. (2020). Marco Geoestadístico Municipal. Sistema de Clasificación Climática de Köppen (1936) Modificado Por Enriqueta García (1973) e INEGI (1976). http://cuentame.inegi.org.mx/mapas/pdf/nacional/tematicos/climas.pdf

INEGI; Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. (2022). Inventario Nacional de Vivienda. https://www.inegi.org.mx/temas/vivienda/

INEGI, Instituto Nacional de Geografía, E. e I. (2023). Population. Population. https://cuentame.inegi.org.mx/poblacion/habitantes.aspx?tema=P

Jiglau, G., Bouzarovski, S., Dubois, U., Feenstra, M., Gouveia, J. P., Grossmann, K., Guyet, R., Herrero, S. T., Hesselman, M., Robic, S., Sareen, S., Sinea, A., & Thomson, H. (2023). Looking back to look forward: Reflections from networked research on energy poverty. IScience, 26(3), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2023.106083

Jonek-Kowalska, I. (2022). Multi-criteria evaluation of the effectiveness of energy policy in Central and Eastern European countries in a long-term perspective. Energy Strategy Reviews, 44(May), 100973. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esr.2022.100973

Littlewood, J. R., Karani, G., Atkinson, J., Bolton, D., Geens, A. J., & Jahic, D. (2017). Introduction to a Wales project for evaluating residential retrofit measures and impacts on energy performance, occupant fuel poverty, health and thermal comfort. Energy Procedia, 134, 835–844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2017.09.538

Liu, Y., Luo, Z., & Grimmond, S. (2023). Impact of building envelope design parameters on diurnal building anthropogenic heat emission. Building and Environment, 234(February), 110134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2023.110134

Martín-Domínguez, I. R., Romero-Pérez, C. K., Nájera-Trejo, M., & Rodríguez-Muñoz, N. A. (2017). Implicaciones en las consideraciones metodológicas de la NOM-020-ENER. Semana Nacional de Energía Solar, 52(614).

Medrano-Gómez, L. E., & Izquierdo, A. E. (2017). Social housing retrofit: Improving energy efficiency and thermal comfort for the housing stock recovery in Mexico. Energy Procedia, 121, 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2017.08.006

Ruiz Torres, R. P. (2019). Evaluación Del Sistema Termolosa Entre La Medición Experimental Y El Calculado Con La Nmx-C-460-Onncce-2009. Vivienda y Comunidades Sustentables, 2019(6), 119–136. https://doi.org/10.32870/rvcs.v0i6.126

Taylor, K. E., Stouffer, R. J., & Meehl, G. A. (2012). An overview of CMIP5 and the experiment design. Bulletin of the American meteorological Society, 93(4), 485-498. https://journals.ametsoc.org/view/journals/bams/93/4/bams-d-11-00094.1.xml

Secretaría de Energía. (2013). Prospectiva del Sector Eléctrico 2013-2027.

Sistema Meteorológico Nacional. (2020). Climatic conditions. https://smn.conagua.gob.mx/es/climatologia/informacion-climatologica/normales-climatologicas-por-estado

Vázquez-Torres, C. E., Sotelo-Salas, C., & Grajeda-Rosado, R. M. (2022). Efecto de la NMX-C-460-ONNCCE-2009 sobre el Comportamiento Térmico en Viviendas de Interés Social en Clima Templado Sub-Húmedo. In Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana (Ed.), Estudios de Arquitectura Bioclimática (pp. 109–124).

Willmott, C. J. (1982). Some comments on the evaluation of model performance. Bulletin - American Meteorological Society, 63(11), 1309–1313. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0477(1982)063<1309:SCOTEO>2.0.CO;2