Conceptual Metaphors: an Insight into Teachers’ and Students’ EFL Learning Beliefs

Metáforas conceptuales: una visión de las creencias de los profesores y estudiantes sobre el aprendizaje del inglés como lengua extranjera

Metáforas conceituais: uma visão das crenças de professores e estudantes sobre a aprendizagem do inglês como língua estrangeira

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18861/cied.2022.13.2.3176

Natalia

Zambon Ferronato

Universidad

ORT Uruguay

Uruguay

nataliazf@yahoo.com

ORCID:

0000-0001-7877-985X

Recibido:

26/08/21

Aprobado:

15/11/21

Cómo

citar:

Zambon

Ferronato, N. (2022). Conceptual metaphors: an insight into teachers’

and students’ EFL learning beliefs. Cuadernos

de Investigación Educativa,

13(2).

https://doi.org/10.18861/cied.2022.13.2.3176

Abstract

Teachers and students hold their own language learning beliefs about English as a Foreign Language (EFL). In the classroom, students’ and teachers’ beliefs interact, which might result in either tension or opportunities for change. Considering that it might be difficult to evoke some of the participants’ beliefs, this study opted to analyze conceptual metaphors as an indirect way to elicit them. Metaphors are part of our thoughts and actions and, sometimes, they are the only way of organizing and expressing our experiences coherently (Lakoff & Johnson, 2003). This study analyzed, through metaphor analysis, how students’ beliefs about learning EFL relate to the teacher’s selection and use of language learning strategies (LLS) in the classroom. The study occurred at an English Institute in Montevideo, Uruguay, between October and November 2018. The methodology of this multiple case study was qualitative. The participants were three EFL teachers and four groups of students ranging from basic to advanced level. Students were asked to respond to the following prompt with a metaphor: “For me, learning English as a foreign language is (like)… because…”. Then they wrote a letter advising a future EFL student. Teachers answered a structured interview in which they provided a metaphor describing the work with their groups. The most heterogeneous group in terms of age was selected for a follow-up structured interview. Results indicate that metaphors not only shed light upon how students perceive their learning process, but also encourage reflection. The study also found that several factors influence teachers’ selection of language learning strategies, including the role of international exams. We can conclude that visible interactions that happen in class are like the tip of an iceberg - beliefs lie hidden from view.

Keywords: conceptual metaphor, language learning beliefs, language learning strategies, EFL, teacher cognition.

Resumen

Docentes y estudiantes presentan creencias sobre el aprendizaje de inglés como lengua extranjera. Es en el aula donde esas creencias se encuentran, pudiendo generar puntos de tensiones o habilitaciones de cambio. Debido a la dificultad para tener acceso a las creencias, se optó por investigarlas de una manera indirecta, a través de la metáfora conceptual. La metáfora está presente en nuestros pensamientos y acciones y, en muchos casos, pueden ser la única manera de organizar y expresar nuestras experiencias de forma coherente (Lakoff & Johnson, 2003). Esta investigación analizó, a partir de metáforas conceptuales, la relación entre las creencias de estudiantes sobre el aprendizaje de inglés como lengua extranjera y la posible influencia en la selección de las estrategias para el aprendizaje de lenguas por el docente. El estudio se realizó en un instituto de Montevideo, Uruguay, entre octubre y noviembre de 2018. La metodología de este estudio de casos fue cualitativa. Los participantes fueron tres docentes y cuatro grupos de estudiantes de nivel básico al avanzado. Las metáforas fueron recolectadas a través de la oración: “Según su opinión, aprender inglés como lengua extranjera es (como)… porque…”. Los estudiantes también escribieron una carta a un futuro estudiante. Los docentes tuvieron una entrevista estructurada donde crearon una metáfora sobre sus grupos. Se seleccionó el grupo más heterogéneo en cuanto a edad para entrevistar. Los resultados indican que las metáforas no sólo arrojan luz sobre cómo estudiantes perciben su proceso de aprendizaje, sino que también fomentan la reflexión. Se observó que existen diversos factores que influyen en la selección de las estrategias para el aprendizaje de lenguas, como el rol que implican los exámenes internacionales. Concluimos que las interacciones visibles que ocurren en clase son como la punta de un iceberg: las creencias están ocultas de la vista.

Palabras claves: metáfora conceptual, creencias de aprendizaje de lenguas, estrategias para el aprendizaje de lenguas, inglés como lengua extranjera, cognición docente.

Resumo

Professores e alunos apresentam crenças sobre o aprendizado do inglês como língua estrangeira. Na sala de aula, as crenças dos alunos e professores interagem, o que pode resultar em tensão ou oportunidades de mudança. Considerando a dificuldade de ter acesso às crenças dos participantes, optou-se por evocá-las de uma maneira indireta, usando metáforas conceituais. As metáforas fazem parte de nossos pensamentos e ações e, às vezes, são a única forma de organizar e expressar nossas experiências de forma coerente (Lakoff & Johnson, 2003). Este estudo analisou, por meio de metáforas, a relação entre as crenças dos alunos sobre a aprendizagem de inglês como língua estrangeira e a possível influência na seleção de estratégias de aprendizagem de línguas pelo professor. O estudo ocorreu em um Instituto de Inglês em Montevidéu, Uruguai, entre outubro e novembro de 2018. A metodologia deste estudo de caso foi qualitativa. Os participantes foram três professores de EFL e quatro grupos de alunos do nível básico ao avançado. As metáforas foram coletadas por meio da frase: “Na sua opinião, aprender inglês como língua estrangeira é (como)… porque...”. Os alunos também escreveram uma carta para um futuro aluno. Os professores responderam a uma entrevista estruturada na qual forneceram uma metáfora descrevendo o trabalho com seus grupos. O grupo mais heterogêneo em termos de idade foi selecionado para uma entrevista estruturada. Os resultados indicam que as metáforas não apenas iluminam como os alunos percebem seu processo de aprendizagem, mas também estimulam a reflexão. O estudo também descobriu que vários fatores influenciam a seleção dos professores de estratégias de aprendizagem de línguas, incluindo o papel dos exames internacionais. Concluímos que as interações visíveis que acontecem em sala de aula são como a ponta de um iceberg - as crenças permanecem ocultas.

Palavras-chave: metáfora conceitual, crenças de aprendizagem de línguas, estratégias de aprendizagem de línguas, inglês como língua estrangeira, cognição docente.

Introduction

This article is based on the thesis presented to obtain a Master's in Education from Universidad ORT Uruguay in 2019. The thesis - ¿Qué piensan los docentes y los estudiantes del aprendizaje del inglés como lengua extranjera?: un estudio sobre creencias a partir de la metáfora conceptual– is about students’ language learning beliefs regarding English as a Foreign Language (EFL), analyzed through conceptual metaphors (Zambon, 2019).

Understanding teachers' and students' beliefs contributes to improving teaching and learning; it even encourages reflection and opens the opportunity for dialogue on this key issue. In the classroom, teachers’ and students’ beliefs interact, which might generate tension when they mismatch or enable changes. In addition, students' beliefs may influence teachers' approach in class, mainly in the selection and use of language learning strategies (LLS).

Importance of the study

The idea for this research came from the study of Barcelos (2003b), in which the author emphasizes the fact that the interconnection between teachers’ and students’ beliefs is still unexplored. According to Barcelos, the few studies that explore this fail in two aspects: first, most use questionnaires or inventories that make it difficult to understand this relationship from an internal perspective, reinforcing an abstract vision of teachers’ and students’ beliefs since they are studied in a way disconnected from the classroom. Second, they look only at how teachers’ beliefs influence the formation of students' belief systems, and almost never the other way round.

How do we define belief? For the purpose of this article, beliefs are understood as:

a form of thought, constructions of reality, ways of seeing and perceiving the world and its phenomena which are co-constructed within our experiences and which result from an interactive process of interpretation and (re)signifying, and of being in the world and doing things with others. (Barcelos, 2014 as cited in Kalaja et al., 2015, p. 8)

Therefore, how do beliefs influence the way teachers teach? People, in general, are guided by an implicit theory, using their conceptions about the world to make decisions and interpret reality in their own way (Marrero et al., 1993). According to the authors, "implicit theories are individual representations based on the accumulation of personal experiences" (p. 14). Teachers learn from these professional experiences acquired over the years through interactions with students and other teachers, training courses, readings, and participation in seminars, in which each contributes to the formation of their belief systems (Barnard & Burns, 2012).

Borg (2003) emphasizes that “teachers are active, thinking decision-makers who make instructional choices by drawing on a complex, practically-oriented, personalized and context-sensitive networks of knowledge, thoughts and beliefs” (p. 81). However, even if teachers have deeply ingrained beliefs, they do not put all of them into practice, and the reasons are still unexplored (Barnard & Burns, 2012). According to Freeman (2002), reflecting on our beliefs has a great many advantages, such as seeing the thinking process behind teachers’ actions (which might contradict how they had learned to teach), expanding their pedagogical techniques, and revisiting their practice leaving room for improvement.

Theoretical framework

Research on language learning beliefs, especially in applied linguistics, is relatively new, gaining academic attention in the mid-1980s (Barcelos, 2003a). The early studies carried out on the topic are classified by Barcelos (2003a) into three approaches: normative, metacognitive, and contextual. Each approach presents a specific belief, conception and methodology of its own. In a subsequent publication, Beliefs, Agency and Identity in Foreign Language Learning and Teaching (2015), in which Barcelos is a co-author - research on language learning beliefs is classified into two essential approaches, traditional and contextual; the studies carried out in recent years follow these two approaches.

The traditional approach

Research that follows the traditional approach is based on the Beliefs About Language Learning Inventory (BALLI) created by Horwitz and published in 1985. BALLI is an inventory that consists of 27 statements presented on the Likert Scale, whose responses vary from 5 (I totally agree) to 1 (I totally disagree). The instrument was created to 1) try to better understand why teachers choose certain teaching practices and 2) determine where there may be conflicts between beliefs held by language teachers and their students. The author mentions that the instrument has served as a “useful discussion tool in inservice workshops and in methods classes” (Horwitz, 1985, p. 334). The 27 statements are divided into four main areas of foreign language learning: 1) the ability to learn foreign languages, 2) difficulty in learning languages, 3) the nature of language learning, and 4) strategies for learning languages.

BALLI is classified by Kalaja et al. (2015) as a classic among studies on beliefs about EFL learning. However, in this traditional approach, student beliefs are seen as preconceived notions, myths, or misconceptions (Horwitz, 1985, 1988). According to Hosenfeld (2003), student beliefs in the light of the traditional approach are generally seen as stable and are presented in the inventory as static notions. Even though Horwitz (1988) observes that there is a need to study whether beliefs change over time, the author acknowledges that BALLI does not offer this possibility since the items listed refer to static beliefs.

For Horwitz (1988), some beliefs can be an obstacle for students to learn a foreign language successfully; in such cases, teachers need to find the best way to challenge such beliefs. The ideas defended by the author allow us to conclude that teacher beliefs are, in a way, superior to student beliefs. The author also suggests that some student beliefs may be based on lack of experience or limited knowledge, which makes it the teacher's job to confront the beliefs considered erroneous.

The traditional approach presents some problems in investigating teacher and student beliefs. Ellis (2008) observes two specific problems. The first is related to the fact that students do not always voice their beliefs accurately. According to the author, one reason is that they reveal beliefs that they assume the researcher would like to hear. The second is that this type of instrument (closed-response questionnaires) assumes that students are aware of their beliefs and can verbalize them. For Ellis, although many students are aware of some of their beliefs and can convey them, it is possible that some are "below the threshold of consciousness or cannot be easily and directly expressed" (2008, p. 13). Barcelos (2003a) points out that this approach analyzes the responses to the questionnaires in a quantitative way using descriptive statistics and, therefore, beliefs are analyzed out of context, not allowing teachers and students to use their own words to indicate what they think.

The contextual approach

In recent years, researchers have used various theoretical frameworks, different ways of collecting data, and have analyzed beliefs under different methodologies, all of which, according to Barcelos (2003a), share some common assumptions about beliefs. Researchers using the contextual approach do not try to generalize but rather try to seek deep understanding in specific contexts; this way, beliefs are embedded in the context. This approach perceives beliefs as contextual, dynamic and socially constructed and, therefore, seeks to understand them where they occur (Hosenfeld, 2003; Kalaja et al.,2015).

The contextual approach, according to Barcelos, has a more positive view of the student than the traditional approach because it takes “students’ own perspective and context into account” (2000, p. 64). Furthermore, this approach sees students as social beings that interact in their environment, and therefore, experiences and context are relevant to this type of study (Barcelos, 2003a).

The metaphor as an instrument to analyze language learning beliefs

Metaphors are present in our daily life. They are the main mechanism through which not only do we understand abstract concepts but also reasoning (Lakoff, 1993). Lakoff and Johnson (2003) indicate that, in addition to metaphors being present in the language we use, they are part of our thoughts and actions, which results in our conceptual system being metaphorical in nature. However, Lakoff (1993) argues that in classical theories of language, metaphors were simply seen as language, but not as thought, as their nature is fundamentally conceptual and not linguistic. Metaphor, therefore, is used as a resource to understand how we think and act, other than being a poetic process (Lakoff & Johnson, 2003).

Conceptual metaphor is understood as:

A phenomenon of cognition in which one semantic area or domain is conceptually represented in terms of another. This means that we use our knowledge of a conceptual field, usually concrete or close to physical experience, to structure another field that is usually more abstract. (Soriano, 2012, p. 87)

Cameron and Low (1999) present an example: IDEAS ARE MONEY, in which A is B; they explain that: “a conceptual metaphor is hence a unidirectional linking of two different concepts, such that some of the attributes of one (MONEY) are transferred to the other (IDEAS)” (p. 78). Conceptual metaphors help us understand ideas when we transfer a more familiar concept to understand something that may be more difficult or abstract. Soriano (2012) continues to explain that:

We use our knowledge of a conceptual field, usually concrete or close to physical experience, to structure another field that is usually more abstract. The first is called strong domain, since it is the origin of the conceptual structure that we import. The second is called the target or destination domain. (p. 87)

Metaphorical mappings tend to vary in their universality; however, some tend to have universal characteristics, and others only seem to make sense within the culture in which they are embedded (Lakoff, 1993). The author also specifies that these mappings are not arbitrary but are rooted in everyday experiences and physical sensations. That is, people use metaphors in their daily lives, and their meaning can be understood by people from different cultural environments unless it is very specific to a certain culture or even micro-culture.

Lakoff and Johnson (2003) highlight that the use of metaphors can have impact on the way we think and act through the creation of realities, especially social realities. For the authors, we make use of metaphors to organize and express some aspect of our experience in a coherent way; sometimes using metaphors is the only possible way through which we can verbalize our thoughts and feelings. In recent decades, a significant number of investigations have been carried out using metaphors due to the fact that identification and discussion of metaphors can clarify implicit assumptions, as well as encourage personal reflection, resulting in an attempt to understand the perspectives of individual students and teachers on different topics (Cameron & Low, 1999). Several studies, including that of Fang (2015), who investigated 120 in-training EFL teachers in China, suggest that metaphors reveal key information concerning students’ ideas about their learning process. In that study, participants expressed that learning English is not easy, and that successful learning implies hard work, having confidence, a solid foundation, patience, and perseverance. This information is useful for teachers to help their students to develop their language learning abilities and be more confident.

Context of the study

Purpose of the study and research objectives

Teachers’ and students’ beliefs will interact in the classroom, which might lead to conflict when they mismatch. The reason for the conflict may be that students do not fully understand their teachers’ expectations, as well as their intentions and objectives. According to Weinstein (1983), cited by Johnson (1995), “student learning is enhanced when students accurately perceive teachers’ expectations and intentions” (p. 40). Barcelos (2000) adds that it is equally important for the process that teachers perceive the expectations and intentions of their students; even in cases where the differences are very marked, a situation can be triggered in which students are passive or resistant to learning.

For this study, it seems appropriate to use metaphors to research language learning beliefs. Ellis (2008) contemplates their use as an alternative approach to explore the way in which students talk about their learning experiences, considering that metaphors are an indirect way to access their beliefs. Therefore, participants can express concepts that could be difficult or even impossible without the use of metaphorical language. Metaphors allow the researcher to access beliefs that may be explicit or even implicit and that, in many cases, will not be evident in an interview or in a BALLI-type questionnaire. Additionally, participants express their thoughts without saying what they think the interviewer would like to hear.

Therefore, the goal of this study was to use conceptual metaphors to analyze the interconnection between students' beliefs about learning EFL in the classroom and the influence they might have on the selection of LLS by the teacher.

The objectives were to:

- Identify and map out students' language learning beliefs about learning EFL in the classroom through conceptual metaphors and the LLS they use.

- Analyze which aspects teachers’ and students’ beliefs about learning EFL in the classroom match and mismatch.

- Describe and interpret the possible influence of student beliefs on teacher selection of LLS to be used in the EFL classroom.

This research is a qualitative, multiple case study fully exploring the the participants' responses , taking into consideration the context - the classroom - in which they are inserted. According to Hernández Sampieri (2014), “qualitative research focuses on understanding phenomena, exploring it from the participants' perspective in a natural environment and in relation to their context” (p. 358). According to Flick (2015), the quality of qualitative work lies in the balance between the observation of methodological rigor and creativity (be it theoretical, conceptual, or practical) to study what is proposed.

The idea behind qualitative research is not to generalize the results obtained to the wider educational community, but rather to analyze the phenomenon in depth (Hernández Sampieri, 2014). In addition, the purpose of a case study is its particularity, aiming to fully understand it, without comparing it to other cases. Not everything constitutes a case study - it is necessary to present something specific; however, each classroom with its participants becomes unique and relevant (Stake, 1999).

In light of what has been explained in the previous section, the contextual approach has been chosen because it allows teachers and students to express their own beliefs freely, rather than reacting to already formulated statements. For Dufva (2003), the role of the researcher is to evoke beliefs, but always keep in mind that thoughts, and therefore beliefs, are something private to the participants, and not everyone may be prepared to discuss them.

Setting

The study was carried out at a language institute in Montevideo, Uruguay, between October and November 2018. The institute offers English courses for students of all ages. The language courses are conducted in person, once or twice a week. The institute also prepares students for international English exams, offers EFL teaching training courses, and provides academic support for teachers and schools from all over the country.

Participants

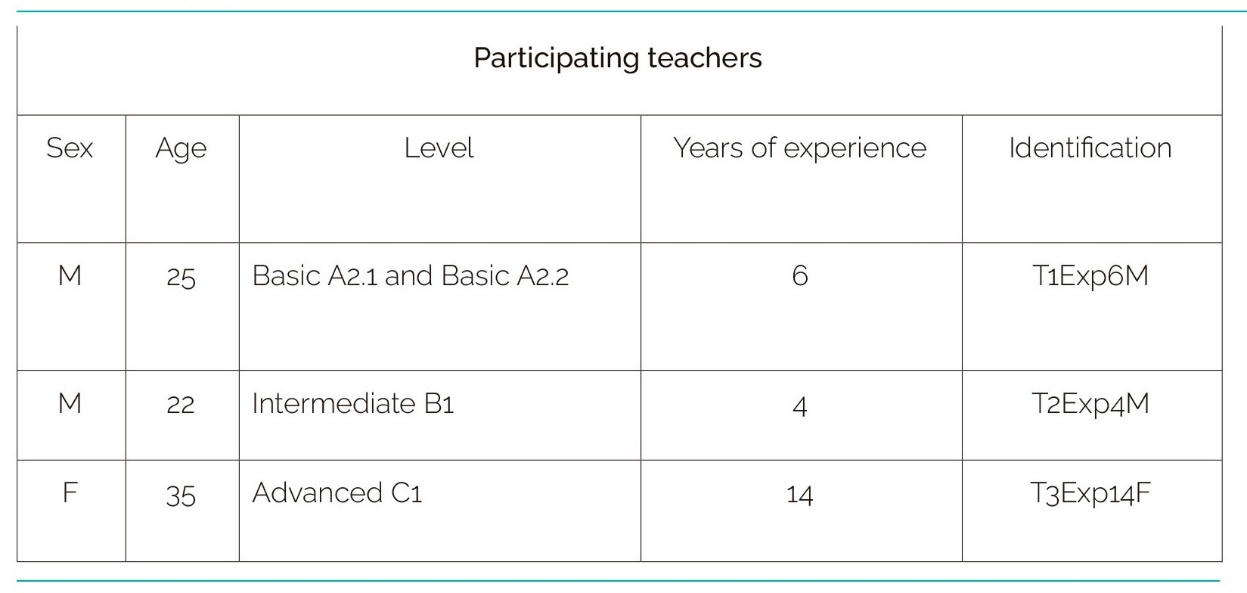

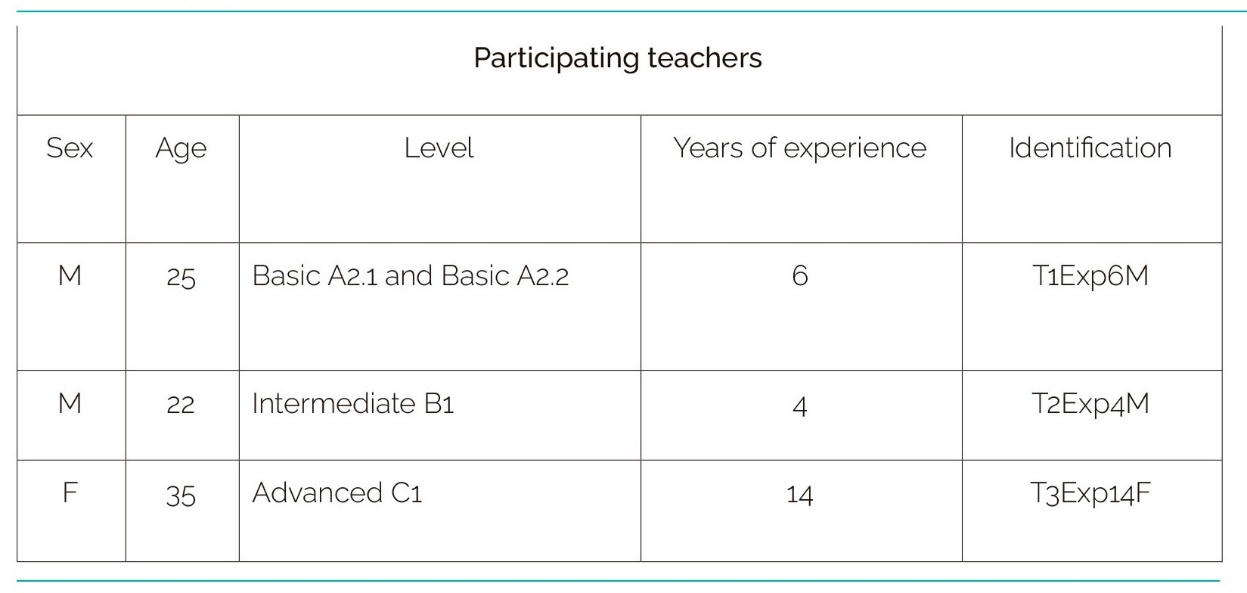

For the study, three EFL teachers and four groups of students were selected. The students chosen for the research were those who were in class on the day the researcher visited the groups to explain the study. The researcher visited five groups in total, but one of the basic level groups did not submit their metaphor and letter activities and, therefore, it was understood that they did not want to participate and was removed from the sample. The data is summarized in Table 1 and Table 2:

Table 1: Participating teachers

Note. Information organized by the author, based on the information provided by the participants

Table 2: Participating students

Note. Organized by the autor

The participating students are identified by a letter of the alphabet (A - O) with their age and sex in parenthesis. For example, student “A (19, F)” means that student A is a nineteen-year-old female.

Sample selection criteria

The groups were chosen by the institute, consisting of an intentional sample, not a random one. In addition, the institute avoided choosing groups that were already assigned for observation by teachers in training; the reason was to prevent those groups from having yet another interference. The institute was asked to select groups that were taught by the same teacher; for example, a teacher could have a basic and an intermediate group. It was intended to investigate a minimum of four teachers and their groups. From the selected groups, the one that was presented as the most heterogeneous (in terms of students’ age) was chosen for a semi-structured interview.

Phases of the study

The study was done in two phases: the first one was a visit to the groups when metaphor awareness was undertaken, and the students were asked to write a letter to a friend; the second consisted of conducting interviews with the participants.

Phase one:

1. Raising students’ awareness of the concept of metaphor and its importance for the study.

2. Metaphor sentence completion exercise: “For me, learning English as a foreign language is (like)… because…”.

3. Letter writing activity for a future EFL student.

4. Partial analysis of the data obtained.

Phase two:

1. Structured interview with the teachers whose groups participated in the study.

2. Semi-structured interview with students from one of the groups.

3. Final analysis of the data obtained.

Data-gathering instruments

Metaphor sentence

An investigation using metaphors does not mean that it will be easy to conduct or free from implementation problems. Wan and Low (2015) highlight that several studies using conceptual metaphors give the false idea that they are easy to carry out, mainly because most researchers do not report problems they have faced in provoking or collecting metaphors.

One of the potential problems is that the participants do not know or do not understand how to complete the metaphor sentence. Low (2015) points out that in a study involving few participants, it is crucial that everyone has the necessary conditions to be able to complete what is asked, especially when the idea is to deepen the answers obtained; however, in studies involving large numbers of participants and whose purpose is to determine a general trend, if some participants fail to produce a metaphor, this will not negatively impact the results.

Wan (2015) conducted a study involving Chinese Master’s degree students from an English university on their perception of the act of writing. She concluded that the reasons why the participants did not know how to complete the assigned metaphorical sentences were not due to personal characteristics, but to a lack of knowledge of metaphor and understanding why they had to produce them.

The decision to include the word 'like' in the metaphor sentence is to facilitate students’ understanding of what they are expected to write and avoid constructions such as Learning English is difficult - which does not qualify as a metaphor. The inclusion of the word 'like' transforms the sentence into a simile, which is also a literary device. It is not the purpose of this paper to discuss the difference between metaphor and simile.

In addition, participants were asked to write a brief explanation of their idea behind their metaphor by including the word 'because'. This is vital to include, as several researchers reported the need to obtain more data to interpret the metaphors and to determine if the answers are indeed metaphorical construction (Low, 2015; Armstrong, 2015). According to Low (2015), a potential problem is that the word 'because' seems ambiguous or repetitive; one of the solutions is for the participants to add an explanation even if it seems obvious.

The letter

Studies involving metaphors require supplemental data sources to prevent the researcher’s subjectivity from influencing the metaphor analysis and thus compromising the study’s validity (Seung et al., 2015).

The possibility of conducting focus groups was considered at first; the idea of asking students to keep journals about their learning experience was also entertained. Due to time constraints and, mainly, access to the groups, it was decided to ask the participants to write a letter for a future EFL student, offering them some useful LLS.

Limitations of the study

Class observation was not included, considering the time allotted to carry out the study. Through class observations, it would have been possible to perceive the relationship between the participating students among themselves and with their teacher. Also, it might have been interesting to witness some of the participants’ actions, which would justify their EFL beliefs described in their metaphors, letters, and interviews. The data would have served as a form of data triangulation.

Results and Discussion

Given the space constraints, this section will not offer a detailed analysis of each metaphor submitted by the participants but rather a group analysis based on the results drawn from the data collected, contrasted with the corresponding teachers’ metaphors.

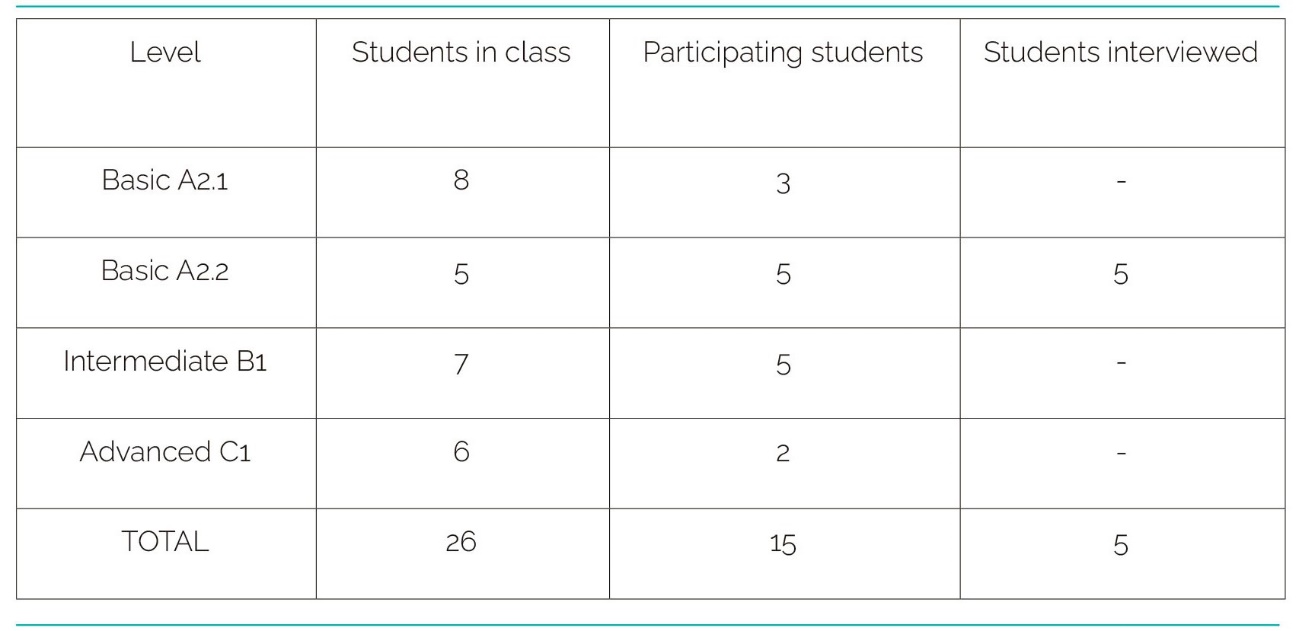

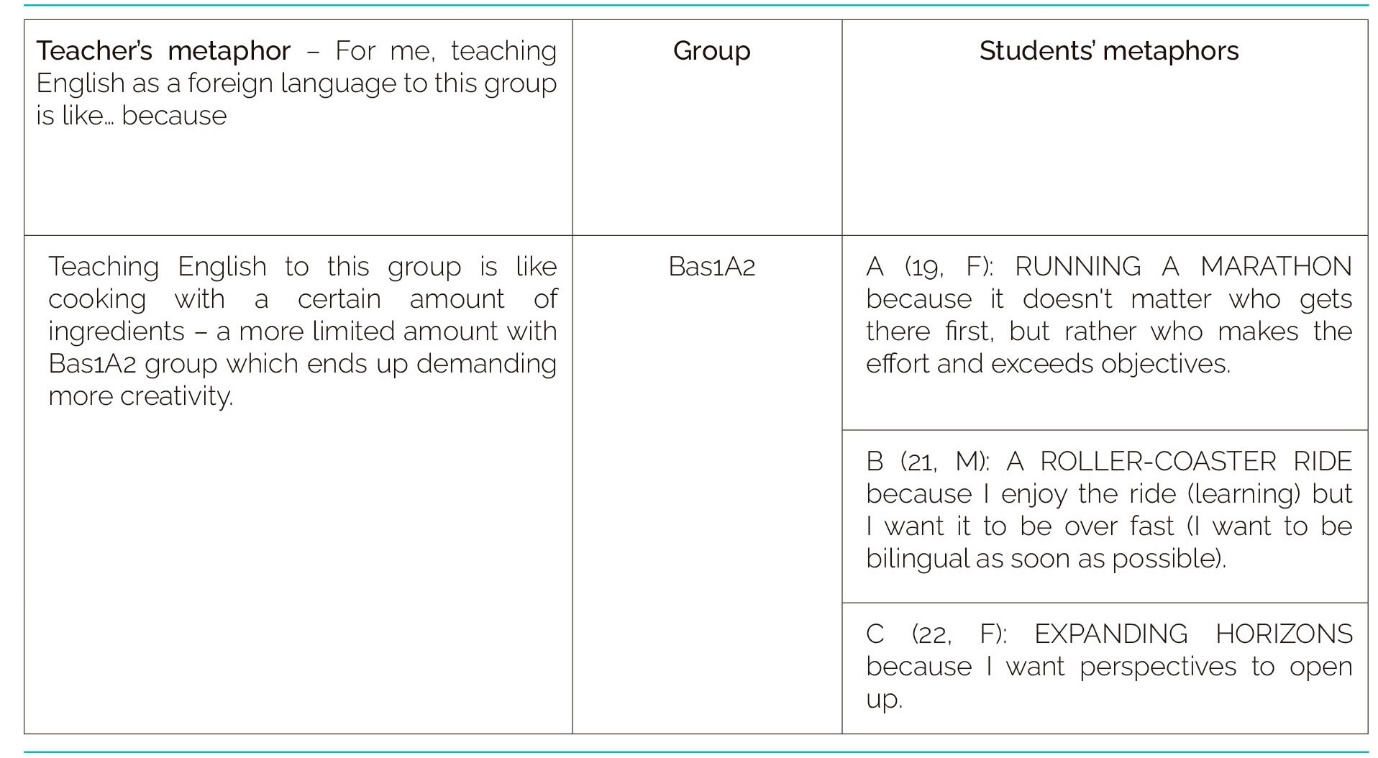

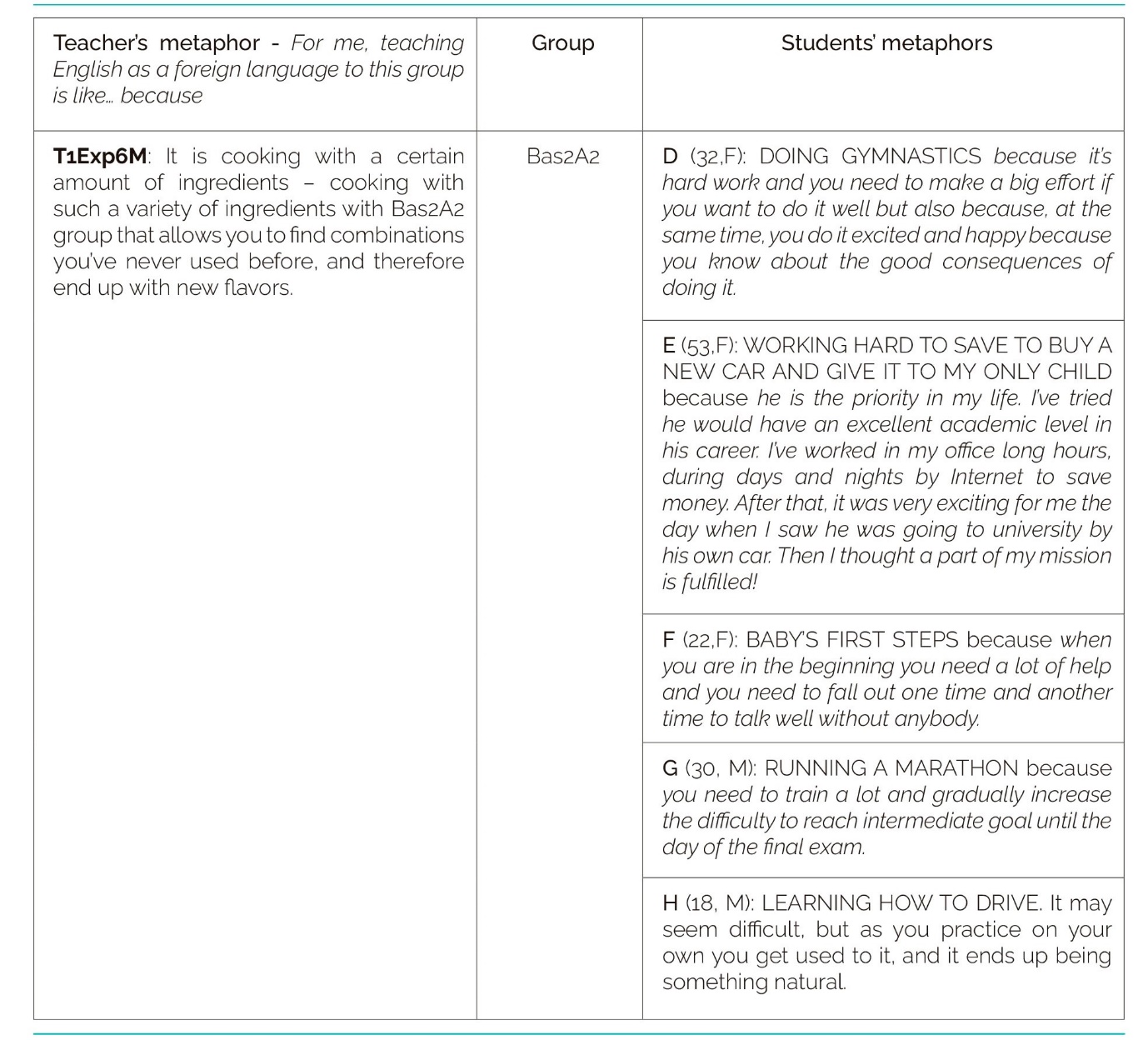

Case 1 – Teacher T1Exp6M, groups Bas1A2 and Bas2A2

Table 3: Teacher’s and students’ metaphors – A2.1 group

Note. Metaphors and explanation sentences have been translated by the author.

Cooking is an act of love, nurturing and caring for others, which requires effort. Cooking with a limited amount of ingredients makes the experience more challenging for the cook, demanding more creativity and extra effort to care for others.

By analyzing students’ metaphors and letters, it is possible to conclude that: student A’s metaphor - running a marathon – involves a great deal of work to learn a language; it may also refer to an activity shared by a group whose participants encourage one another, or to an exercise to be enjoyed alone. Student B comes to class looking for fun and adrenaline; he wants to have a quick and intense experience learning English, which translates into the fact that he desires to become fluent fast, but only “working” when in the classroom. As student C suggests, expanding horizons means looking for something new and fresh challenges; several of these involve being in contact with other people and understanding them in order for communication to happen.

Teacher’s and students’ metaphorical sentences go in opposite directions. The teacher wants to nurture and care for the group by bringing them together. In their letters, the students mentioned that they would prefer to study in groups, even though their metaphors seem to emphasize solo activities. In the interview, the teacher mentions the following:

I have never noticed a kind of group union that enhances learning… they may get together during the break, but it is not like the other group (Bas2A2); they exchange materials and are there for one another, even though they don’t study together. We have a great relationship and even grab a snack as a group sometimes. However, this group (Bas1A2) never shows enthusiasm when I ask them to share materials with a classmate that missed a class… (T1Exp6M)

It is possible to observe the effort on the part of the teacher to nurture the students from this group. The students, however, do not seem to show the same level of enthusiasm and effort to learn the language.

Table 4: Teacher’s and students’ metaphors – A2.2 group

Note. Teacher's and student H's metaphors and explanation sentences have been translated by the author.

This is the group that allows the teacher to ‘cook with more ingredients’, and therefore, he is able to take better care of his students, offering them a variety of options in the classroom. The students’ metaphorical sentences reflect effort; even though their metaphors refer to individual effort, their letters demonstrate that they need one another throughout the learning process. Doing gymnastics, running a marathon, learning to drive, and, above all, the baby's first steps are individual efforts, but having somebody else’s help, support, and motivation is crucial.

These students have a clear idea of what their language learning beliefs are, and all of them share the common goal of being able to communicate orally, which is a barrier that the group as a whole is working on overcoming; the teacher understands their need – achieving fluency is a goal that the teacher himself shares with them – and emphasizes such practice in the classroom.

During the interview, the teacher explained that he offers this group a great deal of auditory input in order for them to be exposed to the target language and able to start producing language without being afraid of making mistakes. The first twenty minutes of his classes are dedicated to spontaneous conversation because he wants students to internalize the language and make an effort to use it.

For this teacher, planning for the groups is a matter of perceiving their characteristics and adjusting his techniques accordingly:

It is a combination of what I consider to be useful and how they are used to doing in class so that it is not a very drastic change from one teacher to the next. It is a matter of perception and applying my techniques and seeing how they respond ... and I think it happens in the early stages of the year when I am getting to know the groups; then, it's like you already know what works with each group and what doesn't. So, if you see that after a few months they do not respond well, you have to find other techniques, maybe do more in-class work… (T1Exp6M)

However, during the interview with student E, she voiced her preference for doing extra writing pieces since she believes she expresses herself better this way. Even though the possibility of producing more compositions than the two for each unit of the book was not discussed with her teacher, it did not become a conflict.

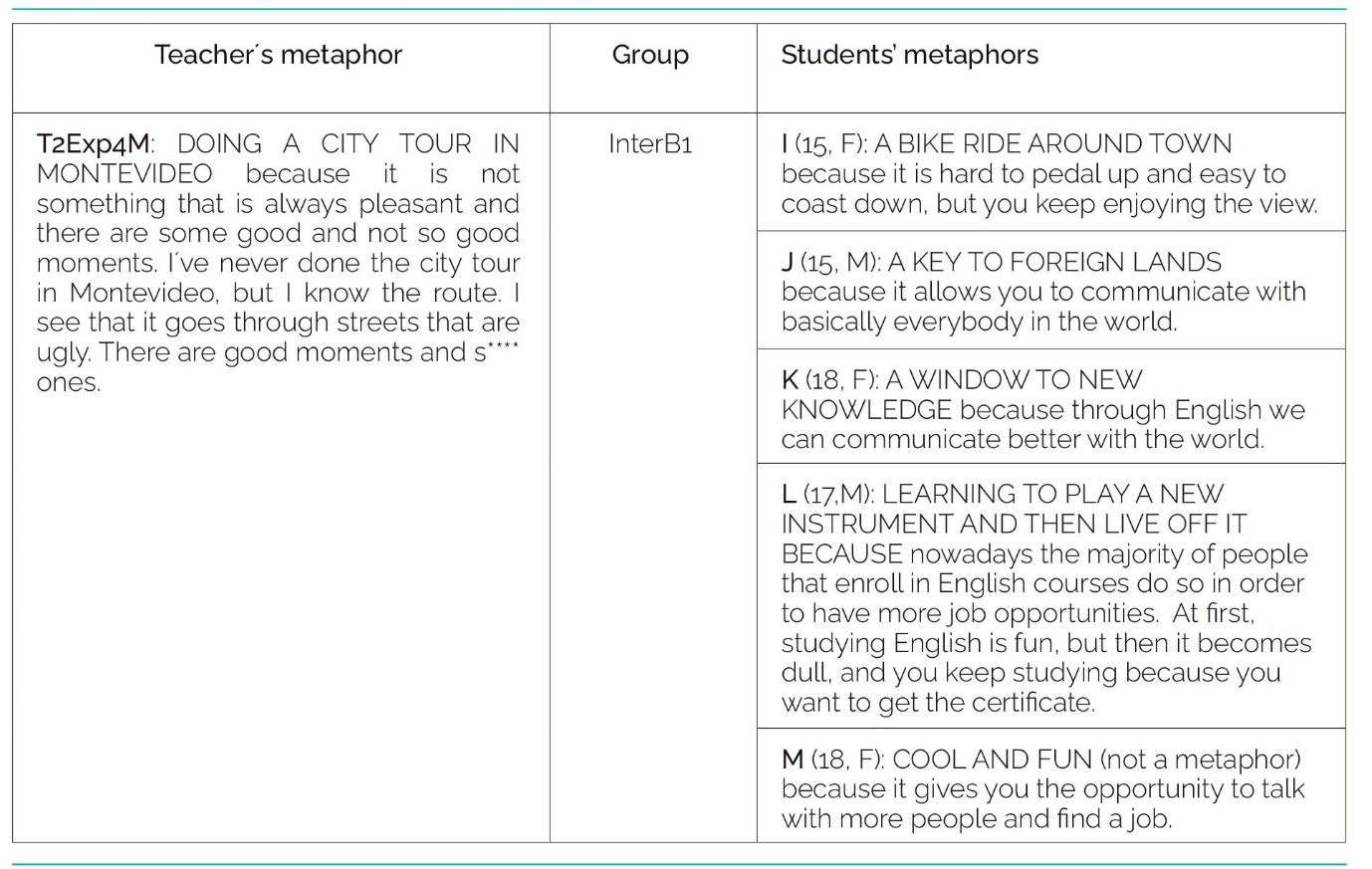

Case 2 –Teacher T2Exp4M, Group InterB1

Table 5: Teacher’s and students’ metaphors – B1 group

Note. The metaphors and the explanation sentences have been translated by the author.

Classes are a mix of enjoyable moments and not so enjoyable ones; the same holds true for city tours. A city tour is a short bus excursion where tourists visit beautiful parts of a city. However, for the bus to reach the attractive places, it has to pass through less beautiful streets that are not worth taking pictures of or paying attention to. City tours are the same for all those interested in visiting a particular place. When applying the metaphor to the classroom context, it is possible to translate it into offering the same type of class for all students who reach a certain level; also, the less proficient language classes would represent the ‘less attractive’ aspects to this teacher since he seems to enjoy working with higher levels of proficiency, as it was inferred during the interview.

Most of the students’ metaphorical sentences are focused on making discoveries. Student I mentions a bike ride in the city, which implies some labor when pedalling up a hill, but is also connected to the idea of discovering places when visiting a new city; however, when going on a bike ride to visit new places, the tendency is to avoid hills. Other metaphors (students J and K) are related to exploring new places with unique opportunities. Student L’s metaphor, on the one hand, may be related to learning something new (such as a musical instrument). However, on the other hand, it is more connected with the idea of making an effort to master a certain skill; this is confirmed in his letter in which he mentions that it is necessary to be in constant contact with the language, make vocabulary lists, and use monolingual dictionaries.

This group aims to take the Cambridge international exam, B1 Preliminary. For the teacher, the groups that are preparing for international exams tend to have a lower performance in general than other groups that are not sitting exams:

The thing about groups that are taking international exams is that there is always the tension between learning English and passing the exam, which is not the same. I am positive that it is not the same. I’m not criticizing such exams because they do fulfill a purpose, but they also play against us. So, there is tension ... I think that some tension is good. There are students who study to pass the exam and others who prefer to talk more, learn new words, do other types of activities, even grammatical activities that are not exam format. (T2Exp4M)

In general, the teacher focuses more on exam preparation toward the end of the school year. However, some students ask him for more exam practice to feel confident. During the school year, the teacher put great emphasis on memorizing vocabulary through spaced repetition. At the beginning of the classes, they always review what they did in the previous class. In addition, he allows students to work in pairs to do exercises and mainly to compare their answers and learn from their peers.

The teacher commented that he does not think much about varied LLS for different groups because, for him, certain aspects are intuitive:

I don’t sit down and think about what I’m going to do with each group specifically. I think certain things are more intuitive and I don’t think about them so much. But how deep we’ll discuss the topics will depend, in my opinion, on the relationship between the students, right? It will also depend on their language level… (T2Exp4M)

According to the teacher, factors such as age, level of English, and interests end up limiting the topics discussed in class. The teacher also mentioned during the interview that the textbook used in class presents topics that suit older students better. For some reason, even though the teacher made an effort to adapt the materials to his students’ tastes, he found it difficult to understand this group and generate empathy:

I failed to understand them all year, I couldn’t figure out where they were going, so the classes were more general … it’s not that I don’t like this group very much, but that you always have a group that you like more than the rest, naturally. This group did not generate good chemistry among themselves; it is a group that has 14-year-old boys and a 25-year-old woman. But anyway, it’s like ... it’s weird. I don’t know how to explain it to you... (T2Exp4M)

This teacher did not fully understand his group. He uses the metaphor of the city tour to describe his work. This image refers to the idea of a global vision of a city which does not interact much with its inhabitants; it is like being on the outside looking in. His opinion about the group might be influenced by the idea that students are coming to class with the sole purpose of passing the exam. It is also transparent that he has a preference for more advanced classes, which allow him to do in-class work using authentic materials, such as magazine and newspaper articles.

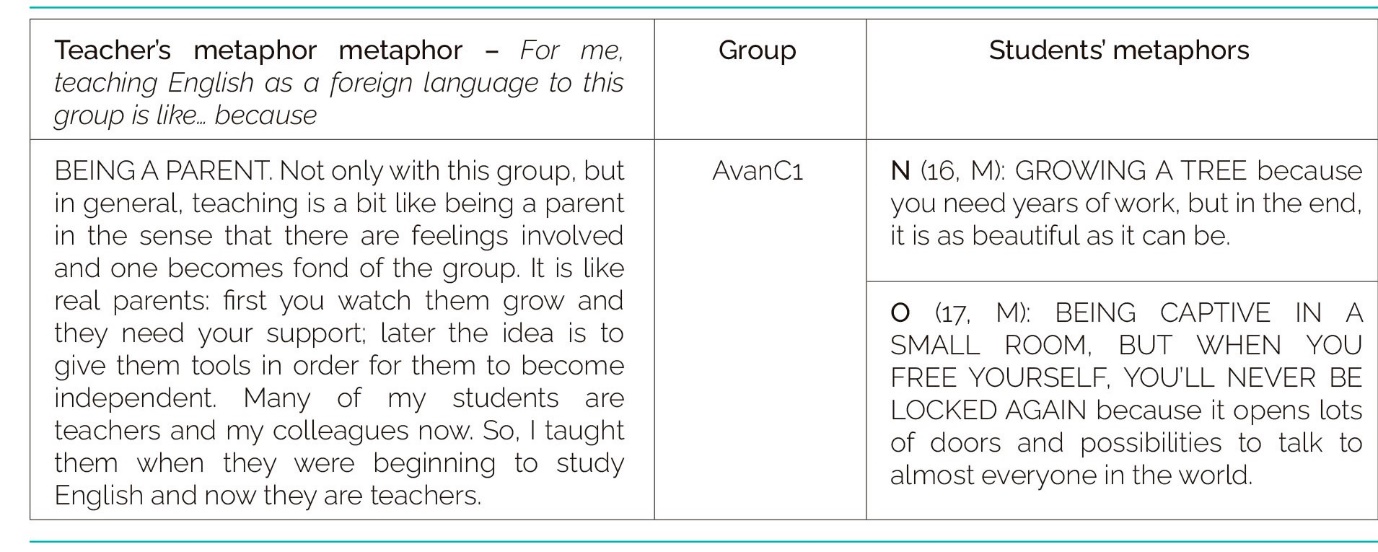

Case 3 – Teacher T3Exp14F, group AvanC1

Table 6: Teacher’s and students’ metaphors – C1 group

Note. Teacher's metaphor explanation sentence has been translated by the author

This teacher’s metaphor is summarized in the idea of nurturing; parents take care of their children and also have to educate them. In general, parents are proud of their children and their accomplishments. However, some parents have the tendency to overprotect their kids, while others embrace the philosophy of raising their children to be more independent and fend for themselves. Children, in turn, never forget the parents they had.

In this group, two trends are observed: nurturing care and seeking independence. As expressed by student N, the idea of growing a tree is related to nurturing care; in contrast, the prison metaphor by student O allows us to draw a parallel with parents who are very overprotective and steal their children's independence. However, when such kids manage to free themselves, they are unlikely to let themselves be dominated again by their families.

This teacher nurtures her group by ensuring that the students are learning English in a meaningful way and preparing to sit the international exam. The pressure to pass the test is present, mainly due to its high cost, but for her, passing would be evidence of learning. "My classes are not very exam-oriented - because I do not like the idea of learning the mechanics of the exam; I want them to learn, and if they learn, they will pass the exam" (T3Exp14F).

When asked if she adapted LLS to the group as a whole, or to each student, she replied:

To the student! Although I address the group as a whole, it is important to clarify to the students that they should make use of what is useful to each and every one of them, otherwise we keep looking for more suitable LLS. Sometimes the students say “I didn’t have enough time” or “this is not useful to me” and then we brainstorm what other things we can do. (T3Exp14F)

This teacher explained that she detects what students need, so she presents them with different strategies that may be useful to them; i the students decide which ones serve them according to their learning characteristics. Therefore, we observe that meaningful learning is the teacher’s goal, but the international exams have strongly influence the class.

Conclusions

Discussing language learning beliefs is vital for EFL teachers and students alike; it should be clear what everyone's expectations, intentions and objectives are about learning a foreign language. Beliefs prove to be an invisible but very present aspect in the classroom - much like an iceberg. The submerged part represents these beliefs, which seem to be in constant negotiation between teachers and students; in turn, the visible part is the interactions in the classroom. As evidenced in this research, metaphors offer an indirect way to assess and understand what students think and believe. Likewise, teachers can use metaphors to reflect on their own perceptions of their groups.

This research indicated that it is the teacher who makes the decisions for their group, considering many factors such as their beliefs, previous experiences and studies. On the other side, when part of the syllabus, international exams play a major role in how teachers plan their in-class work. All the participating teachers are clear about their beliefs and actions in class. It is shown that knowing the group in-depth allows teachers to select language learning strategies that best suit their class. This would also help improve the bond formed between the teacher and the students and among the students themselves.

We hope this paper might help teachers by offering them an opportunity to reflect on their beliefs and realize that their students also come to class with their own. Also, we expect this paper to demonstrate to the research community that using conceptual metaphors is possible to begin to explore what teachers and students think, offering a form of expression to synthesize and externalize complex thoughts.

Nota:

Aprobación final del artículo: Dra. Verónica Zorrilla de San Martín, editora responsable de la revista.

Contribución de autoría:

La única autora fue responsable de la concepción del trabajo, diseño de la investigación, recolección de datos, procesamiento, análisis, elaboración y corrección del documento.

References

Armstrong, S.L. (2015). Retrospective metaphor interviews as an additional layer in elicited metaphor investigations: bridging conceptualizations and practice. In W. Wan & G. Low (Eds.), Elicited metaphor analysis in educational discourse (pp. 119-138). John Benjamins.

Barcelos, A. M. F. (2000). Understanding teachers' and students' language learning beliefs in experience: A Deweyan approach (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). The University of Alabama.

Barcelos, A. M. F. (2003a). Researching beliefs in SLA: A critical review. In P. Kalaja & A.M.F. Barcelos (Eds.), Beliefs About SLA: New Research Approaches (pp. 7-33). Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Barcelos, A. M. F. (2003b). Teachers’ and students’ beliefs within a Deweyan framework: Conflict and influence. In P. Kalaja & A.M.F. Barcelos (Eds.), Beliefs about SLA: New Research Approaches (pp. 171-199). Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Barnard, R., & Burns, A. (Eds.). (2012). Researching language teacher cognition and practice: International case studies (New Perspectives on Language and Education). Multilingual Matters.

Borg, S. (2003). Teacher cognition in language teaching: A review of research on what language teachers think, know, believe, and do. Language Teaching, 36(2), 81-109.

Cameron, L., & Low, G.D. (1999). Metaphor. Language Teaching, (32), 77-96.

Dufva, H. (2003). Beliefs in dialogue: a Bakhtinian view. In P. Kalaja & A.M.F. Barcelos (Eds.), Beliefs about SLA: New Research Approaches (pp. 131-151). Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Ellis, R. (2008). Learner beliefs and language learning. ASIAN EFL Journal, 10(4), 7-24.

Fang, S. (2015). College EFL learners’ metaphorical perceptions of English learning. The Journal of Asia TEFL, 12(3), 61-79. http://dx.doi.org/10.18823/asiatefl.2015.12.3.3.61

Flick, U. (2015). El diseño de la investigación cualitativa. Morata.

Freeman, D. (2002). The hidden side of the work: Teacher knowledge and learning to teach. A perspective from North American educational research on teacher education in English language teaching. Language Teaching, 35(1), 1-13.

Hernández Sampieri, R. (2014). Metodología de la investigación. Mac Graw Hill.

Horwitz, E. K. (1985). Using student beliefs about language learning and teaching in the foreign language methods course. Foreign Language Annals, 18, 333-340.

Horwitz, E. K. (1988). The beliefs about language learning of beginning university foreign language students. The Modern Language Journal, 72(3), 283-294.

Hosenfeld, C. (2003). Evidence of Emergent Beliefs of a Second Language Learner: A Diary Study. In P. Kalaja & A. M. F. Barcelos (Eds.), Beliefs about SLA: New Research Approaches (pp. 37-54). Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Johnson, K. E. (1995). Understanding communication in second language classrooms. Cambridge University Press.

Kalaja, P., Barcelos, A. M. F., Aro, M., & Ruohotie-Lyhty, M. (2015). Beliefs, agency and identity in foreign language learning and teaching. Palgrave Macmillan.

Lakoff, G. (1993). The Contemporary Theory of Metaphor. In A. Ortony (Ed.), Metaphor and thought. (2nd ed., pp. 202-251). Cambridge University Press.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (2003). Metaphors we live by. Afterword. University of Chicago Press.

Low, G. (2015). A practical validation model for researching elicited metaphor. In W. Wan & G. Low (Eds.), Elicited metaphor analysis in educational discourse (pp. 15-37). John Benjamins.

Marrero, J., Rodríguez, A., & Rodrigo, M. J. (1993). Las teorías implícitas: una aproximación al conocimiento cotidiano. Visor.

Seung, E., Park, S., & Jung, J. (2015). Methodological approaches and strategies for elicited metaphor-based research: a critical review. In W. Wan & G. Low (Eds.), Elicited metaphor analysis in educational discourse (pp. 39-64). John Benjamins.

Soriano, C. (2012). La metáfora conceptual. In I. Ibarretxe-Antuñano & J. Valenzuela (Eds.), Lingüística Cognitiva (pp. 87-109). Anthropos.

Stake, R. E. (1999). Investigación con estudio de casos. Morata.

Wan, W., & Low, G. (2015). Introduction. In W. Wan & G. Low (Eds.), Elicited metaphor analysis in educational discourse (pp. 1-12). John Benjamins.

Wan, W. (2015). Developing critical thinking in academic writing through a metaphor elicitation technique: an exploratory study. In W. Wan & G. Low (Eds.), Elicited metaphor analysis in educational discourse (pp. 213-237). John Benjamins.

Zambon, N. (2019). ¿Qué piensan los docentes y los estudiantes del aprendizaje del inglés como lengua extranjera?: un estudio sobre creencias a partir de la metáfora conceptual. Unpublished master's thesis. Universidad ORT Uruguay. Sistema de Bibliotecas de la Universidad ORT Uruguay. https://dspace.ort.edu.uy/bitstream/handle/20.500.11968/4020/Material%20completo.pdf?cv=1&isAllowed=y&sequence=-1

![]()

Artículo publicado en acceso abierto bajo la Licencia Creative Commons - Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)