Note. Modified from Perales-Escudero et al. (2021).

Reading comprehension beliefs of Mexican pre-service language teachers: a Likert scale study

Creencias lectoras de profesores de idiomas en formación mexicanos: un estudio Likert

Crenças leitoras de professores de línguas em formação mexicanos: um estudo Likert

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.18861/cied.2023.14.2.3375

Moisés

Damián Perales-Escudero

Universidad Autónoma del Estado de

Quintana Roo

Mexico

mdperales@uqroo.edu.mx

ORCID:

0000-0001-6279-1520

Mizael

Garduño Buenfil

Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Quintana

Roo

Mexico

mgarduno@uqroo.edu.mx

ORCID:

0000-0003-2181-1585

Vilma

Esperanza Portillo Campos

Universidad Autónoma del Estado de

Quintana Roo

Mexico

vportillo@uqroo.edu.mx

ORCID:

0000-0002-5738-4952

Received:

December 13, 22

Approved: February 9, 23

How

to cite:

Perales-Escudero,

M. D., Garduño Buenfil, M., & Portillo Campos, V. E. (2023).

Reading comprehension beliefs of Mexican pre-service language

teachers: a Likert scale study. Cuadernos

de Investigación Educativa,

14(2).

https://doi.org/10.18861/cied.2023.14.2.3375

Abstract

This paper aims to report the adaptation of a new version of the Scale of Implicit Theories of Reading Comprehension (ETICOLEC as per its Spanish acronym) with a sample of 77 randomly chosen English majors at a peripheral campus of a small university in the Southeast of Mexico. The ETICOLEC Likert scale was originally designed to measure the reading comprehension beliefs of middle school teachers of several subjects. Hence, it was necessary to adapt it to identify the beliefs of pre-service language teachers. A standard procedure recommended by the literature (Prat & Doval, 2005) was used to add new items to the scale and test its psychometric properties using principal component analysis and internal consistency analysis with Cronbach´s alpha. Calculations were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, v. 26). As with the original ETICOLEC, this adapted version yielded five internally consistent sub-scales, albeit slightly different from the original ones. Each subscale measures an implicit theory or group of beliefs about reading comprehension. As a secondary, exploratory goal, we also describe the participants according to their implicit theories. Most participants held implicit theories that are functional for the kinds of epistemic reading tasks required by their university education. However, a large minority did not appear to hold any firm beliefs about reading, suggesting insufficient exposure to various complex reading tasks and genres. This situation must be addressed to ensure these pre-service teachers become effective reading teachers.

Keywords: reading comprehension, beliefs, pre-service teachers, language teachers, Likert scales.

Resumen

Este trabajo persigue reportar la adaptación de una nueva versión de la Escala de Teorías Implícitas de la Comprensión Lectora (ETICOLEC) con una muestra de 77 estudiantes de una licenciatura en enseñanza del inglés, elegidos al azar en un campus periférico de una universidad pública pequeña del sureste de México. La ETICOLEC es una escala tipo Likert que fue originalmente diseñada para medir las creencias sobre la comprensión lectora de profesores de secundaria de varias materias. Por lo tanto, se hizo necesario adaptarla para identificar las creencias lectoras de profesores de lenguas en formación. Se siguió el procedimiento de Prat y Doval (2005) para añadir nuevos ítems a la escala y verificar sus propiedades psicométricas usando análisis de componentes principales y de consistencia interna de cada subescala con alfa de Cronbach. Las estadísticas se computaron usando el software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, v. 26). Como en la ETICOLEC original, esta versión adaptada arrojó cinco subescalas con buena consistencia interna, aunque ligeramente distintas de las originales. Cada una mide una teoría implícita o grupo de creencias sobre la comprensión lectora. Como objetivo secundario y exploratorio, describimos las teorías implícitas presentes en la muestra. La mayoría de los participantes se adhirieron a teorías implícitas funcionales para las tareas de lectura epistémica requeridas en su formación universitaria. Sin embargo, una minoría considerable pareció no sostener ninguna creencia firme sobre la lectura. Ello sugiere una participación insuficiente en una variedad adecuada de géneros y tareas de lectura complejas. Esta situación debe atenderse para mejorar las posibilidades de que estos docentes sean capaces de enseñar comprensión lectora de manera eficaz.

Palabras clave: comprensión lectora, creencias, profesores en formación, profesores de lenguas, escalas tipo Likert.

Resumo

Este trabalho tem como objetivo relatar a adaptação de uma nova versão da Escala de Teorias Implícitas de Compreensão de Leitura (ETICOLEC) com uma amostra de 77 alunos de uma licenciatura em ensino de inglês eleitos ao azar em um campus universitário de uma universidade pública pequena do sudeste do México. O ETICOLEC é uma escala do tipo Likert que foi originalmente projetada para medir as crenças dos professores do ensino médio sobre a compreensão da leitura em várias disciplinas. Portanto, tornou-se necessário adaptá-la para identificar as crenças de leitura de professores de línguas em formação. O procedimento de Prat e Doval (2005) foi seguido para adicionar novos itens à escala e verificar suas propriedades psicométricas usando análise de componentes principais e análise de consistência interna de cada subescala com alfa de Cronbach. As estatísticas foram computadas usando o software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, v. 26). Assim como no ETICOLEC original, esta versão adaptada gerou cinco subescalas com boa consistência interna, embora ligeiramente diferentes das originais. Cada um mede uma teoria implícita ou um conjunto de crenças sobre a compreensão da leitura. Como objetivo secundário e exploratório, descrevemos as teorias implícitas presentes na amostra. A maioria dos participantes aderiu a teorias implícitas funcionais para as tarefas de leitura epistêmica exigidas em sua educação universitária. No entanto, uma minoria considerável parecia não ter uma crença firme sobre a leitura. Isso sugere participação insuficiente em uma variedade apropriada de gêneros e tarefas de leitura complexas. Esta situação deve ser abordada para melhorar as chances de que esses professores sejam capazes de ensinar a compreensão da leitura de forma eficaz.

Palavras-chave: compreensão de leitura, crenças, professores em formação, professores de línguas, escalas Likert.

Introduction

The study of pre-service teachers as readers is an area of interest in Mexico due to the continuous unsatisfactory results of Mexican students in reading comprehension tests. It stands to reason that if pre-service teachers are good readers, this increases their chances of being good reading teachers. At the same time, if pre-service teachers are not good readers, it behooves universities to diagnose their reading difficulties and implement solutions. Previous studies point in the direction that some teachers do not have strong reading habits or well-developed ideas about teaching, while others do (Asfura & Real, 2019; Elche-Larrañaga & Yubero-Jiménez, 2019).

This interest in the connections between teachers and readers has led scholars to focus on teachers’ ideas about reading. These ideas are individual differences in their cognition about reading that are important to research (Vansteelandt et al., 2017). This is because teachers with more sophisticated cognition about reading can, in turn, positively influence their future students’ reading comprehension and overall learning (Makuc, 2020).

Teachers’ thinking has been widely studied due to its relevance in understanding teachers’ orientations and actions (Borg & Santiago-Sánchez, 2020). Such understandings can lead to interventions that improve teaching. Teachers’ thinking has been researched using several theories and methods. For example, Munita (2013) implemented life stories and interviews to characterize the beliefs, representations, and knowledge (BRK) held by Spanish teachers. The study revealed a belief held by good readers in the usefulness of literary reading for building identity through life lessons learned from texts. For good readers, it was important to establish connections across texts or intertextuality. Weak readers alluded mostly to feeling excited about the plot and to retrieving isolated information.

Errázuriz et al. (2019) focused on Chilean teachers’ conceptions of reading. They classified conceptions into reproductive ones and epistemic ones. Teachers with reproductive conceptions established utilitarian goals for their reading and used text-centered strategies. Like Munita’s (2013) strong readers, teachers with epistemic conceptions drew connections between reading, identity development, and aesthetic pleasure. Another construct used to investigate reading beliefs is that of implicit theories (ITs). ITs are “representations that the reader has developed about reading and which he or she applies unconsciously to the task; hence, these representations mediate the relationship between reader and text” (Lordán et al., 2015, p. 39). In a different study that used Lordán et al. (2015) ITs questionnaire, Errázuriz et al. (2020) found a mix of epistemic and reproductive ITs in Chilean teachers. The epistemic ITs were more common among language teachers and less common among teachers of other subjects.

Perales-Escudero et al. (2021) focused on the ITs held by in-service Mexican middle school teachers of several subjects in two border states. Using the ETICOLEC scale, they found that teachers hold well-defined ITs about reading, but most teachers hold the least sophisticated reproductive ITs. An exception was teachers of Spanish and English, who tended to adhere to the more sophisticated, epistemic ITs.

Specifically for Mexican pre-service teachers of English as a Foreign Language (EFL), three studies have been conducted. Moore & Narciso (2011) interviewed 15 English majors. Consistently with the literature above pointing to more sophisticated beliefs in language teachers, their participants tended to adhere to complex, transactional beliefs. Similarly, Perales-Escudero et al. (2017) interview study identified that English majors’ reading beliefs tended to become more sophisticated and differentiated as they progressed in their studies.

Perales-Escudero et al. (2022) conducted a quantitative study with 222 first-year, pre-service EFL teachers using the ETICOLEC scale. They found an -encouraging- high occurrence of the more sophisticated beliefs. Also encouraging was the absence of purely receptive beliefs as receptive beliefs blended with more complex ones. Nevertheless, they also found that about a fifth of their participants did not hold any beliefs about reading comprehension. A limitation of Perales-Escudero et al. (2022) was that some subscales of the ETICOLEC did not achieve high internal consistency. This finding contrasts with the high consistency achieved for the same scale but with a different, in-service teacher population of several subject matters in Perales-Escudero et al. (2021). This divergence points to a need to adapt the scale for the specific reading beliefs of pre-service teachers. Hence, the study reported here sought to validate an adapted version of the ETICOLEC scale (Perales-Escudero et al., 2021) with a sample of pre-service EFL teachers enrolled in a BA in English Language Teaching (ELT) at a small public university in Southern Mexico. The ultimate goal is to have a valid instrument to describe the reading beliefs of larger groups of pre-service language teachers in connection with other variables such as year of studies, gender, and socioeconomic condition. These variables are not explored here due to the study’s purpose to validate an adapted version of the ETICOLEC and its small sample size. However, like Perales-Escudero et al. (2021), we do describe the ITs present in the sample in an exploratory manner because doing so contributes to showing the scale’s empirical usefulness, thus enhancing its validity.

Theoretical

framework

It is important to investigate beliefs about reading comprehension because such beliefs impact reading performance (Schraw & Bruning, 1996, 1999; Schraw, 2000) and ways to teach reading (Mo, 2020). ITs as a theoretical construct are often used to describe students’ and teachers’ ideas about reading. ITs are groups of implicit representations about an aspect of reality or groups of beliefs. Their nature is social in that individuals develop them by participating in specific sociocultural settings. They are also personal because individuals hold them in their minds even if they are unaware of them. Individuals use ITs to make sense of the social situations they face in the lifeworld (Pozo et al., 2006; Rodrigo, 1997; Rodrigo & Correa, 2001; Rodríguez & González, 1995).

As established in Marrero Acosta (2009), Rodríguez Zedán (2000-2001), and Jiménez Llanos (2009), teachers’ ITs consist of a mixture of personal beliefs, pedagogical knowledge, and societal thinking about education. Teachers' ITs about different aspects of learning and teaching focus on resolving teaching problems and shaping teachers' pedagogical styles. Teachers develop their ITs from different societal sources. Among them are the apprenticeship of observation, socially shared ideas about education, formal teacher education, and the culture of the specific school(s) where they work or learn how to teach. For pre-service teachers, the programs where they are formally trained function as the proximal contexts of reference for the development of ITs. This is because they participate in specific discourses about reading and specific reading tasks that may vary across programs (Perales-Escudero et al., 2021). This variation can lead to the emergence of shared ITs among groups of pre-service teachers, which might, in turn, be different from those ITs of pre-service teachers enrolled in different programs.

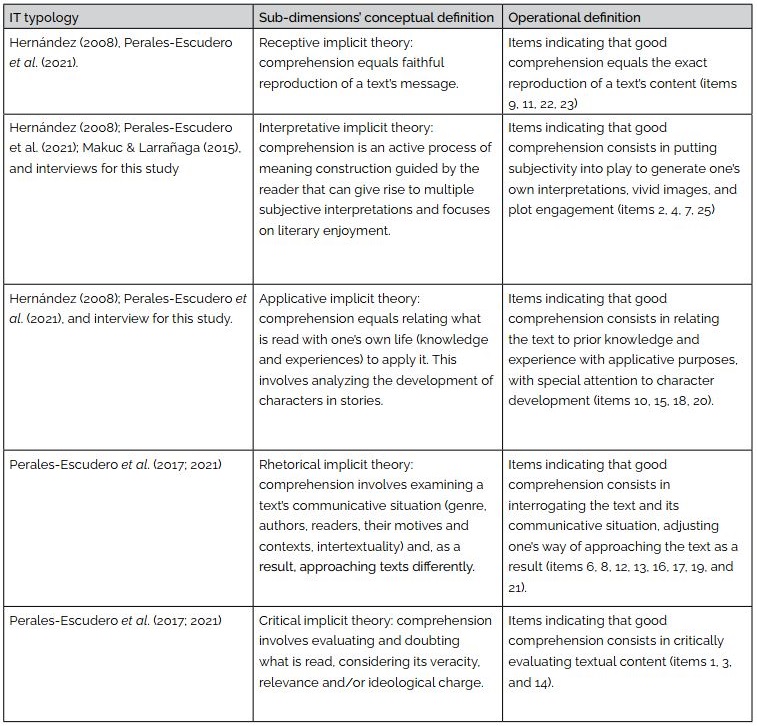

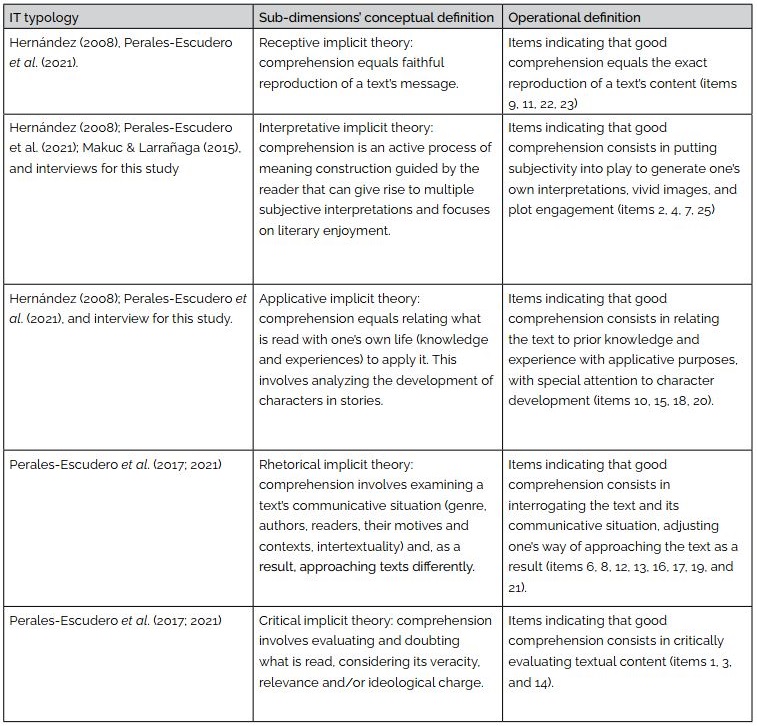

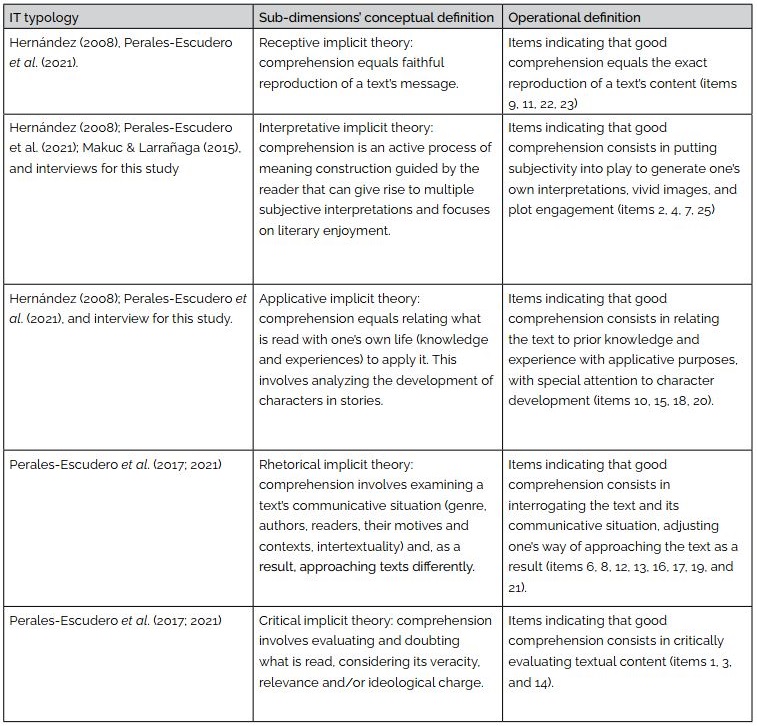

Reading ITs have been explored using different theoretical approaches and instruments. Some studies have used Likert scales (Makuc & Larrañaga, 2015; Lordán et al., 2015), and others have used interview protocols (Hernández, 2008; Moore & Narciso, 2011; Perales-Escudero et al., 2017). In general, they rely on and find a three-part taxonomy of ITs.

The nature of each taxonomy and the specific names given to the ITs tend to differ in each study. Nevertheless, commonalities exist. In general, they have found simpler ITs (called receptive, reproductive, or linear) and more complex ones. The simpler ones refer to understanding reading as a text-based reproduction of content. The more complex ones (called epistemic, transactional, constructive, or literary) show more variation. They entail more strategic and critical approaches (Hernández, 2008; Lordán et al., 2015; Perales-Escudero et al., 2017), application of the reading material to one’s life to reflect on and build identity (Hernández, 2008; Makuc & Larrañaga, 2015; Perales-Escudero et al., 2017), an emphasis on intertextuality (Perales-Escudero et al., 2017, 2021), or entertainment (Makuc & Larrañaga, 2015).

The ETICOLEC model is slightly different in that it found 5 ITs (Perales-Escudero et al., 2021). In the Receptive IT, comprehension equals faithful reproduction of a text’s message. For the Interpretive IT, comprehension is an active process of meaning construction guided by the reader that can give rise to multiple subjective interpretations. The Applicative IT sees comprehension as relating what is read with one’s own life (knowledge and experiences) to apply the former to the latter. For the Rhetorical IT, “comprehension involves examining a text’s communicative situation (genre, authors, readers, their motives and contexts, intertextuality) and approaching texts differently as a result” (Perales-Escudero et al., 2021, p. 25). These reading beliefs correspond to rhetorical reading as defined by Haas and Flower (1988) but fall under the purview of critical reading, according to Cassany (2003). Perales-Escudero et al. (2021) used the label “rhetorical” instead of “critical” because, for the participants in that study, “critical” meant something somewhat different than what was intended by Cassany (2003). For the Critical IT, “comprehension involves evaluating and doubting what is read, considering its veracity, relevance and/or ideological bias” (Perales-Escudero et al., 2021, p. 25). Since the items were grouped differently than the rhetorical ones by the statistical analyses, this label and the distinction between rhetorical and critical ITs held ecological validity.

Methods

This scale adaptation and validation study follows Prat and Doval's (2005) scale development procedure. We randomly selected 77 English majors enrolled in different semesters of the BA in English Language Teaching at a very small public university in Southern Mexico. 31 were men, and 46 were women. Ages ranged between 18-21 years old. The simple surpasses the minimum number of three respondents per item established by Prat and Doval (2005), whose procedure was used to build and validate the original ETICOLEC and this modified version. This procedure involves five phases, described below.

1. Delimitation of the scale’s goals

The goal of the scale was delimited to elicit the ITs about reading comprehension of ELT majors. Other types of ITs were excluded. This was done through meetings with the authors and other research team members early in the Spring of 2022.

2. Item and measuring instrument development

Items were developed from the ETICOLEC and the analysis of semi-structured interviews with 10 ETL majors of the same university as those of the target population. The interviews allowed us to include the perspectives of the target population. The interviews were conducted by the co-authors and an assistant in the Spring of 2022 on Microsoft Teams ©. Two assistants then transcribed them, and the co-authors analyzed them using qualitative content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). These interviews were relevant due to the culturally-situated nature of ITs. Next, the research team drafted an initial list of items and a Likert-type scale of answers per level of agreement in late Spring of 2022.

3. Theoretical selection of items

In the Summer of 2022, we proceeded to an initial classification of the items in subscales according to the ETICOLEC, the interviews, and the findings in Perales-Escudero et al. (2017), a study carried out with Mexican ELT majors (see Table 1 and Appendix 1 with the full instrument). The main change to the previous version of the ETICOLEC was the addition of items 2, 4, and 25 to the interpretative subscale. These items focus on beliefs about literary pleasure, like imagining what’s going on in a story, getting involved in the plot, and feeling excited about the developments in the story. Another change was the addition of question 18 to the applicative scale. This question asks whether students think that good comprehension involves examining characters’ narrative arc of personal growth across a story. We added this question to this scale rather than the interpretative one since analyzing characters’ development evinces a more advanced kind of reading that connects with readers’ own identity (Munita, 2013). These are features of the Applicative IT. These changes were validated using the judgments of five experts and the Content Validity Index (CVI; Wynd et al., 2003). The CVI is a quantification of the judgments of context experts. We used two criteria for the experts to follow: the item's relevance of the item for a subscale and the match of an item to the intended subscale. As in Lordán et al. (2015), we only preserved items with a CVI greater than .7.

Table

1

The

original design of the subscales

Note.

Modified from Perales-Escudero et

al.

(2021).

The

modified ETICOLEC scale was administered in the participants’

native language, Spanish (Appendix 1). An English-language version

can be found in Appendix 2.

The scale asks students to read 25 items that complete the statement “I believe effective reading comprehension involves...” For each item, they must choose between 1 (strongly disagree) and 5 (strongly agree) to show their level of agreement or disagreement with the resulting proposition. For example, item 17 would be read as “I believe effective reading comprehension involves contrasting the message of the text with those of other related texts.” A respondent who chooses options 4 (agree) or 5 (strongly agree) shows adherence to this belief, which is a part of the Rhetorical IT. By contrast, a respondent who chooses a number between 1 and 3 is not considered to hold this belief. It is important to note that, unlike other implicit theory instruments, the ETICOLEC does not elicit beliefs about texts' functions or readers' roles. Therefore, its usefulness is restricted to exploring readers’ beliefs about comprehension itself. Of course, participants’ ideas about readers’ processes can be inferred from their answers, but they are not the main focus of the ETICOLEC.

4. Empirical selection of items

The data was collected by transcribing the revised version of the ETICOLEC scale into a Google Forms © document. The form also contained an informed consent section where students were asked to write their names to show their agreement to participate in the study. The co-authors obtained and sent a link to the participating students via email. This was done in the Summer of 2022.

5. Evaluation of psychometric properties

We analyzed the validity and reliability of each subscale through Cronbach’s alpha and principal component analysis with Varimax rotation using SPSS v. 26. This was done in the Fall of 2022.

As a final, additional phase, we described the participants’ ITs and their combinations or schemas (Ghaith, 2021). We did this following the same method used in the study that validated the original ETICOLEC scale (Perales-Escudero et al., 2021). The participants’ scores for each IT were calculated into new variables so that the participants who chose 4 (agree) and 5 (strongly agree) for most items within a subscale (implicit theory) were classified as holding that implicit theory and assigned a number accordingly, thus creating new variables, one per each IT. Then, using those figures for IT variables, a new variable was calculated to capture the participants’ schemas or combinations of more than one implicit theory. Although this description of the ITs and schemas in the sample is not part of the validation per se, it is useful to show the applicability of the modified ETICOLEC, which, in the end, enhances its validity. This exploratory procedure has been followed in previous validation studies (Perales-Escudero et al., 2021).

Results

and Discussion

Reliability

and exploratory principal component analyses

The Keiser-Meyer-Olkin sample adequacy test showed that the sample was adequate for the subsequent analyses (KMO=0.760). Values larger than .6 are considered acceptable for samples smaller than 100 (Shreshta, 2021), like ours. Likewise, the data meet the assumption of sphericity as determined by a Bartlett test (Χ2=863.09, p<.000). We ran an exploratory, principal component analysis with Varimax rotation, followed by a confirmatory analysis also with Varimax rotation. After defining the components (implicit theories), we estimated each one’s reliability. Table 2 shows that the items coalesced in components that generally matched our model. Every subscale showed good reliability. Appendix 1 contains the full instrument.

Table

2

Factorial

analysis and internal consistency of each subscale

The

most significant change regarding the original taxonomy was the

dispersion of several beliefs that originally clustered under the

Rhetorical

IT

(items 6, 12, 16, and 21) and one pertaining to the Critical

IT

(item 3) into other ITs. This kind of divergence is unsurprising

since the original IT schema underlying the ETICOLEC was based on

in-service middle school teachers of courses as diverse as chemistry

and history. Due to their status as pre-service English teachers, our

participants are exposed to a different sociocultural context and a

specific school culture. It is well-known that ITs change along the

lines of sociocultural experiences and even concrete schools (Jiménez

Llanos, 2009). The following paragraphs describe the ITs found in the

sample.

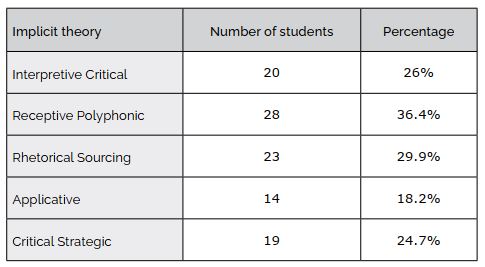

We chose the label “Interpretive-Critical” for the first IT emerging from the component analysis. This theory includes several beliefs of the original interpretive theory, such as thinking that good comprehension involves imagination, emotions, and subjectivity to guide understanding. However, it also includes critical ideas (per Cassany, 2003 and Perales-Escudero et al., 2021), such as thinking that good comprehension is about identifying authorial purposes and questioning ideologies. This implicit theory is thus functional for reading literary works critically since this activity involves both subjective pleasure and critical stances (Hintz & Tribunella, 2019).

We labeled the next IT “Receptive-Polyphonic.” The adjective “polyphonic” alludes to multiple voices or perspectives in texts, including the author’s implicit presence and messages (Tosi, 2017). All the beliefs of the Receptive IT are included here, as well as two rhetorical beliefs of a polyphonic nature. These are item 12, about discovering implicit messages, and item 21, about understanding multiple perspectives in a single text. Therefore, this IT holds that good comprehension involves being faithful to the text’s content, extracting main ideas, inferring implicit messages, and identifying different voices and perspectives in the text. The same IT had been previously found with pre-service language teachers at another university (Perales-Escudero et al., 2022). The Receptive-Polyphonic theory, therefore, appears to be typical of pre-service language teachers. It seems to stem from involvement with genres that include multiple perspectives and implicit premises, which are common in our field. It is thus functional for identifying multiple perspectives and implicit messages in single texts, which are important components of college-level reading comprehension (Barzilai & Weinstock, 2020).

The third IT is the Applicative one. This theory holds that good comprehension is about applying what is learned from texts to readers’ lives. This involves analyzing the personal growth of characters in stories and developing one's interpretations. It is thus a sophisticated literary theory found by Munita (2013) as it focuses on reading for identity development.

The fourth IT is Rhetorical Sourcing. The term “sourcing” refers to the examination of a text’s extratextual elements or “source” (Bråten et al., 2018; Londra et al., 2021), such as its author (item 8), the context of production (item 13), connections to other texts (item 17), and likely audience (item 19). Readers with this theory are likely to be good at sourcing or evaluating multiple documents based on this kind of information (Brante & Strømsø, 2018). Reading multiple documents using sourcing is a key university-level literacy and, in general, a relevant societal literacy considering readers’ need to evaluate information critically in contemporary society (Bråten et al., 2018). Then, the Rhetorical Sourcing theory holds that good comprehension entails finding information about a text’s source. A key difference between this IT and the Receptive Polyphonic theory (which also includes rhetorical beliefs) is that the latter focuses on intratextual rhetorical dimensions, i.e., multiple perspectives in single texts. The latter, by contrast, focuses on the extratextual rhetorical dimensions described above. These two ITs emerged as distinct points to differentiated experiences with multiple document comprehension versus multiple perspective comprehension in single texts among the participants and in their context.

We called the last IT the Critical Strategic theory. It includes two critical beliefs: good comprehension consists of questioning texts’ truthfulness, and good comprehension involves questioning texts’ relevance to the readers’ context. The belief that good comprehension involves adjusting reading strategies according to a text’s genre, originally grouped under the Rhetorical implicit theory, coalesced with those two critical items. This latter belief matches recent proposals about the relationship between readers’ strategic processes and the diverse semiotic features of different genres (Parodi et al., 2020.

Distribution

of ITs in the sample

In an exploratory manner, we present the distribution of the ITs in our sample. This is exploratory since the sample (n=77) does not represent the entire population (n=197).

Table

3

Distribution

of ITs to the participating students

Readers should note that the numbers in Table 3 do not add up to 77/100% because 30 participants held more than one IT. In Ghaith’s (2021) terms, they were multischematic. As shown in Table 3, the most prevalent IT is the Receptive Polyphonic one. This suggests that the participants’ context includes polyphonic texts and reading tasks that restrict subjective interpretations and require retrieval of multiple perspectives and implicit messages. Likewise, the Rhetorical Sourcing theory figures suggest that sourcing and multiple document comprehension are relatively common reading tasks in the context. In decreasing order are found the Interpretive Critical IT, the Critical Strategic IT, and the Applicative IT. Their less common occurrence suggests that literary reading and the kind of reading named critical here are not very prominent in the target context. It is also important to note that 30 participants (39%) did not score high in any of the ITs identified in this study. Adapting Ghaith’s (2021) terms, they were aschematic as they did not adhere to any IT. This may be due to insufficient exposure to a variety of genres and adequate reading tasks that would lead to the development of reading comprehension ITs of the kind tested by the ETICOLEC.

Conclusions

Students’ poor performance in reading comprehension has been a concern in the Mexican educational system for some time. Understanding the thinking of pre-service language teachers about reading is important to prepare them to be better teachers of reading. Previous studies have shown somewhat positive results with Mexican pre-service EFL teachers (Moore & Narciso, 2011; Perales-Escudero et al., 2017, 2022). However, the latter study also found that a relatively large minority of first-year ELT majors were schematic, not holding any IT. This might have been due to insufficient reading experiences in and out of school. The results of Perales-Escudero et al. (2022) also pointed to a need to refine the ETICOLEC by adapting it for pre-service EFL teachers.

The present study has validated an adapted version of the ETICOLEC, which has been found to be reliable for the target population. The items grouped in subscales of ITs are somewhat different from the original ETICOLEC. This can be explained by the different nature of the participants and the cultural context (Jiménez Llanos, 2009; Marrero Acosta, 2009). Nevertheless, they are consistent with the types of reading identified in the literature, such as sourcing for multiple document comprehension (Bråten et al., 2018; Londra & Saux, 2021), polyphonic reading or multiple perspective comprehension (Barzilai & Weinstock, 2020; Tosi, 2017), and literary reading. Previous IT studies had not addressed beliefs about sourcing or multiple perspective comprehension, which are important reading practices in contemporary education and society. Therefore, this scale is useful in identifying populations that may need to strengthen these pivotal reading practices.

A limitation of the study is the small sample size which, although sufficient for validation research, is not enough to arrive at firm conclusions about the population’s ITs. The description of ITs above is merely exploratory and should be taken with caution. The next step with the current, adapted version is to apply the ETICOLEC to larger groups of ELT majors and explore associations between ITs and other variables such as gender, socioeconomic status, reading performance, and the teaching of reading itself. Doing so is important to better prepare teachers to meet the complex demands of EFL literacy teaching in the twenty-first century.

Notes:

Final

approval of the article:

Verónica

Zorrilla de San Martín, PhD, Editor in Charge of the journal.

Authorship contribution:

Moisés Damián Perales-Escudero carried out the conception of scientific work. Data collection, interpretation, and analysis were in charge of Moisés Damián Perales-Escudero, Mizael Garduño Buenfil and Vilma Portillo Campos. Moisés Damián Perales-Escudero, Mizael Garduño Buenfil and Vilma Portillo Campos carried out the drafting of the manuscript. The three authors reviewed and approved the final content.

References

Asfura, E., & Real, N. (2019). La lectura literaria al egreso de la formación inicial docente. Un retrato de las prácticas lectoras declaradas por estudiantes de pedagogía en educación secundaria en lenguaje y comunicación. Calidad en la Educación, 50, 83-113. https://doi.org/10.31619/caledu.n50.719

Barzilai, S., & Weinstock, M. (2020). Beyond trustworthiness: Comprehending multiple source perspectives. In A. List, P. Van Meter, D. Lombardi & P. Kendeou (Eds.), Handbook of learning from multiple representations and perspectives (pp. 123-140). Routledge.

Borg. S., & Santiago-Sánchez, H. (2020). Cognition and good language teachers. In C. Griffiths & Z. Tajeddin (Eds.), Lessons from good language teachers (pp. 16-27). Cambridge University Press.

Brante, E. W. & Strømsø, H. (2018). Sourcing in text comprehension: A review of interventions targeting sourcing skills. Educational Psychology Review, 30(3), 773-799. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-017-9421-7

Bråten, I., Stadtler, M., & Salmerón, L. (2018). The role of sourcing in discourse comprehension. In M. F. Schober, D. N. Rapp & A. Britt (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of discourse processes (2nd ed., pp. 141-166). Routledge.

Cassany, D. (2003). Aproximaciones a la lectura crítica: teoría, ejemplos y reflexiones. Tarbiya, 32, 113-132.

Elche-Larrañaga, M., & Yubero-Jiménez, S. (2019). La compleja relación de los docentes con la lectura: el comportamiento lector del profesorado de educación infantil y primaria en formación. Bordón. Revista de Pedagogía, 71(1), 31-45.

Errázuriz, M. C., Becerra, R., Aguilar, P., Cocio, A., Davison, O., & Fuentes, L. (2019). Perfiles lectores de profesores de escuelas públicas de la Araucanía, Chile. Una construcción de sus concepciones sobre la lectura. Perfiles Educativos, 41(164), 28-46. https://doi.org/10.22201/iisue.24486167e.2019.164.58856

Errázuriz, M. C., Fuentes, L., Davison, O., Cocio, A., Becerra, R., & Aguilar, P. (2020). Concepciones sobre la lectura del profesorado de escuelas públicas de la Araucanía: ¿Cómo son sus perfiles lectores? Signos, 53(103), 419-448. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-09342020000200419

Ghaith, G. (2021). A study of the implicit reading beliefs of a cohort of college EFL readers and their responses to narrative text. Reading Psychology, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2021.1913461

Haas, C., & Flower L. (1988). Rhetorical reading strategies and the construction of meaning. College Composition and Communication, 39(2), 167-183.

Hernández, G. (2008). Teorías implícitas de lectura y conocimiento metatextual en estudiantes de secundaria, bachillerato y educación superior. Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa, 13(38), 737-771.

Hintz, C., & Tribunella, E. L. (2019). Reading children’s literature (2nd ed.). Broadview Press.

Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277-1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Jiménez Llanos, A. B. (2009). Un contraste de ideas entre niveles educativos. Las teorías implícitas de los profesores de educación infantil y primaria, secundaria y superior. In J. Marrero Acosta (Ed.), El pensamiento reencontrado (pp. 47-94). Octaedro.

Larrañaga, M., & Yubero, S. (2019). La compleja relación de los docentes con la lectura: el comportamiento lector del profesorado de educación infantil y primaria en formación. Bordón. Revista de Pedagogía, 71(1), 31-45. https://doi.org/10.13042/Bordon.2019.66083

Londra, F., Politti, M., & Saux, G. (2021). ¿Confías en esta fuente?: percepción de credibilidad de fuentes documentales y no-documentales en estudiantes universitarios. Revista Psicología UNEMI, 4(7), 40-52.

Lordán, E., Solé, I., & Beltran, F. (2015). Development and Initial Validation of a Questionnaire to Assess the Reading Beliefs of Undergraduate Students: The Cuestionario de creencias sobre la lectura. Journal of Research in Reading, 40(1), 37-56. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9817.12051

Makuc, M. (2008). Teorías implícitas de los profesores acerca de la comprensión de textos. Signos, 41(68), 403-422. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-09342008000300003

Makuc, M. (2020). Teorías implícitas de los estudiantes sobre comprensión de textos: Avances y principales desafíos de investigación en la formación inicial de profesores y otras disciplinas. Sophia Austral, (25), 71-92.

Makuc, M., & Larrañaga, E. (2015). Teorías implícitas acerca de la comprensión de textos: Estudio exploratorio en estudiantes universitarios de primer año. Signos, 48(87), 29-53. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-09342015000100002

Marrero Acosta, J. (2009). Escenarios, saberes y teorías implícitas del profesorado. In J. Marrero Acosta (Ed.), El pensamiento reencontrado (pp. 8-44). Octaedro.

Medrano, V., & Ramos, E. (2019). La formación inicial de los docentes de educación básica en México: Educación normal, Universidad Pedagógica Nacional, Otras instituciones de educación superior. INEE. https://www.inee.edu.mx/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/P3B111.pdf

Mo, X. (2020). Teaching reading and teacher beliefs. A sociocultural perspective. Springer.

Moore, P., & Narciso, E. (2011). Modelos epistémicos de la lectura en estudiantes mexicanos. Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa, 16(51), 1197-1225.

Munita, F. (2013). Creencias y saberes de futuros maestros (lectores y no lectores) en torno a la educación literaria. Ocnos, 9, 69-87. https://doi.org/10.18239/ocnos_2013.09.04

Parodi, G., Moreno-de-León, T., & Julio, C. (2020). Comprensión de textos escritos: reconceptualizaciones en torno a las demandas del siglo XXI. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 25(3), 775-795. https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.ikala.v25n03a10

Perales-Escudero, M., Busseniers, P., & Reyes Cruz, M. (2017). Variation in pre-service EFL teachers’ implicit theories of reading: A qualitative study. MEXTESOL Journal 41(4), 1-18. https://mextesol.net/journal/index.php?page=journal&id_article=2618.

Perales-Escudero, M., Vega, N., & Correa, S. (2021). Validation of the scale of implicit theories of reading comprehension (ETICOLEC as per its Spanish acronym) of in-service teachers. OCNOS. Revista de Estudios sobre la Lectura, 20(22), 21-32. https://doi.org/10.18239/ocnos_2021.20.2.2515

Perales-Escudero, M. D., Hernández González, D. G., & Sandoval Cruz, R. I. (2022). Condición socioeconómica, género, frecuencia lectora y teorías implícitas lectoras de profesores de lenguas en formación. Revista de Lengua y Cultura, 4(7), 26-36. https://repository.uaeh.edu.mx/revistas/index.php/lc/issue/archive.

Pozo, J., Scheuer, N., Mateos, M., & Pérez, M. (2006). Las teorías implícitas sobre el aprendizaje y la enseñanza. In J. I. Pozo, N. Scheuer, M. Pérez, & E. Martín (Eds.), Nuevas formas de pensar la enseñanza y el aprendizaje. Las concepciones de profesores y alumnos (pp. 95-134). Graó.

Prat, R., & Doval, E. (2005). Construcción y análisis de escalas. In J. P. Levi, & J. Varela (Eds.), Análisis multivariable para las ciencias sociales (pp. 44-88). Pearson.

Rodrigo, M. J. (1993). Representaciones y procesos en las teorías implícitas. In M. J, Rodrigo, A. Rodríguez, & J. Marrero (Eds.), Las teorías implícitas. Una aproximación al conocimiento cotidiano (pp. 95-117). Visor.

Rodrigo, M. J. (1997). Del escenario sociocultural al constructivismo episódico: Un viaje al conocimiento escolar de la mano de las teorías implícitas. In M. J. Rodrigo, & J. Arnay (Comps.), La construcción del conocimiento escolar (pp. 177-191). Paidós.

Rodrigo, M. J., & Correa, N. (2001). Representación y procesos cognitivos: Esquemas y modelos mentales. In C. Coll., J. Palacios. & A. Marchesi (Comp.), Desarrollo psicológico y educación, 2. Psicología de la educación escolar (pp. 117-135). Alianza.

Rodríguez Zidán, E. (2001). Teoría implícita y formación inicial del profesorado de Educación Media. Revista Enfoques Educacionales, 3(2), 145-155. https://doi.org/10.5354/0717-3229.2000.48741

Rodríguez, A., & González, R. (1995). Cinco hipótesis sobre las teorías implícitas. Revista de Psicología General y Aplicada, 48(3), 221-229.

Schraw, G. (2000). Reader beliefs and meaning construction in narrative text. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(1), 96-106. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.92.1.96.

Schraw, G., & Bruning, R. (1996). Readers’ implicit models of reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 31(3), 290-305. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.31.3.4

Schraw, G., & Bruning, R. (1999). How implicit models of reading affect motivation to read and reading engagement. Scientific Studies of Reading, 3(3), 281-302.

Shrestha, N. (2021). Factor analysis as a tool for survey analysis. American Journal of Applied Mathematics and Statistics, 9(1), 4-11. https://doi.org/10.12691/ajams-9-1-2

Tosi, C. (2017). La comprensión de textos especializados. Un estudio polifónico-argumentativo sobre las dificultades de lectura en los estudios de formación docente en la Argentina. Revista Actualidades Investigativas en Educación, 17(3), 1-22.

Vansteelandt, I., Mol, S., Caelen, D., Landuyt, I., & Mommaerts, M. (2017). Attitude profiles explain differences in pre-service teachers’ reading behavior and competence beliefs. Learning and Individual Differences, (54), 109-115.

Wynd,

C. A., Schmidt, B., & Schaefer, M. A. (2003). Two quantitative

approaches for estimating content validity. Western

Journal of Nursing Research,

25(5),

508–518. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945903252998

Appendix 1: The adapted ETICOLE Scale in Spanish

Indica tu grado de acuerdo o desacuerdo con la manera en que los siguientes enunciados completan la oración: “Creo que una comprensión lectora eficaz involucra…”.

1= Completamente en desacuerdo 2= En desacuerdo 3= Ni de acuerdo ni en desacuerdo |

4= De acuerdo 5= Completamente de acuerdo |

|||||

1. Cuestionar la veracidad de los mensajes del texto. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

2. Meterme en la trama del texto. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

3. Cuestionar las ideologías presentes en el texto. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

4. Emocionarme con los sucesos del texto. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

5. Replantear los mensajes del texto de acuerdo con mi propia apreciación. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

6. Descubrir los propósitos del autor |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

7. Entender libremente el mensaje del texto. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

8. Identificar información pertinente sobre el autor. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

9. Entender exactamente el mensaje del texto. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

10. Relacionar el texto con mis conocimientos previos. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

11. A partir del mensaje exacto del texto, hacerse una idea propia. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

12. Descubrir los mensajes implícitos del texto. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

13. Identificar el contexto histórico y cultural (por ejemplo, cuándo se escribió, las circunstancias del momento, dónde se publicó) del texto. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

14. Juzgar la pertinencia de los mensajes del texto para mi contexto. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

15. Aplicar el mensaje del texto a mi propia vida. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

16. Ajustar mi forma de leer al tipo de texto que estoy leyendo. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

17. Contrastar el mensaje del texto con los de otros textos relacionados. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

18. Analizar el crecimiento personal de los personajes. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

19. Descubrir el tipo de lectores a quienes se dirige el autor. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

20. Relacionar el texto con mi propia vida. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

21. Identificar varios puntos de vista en el texto. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

22. Comprender las ideas principales del texto. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

23. Hacerme una idea fiel al mensaje del texto. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

24. Comprender el texto de acuerdo con mis propias intenciones. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

25. Imaginarme intensamente lo que pasa en el texto |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

Appendix 2: The adapted ETICOLE Scale in English

Indicate your degree of agreement or disagreement with the way in which the statements below complete the sentence “I believe effective reading comprehension involves…”

1= Strongly Disagree 2= Disagree 3= Neither Agree nor Disagree |

4= Agree 5= Strongly Agree |

|||||

1. Questioning the veracity /authenticity of text messages |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

2. Immersing myself in the text´s plot. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

3. Questioning the ideologies present in the text. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

4. Getting excited about the events of the text. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

5. Rephrasing the messages in the text according to my own thinking. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

6. Finding out the author's purposes |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

7. Understanding the message of the text freely. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

8. Identifying relevant information about the author. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

9. Understanding the exact message of the text. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

10. Relating the text to my previous knowledge. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

11. Producing my own ideas from the text’s exact message. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

12. Discovering the implicit messages of the text. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

13. Identifying the historical and cultural context (e.g., when it was written, the circumstances of the time, where it was published) of the text. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

14. Assessing the relevance of the text's messages to my context. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

15. Applying the message of the text to my own life. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

16. Adjusting my way of reading to the type of text I am reading. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

17. Contrasting the message of the text with those of other related texts. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

18. Analyzing the personal growth of the characters. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

19. Discovering the type of readers to whom the author is addressing. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

20. Relating the text to my own life. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

21. Identifying various points of view in the text. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

22. Understanding the main ideas of the text. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

23. Understanding the text’s message accurately. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

24. Understanding the text according to my own intentions. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

25. Intensely imagining what is happening in the text. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|