Exploring Reticence to Write in L2: Notes for Teachers’ Professional Development

Explorando la reticencia a escribir en una L2: notas para el desarrollo profesional docente

Explorando a relutância em escrever em L2: notas para o desenvolvimento profissional de professores

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.18861/cied.2025.16.especial.4119

Gabriel

Díaz Maggioli

Universidad ORT

Uruguay

Uruguay

diaz_g@ort.edu.uy

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6686-2549

Received:

03/19/25

Approved: 06/02/25

How

to cite:

Díaz Maggioli, G. (2025). Exploring

Reticence to Write in L2: Notes for Teachers’

Professional Development. Cuadernos

de Investigación Educativa,

16(especial).

https://doi.org/10.18861/cied.2025.16.especial.4119

Developing writing proficiency is essential to communicative competence in foreign language learning, yet Uruguayan public secondary students frequently display reluctance toward writing in English, as noted by their teachers. This study investigates EFL teachers’ perceptions regarding student engagement in writing, aiming to determine the prevalence and underlying causes of the identified reticence, as well as the instructional practices teachers employ to address it. Utilizing a descriptive, survey-based approach, the study collected 58 responses—about 5% of Uruguay’s public EFL teaching population—via an electronic questionnaire. The instrument comprised both multiple-choice and open-ended questions to enable quantitative and qualitative analysis. Results reveal that 52.8% of teachers view students as generally reticent to write in English, while 47.2% observe partial reluctance. Contributing factors include students’ low confidence, restricted vocabulary, inadequate early exposure to writing, and lack of engagement with tasks perceived as irrelevant to their interests. While 94% of teachers dedicate class time to writing, many highlight time constraints and curricular requirements as significant barriers to adopting a more systematic approach. The process approach to writing (47%) is the most widely implemented methodology, followed by the product approach (11.7%), with just 5.8% using a genre-based approach. Notably, 11.7% of teachers report unfamiliarity with any writing pedagogy. The findings underscore the need for greater emphasis on process- and genre-based writing instruction in EFL classrooms. Future research should examine the effectiveness of specific pedagogical interventions, explore student perspectives on writing reluctance, and consider the role of teacher training in improving writing outcomes in EFL contexts.

Keywords: EFL writing instruction, student writing reluctance, teacher perceptions, curriculum, foreign language education.

La competencia escrita es esencial para lograr una comunicación eficaz en lenguas extranjeras, pero muchos estudiantes de secundaria pública en Uruguay muestran reticencia a escribir en inglés, según la percepción de sus docentes. Este estudio investiga cómo los profesores de inglés como lengua extranjera valoran el compromiso de sus alumnos con la escritura, indagando tanto la frecuencia como las causas de dicha reticencia, así como las estrategias pedagógicas utilizadas para superarla. Mediante una encuesta descriptiva respondida por 58 docentes —cerca del 5 % del total nacional— se recabaron datos cuantitativos y cualitativos a través de preguntas cerradas y abiertas. El 52,8 % de los docentes considera que sus estudiantes son poco propensos a escribir en inglés, mientras que un 47,2 % detecta una reticencia parcial. Factores asociados a esta dificultad incluyen la baja confianza en capacidades propias, escaso vocabulario, limitada exposición temprana a la escritura y desinterés por tareas poco relacionadas con sus intereses. Si bien el 94 % de los docentes destina tiempo a la escritura en sus clases, muchos mencionan la falta de tiempo y las demandas curriculares como trabas para una enseñanza más estructurada. El enfoque por procesos es el más frecuente (47 %), seguido por el enfoque por producto (11,7 %), mientras que solo un 5,8 % utiliza el enfoque basado en géneros. Un 11,7 % admite desconocer enfoques didácticos específicos. Los resultados resaltan la necesidad de promover prácticas sistemáticas centradas en procesos y géneros. Se recomienda profundizar en la formación docente y explorar nuevas estrategias para fortalecer la producción escrita en inglés.

Palabras clave: enseñanza de la escritura en inglés como lengua extranjera, reticencia a la escritura, percepciones docentes, currículo, educación en lengua extranjera.

Desenvolver a proficiência na escrita é fundamental para a competência comunicativa em línguas estrangeiras, mas muitos estudantes do ensino médio público uruguaio costumam mostrar relutância em escrever em inglês (L2), segundo relatam seus professores. Este estudo analisou as percepções de professores de inglês sobre o engajamento de seus alunos na comunicação escrita, buscando identificar a frequência e as causas da relutância, bem como as estratégias pedagógicas utilizadas para enfrentá-la. Utilizou-se um questionário descritivo enviado a professores de inglês da rede pública; foram recebidas 58 respostas, representando cerca de 5% do total de docentes de ILE (inglês como língua estrangeira) do Uruguai. O instrumento incluiu questões fechadas e abertas, permitindo análises quantitativas e qualitativas. Os resultados mostram que 52,8% dos professores percebem grande relutância dos alunos para escrever em inglês, enquanto 47,2% notam uma relutância parcial. Os fatores mais citados são: baixa autoconfiança, vocabulário limitado, pouca experiência prévia com a escrita e desinteresse por tarefas pouco conectadas à realidade dos alunos. Embora 94% dos docentes dediquem tempo à escrita na sala de aula, muitos relatam falta de tempo e exigências curriculares como barreiras para um ensino mais estruturado. O enfoque processual é o mais usado (47%), seguido pelo enfoque no produto (11,7%); só 5,8% utilizam a abordagem baseada em gêneros, e 11,7% admitem não conhecer metodologias didáticas específicas. Os dados indicam a necessidade de fortalecer práticas de ensino de escrita baseadas em processos e gêneros. Recomenda-se aprofundar na formação docente e explorar novas estratégias para fortalecer a produção escrita em inglês.

Palavras-chave: ensino da escrita em inglês como língua estrangeira, relutância em escrever, percepções dos professores, currículo, educação em língua estrangeira.

This article reports on a pilot study undertaken to assess the veracity of an often-heard perception by teachers regarding the learning of writing in public secondary schools in Uruguay.

English is the main foreign language taught at the secondary level, and students are expected to attain a B1 level at the end of six years of secondary studies. However, the attainment of this level is still under analysis. One of the frequently heard complaints by teachers is that students in public secondary schools are reticent to write. They cite as evidence the fact that most of the students in their various groups fail to complete the written tasks set either as homework or as part of the paper-based assessments.

However, these claims have so far been met with skepticism by national authorities and have not been systematically addressed by research. Developing proficiency in a foreign language includes the mastery of three main modes of communication: interpretive (listening and reading), interpersonal (interactive speaking and listening), and presentational (writing and monologic speaking); hence, the relevance of this pilot study (Díaz Maggioli, 2024).

In light of this situation, the present study sought to understand the perceptions of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teachers in public secondary schools, so as to confirm these widely held opinions or discard them. Once this understanding is obtained, it is hoped that the present pilot study may form the basis of a more extensive and longitudinal research project involving supervisors, teachers, and students alike.

The purpose of the study is to understand whether EFL teachers in public secondary schools in Uruguay consider their students choose not to engage with the development of the written presentational mode. Hence, the pilot project sought to answer the following questions:

1. Do EFL teachers in secondary schools in Uruguay perceive that their learners are reticent to write?

2. If so, why do they think that this is the case?

3. If not, what do they perceive as good practice in teaching writing?

4. What approaches to the teaching of the written presentational mode do teachers report implementing?

This project can be sustained in a number of reasons why the mastery of the written presentational mode is relevant in education, in general, and in EFL teaching and learning in particular. In the next section, there is a discussion of these reasons using evidence from previous research on the relevance of the research questions.

Research in L2 writing was intensively pursued in the last three decades of the twentieth century. Since then, a number of studies have shed light on the complexity of this mode of communication. The following section explores some theoretical developments, mostly in the first two and a half decades of the twenty-first century, without losing sight of the foundational ideas that have propelled research on writing to its current status.

Developing writing skills is crucial in foreign language education. Proficiency in writing enables learners to effectively convey ideas, emotions, and information, thereby enhancing their overall communicative competence. This skill does not only facilitate academic success but also prepares students for real-world interactions where written communication is essential.

Research has underscored the significance of writing in language learning. For instance, studies like that of Bayat (2014) found that employing process-based approaches, such as drafting and peer reviews, helped learners develop a sense of ownership and improved their writing efficacy. Similarly, a study highlighted in the International Journal of Language Education emphasizes that writing proficiency is vital for academic success, as it requires learners to employ their linguistic competence to generate ideas, select appropriate diction, and construct coherent texts (Suastra & Menggo, 2020).

Moreover, writing serves as a tool for learning, allowing students to organize and refine their thoughts. As noted in other studies (Jiang & Kalyuga, 2022), writing-to-learn activities help students internalize new information and enhance their understanding of the language. Additionally, integrating writing tasks with other language skills promotes a more holistic learning experience, reinforcing vocabulary and grammatical structures.

Incorporating writing into formal education also fosters critical thinking and creativity. Through writing, students engage in reflective practices, analyze diverse perspectives, and articulate viewpoints. This process not only bolsters their language abilities but also contributes to their intellectual growth.

Last, but not at all the least, research has shown that L2 writing instruction positively affected L1 writing performance, suggesting that developing writing skills in a foreign language can enhance writing abilities in one's native language (Mehrabi, 2014).

Challenges

to the Teaching of Writing in Public Education

As we have seen, writing is a critical skill in second language (L2) acquisition, playing a fundamental role in both academic development and communicative competence. Despite its importance, students in Uruguayan public secondary schools often seem to exhibit reticence toward writing tasks, whether as part of coursework or formal assessments.

This reluctance is not unique to Uruguay but has been documented in various educational contexts worldwide, particularly in public education systems where systemic constraints and limited instructional innovation hinder the development of the written presentational mode. Understanding this reluctance requires examining both cognitive and pedagogical dimensions of L2 writing, including the role of structured writing instruction, pre-task planning, writing as a social practice, and the interplay between L1 and L2 literacy. It is to a consideration of these different dimensions of the teaching of the written presentational mode that we now turn.

Writing

as a Social and Cognitive Process

Traditionally, writing in L2 classrooms has been treated as an isolated skill, often relegated to grammar-focused drills or assessed through decontextualized written exercises. However, research highlights the importance of engaging students in meaningful, contextually relevant writing practices to foster motivation and skill development. Hayik (2023) demonstrates how integrating social justice themes into writing instruction—to document and write about real-life issues—can increase student engagement and improve written production. In a study with Palestinian-Israeli EFL learners, she found that students who were given the opportunity to write about social issues relevant to their lives produced more sophisticated and personally invested writing. This finding may indicate that Uruguayan students' reluctance toward writing could be alleviated by incorporating more personally meaningful and socially relevant writing tasks into the curriculum (Hayik, 2023).

Early

Writing Exposure and the Role of Pedagogical Approaches

Whereas most students entering secondary public schools in Uruguay have had, at least, three years of EFL classes at the primary level, secondary educators insist that they arrive at that level without the necessary linguistic resources to engage in developing their language proficiency, particularly in what pertains to the development of writing.

A key challenge in secondary education is that many students do not receive adequate preparation for writing in their formative years, leading to frustration and avoidance of writing tasks in later stages of their education. Research by Moon (2008) highlighted that writing is often overlooked in primary L2 classrooms, leading to a disconnect between early language learning and later writing demands in secondary education. The study emphasized that writing should not be introduced solely as a means of language reinforcement or assessment but should be integrated with other language skills, such as reading and speaking, to foster holistic language development. This aligns with the perceived situation in Uruguay, where writing is often treated as a formal requirement rather than a communicative ability, potentially resulting in students’ lack of confidence and reluctance to engage in writing tasks in secondary education.

Furthermore, Moon (2008) underscored the bidirectional relationship between L1 and L2 writing skills, supporting Cummins’ (1981) Common Proficiency Model, which argues that skills acquired in one language can positively transfer to another. This suggests that Uruguayan students might benefit from explicit instructional strategies that build on their L1 literacy to develop L2 writing proficiency, rather than viewing them as separate domains.

The

Teaching of Writing in Secondary Schools in Uruguay

The Uruguayan curriculum aligns writing instruction in English with the National Curriculum Framework (MCN) (ANEP, n.d., a), emphasizing a competency-based approach. Writing is considered one of the four fundamental language skills, and students are expected to produce coherent, structured, and contextually relevant texts. At the foundational levels (A1), students write simple descriptions about themselves, their families, and daily routines, while at more advanced levels, they are encouraged to express opinions, write argumentative texts, and engage in reflective writing. The curriculum promotes writing as a process, including drafting, revising, and receiving feedback, rather than just producing a final product.

Methodologically, the curriculum supports active learning strategies, such as project-based learning, collaborative writing, and the use of digital tools. Portfolios are recommended to track students’ progress, and peer and self-assessment are encouraged to help students take ownership of their learning. Teachers are advised to integrate metalinguistic reflection, helping students understand language structures to improve accuracy and coherence. Additionally, writing tasks include various text types, such as reports, letters, blog entries, and job application materials, ensuring students develop diverse communicative skills (ANEP, n.d., b).

Despite these structured guidelines, teachers continue to report that students in Uruguayan public schools face significant challenges in developing writing proficiency in English. Limited exposure to the language, restricted classroom time, and a tendency to focus on memorized structures rather than fostering critical and creative expression seem to hinder their progress. Moreover, writing is often described in the curriculum documents (ANEP, n.d., a) as a final task rather than a recursive process, reducing opportunities for feedback and improvement. These issues highlight a potential gap between curricular expectations and actual classroom practices.

To address these challenges, the curriculum recommends strengthening process-based writing instruction, encouraging students to engage in continuous drafting and revision, and leveraging technology to enhance interaction and feedback.

Traditions

and Approaches to the Teaching of Writing

The development of writing proficiency is a complex and multifaceted process that requires structured instructional support. Díaz Maggioli (2024) underscores the necessity of scaffolding students’ writing development to facilitate the production of coherent, purposeful, and structured texts. He explores three predominant approaches to writing instruction: the product approach, the process approach, and the genre-based approach.

The product approach, rooted in structuralist traditions, emphasizes linguistic accuracy and correctness, guiding students to analyze and imitate model texts to internalize grammatical structures and stylistic conventions. While this method fosters textual accuracy, it has been criticized for limiting creativity and communicative effectiveness (Hyland, 2003).

The process approach, by contrast, conceptualizes writing as a recursive activity involving brainstorming, drafting, peer feedback, revising, and editing (British Council, n.d.). This approach encourages students to develop their ideas over multiple iterations, promoting critical thinking and personal voice in writing (Zamel, 1987). However, its relative lack of emphasis on genre conventions may pose challenges for students attempting to write within specific academic or professional discourse communities.

Díaz Maggioli (2024) advocates for the adoption of a genre-based approach as a comprehensive framework that integrates the strengths of both product- and process-oriented instruction while addressing their respective limitations. Drawing on Systemic Functional Linguistics (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2004), this approach emphasizes the social and communicative functions of writing by guiding students through the analysis and production of different genres. The instructional process typically involves introducing a model text, deconstructing textual features, engaging students in guided writing activities, facilitating independent production, and finally, comparing texts within the same genre as well as across genres. Through this structured progression, students gain an understanding of how language operates within specific contexts, enabling them to navigate diverse communicative situations effectively (Martin, 2009). Furthermore, Díaz Maggioli (2024) highlights the importance of task-based writing activities that reflect authentic communicative needs, thereby ensuring that students not only develop linguistic competence but also acquire the discursive strategies necessary for effective communication in real-world contexts.

A key component of this approach is assessment, which must extend beyond grammatical accuracy to evaluate both process and product. Díaz Maggioli (2024) proposes rubrics that assess coherence, genre adherence, language control, and communicative intent, reinforcing the idea that writing instruction should prioritize meaning-making alongside linguistic correctness. Additionally, peer review and feedback mechanisms are essential in fostering students’ metacognitive awareness of their writing practices and providing opportunities for iterative refinement. The integration of digital tools further enhances this process, enabling multimodal composition, collaborative editing, and real-time feedback, thereby aligning writing instruction with contemporary literacy practices.

Despite its advantages, the genre-based approach presents challenges in implementation, including the time-intensive nature of genre analysis, the need for explicit instruction, and the potential for rigid adherence to textual conventions (Díaz Maggioli, 2024).

However, with careful scaffolding and strategic pedagogical interventions, these obstacles can be mitigated. By adopting a balanced instructional approach that combines structured support with opportunities for independent exploration, educators can facilitate the development of students’ writing competence in ways that are both academically rigorous and socially relevant. In this regard, Author’s work aligns with broader calls for a sociocultural perspective on writing pedagogy, which emphasizes the role of language as a dynamic, socially embedded system that evolves in response to communicative needs (Brisk, 2006; Gibbons, 2009). This perspective is particularly relevant for foreign language education, where learners must not only acquire linguistic proficiency but also develop the ability to participate meaningfully in varied discourse communities.

The sociocultural perspective and the scaffolded nature of learning the written presentation mode have also been the focus of other recent research projects, described below.

The

Role of Imitation and Scaffolded Writing Instruction

Students' hesitation to engage in writing can also stem from a lack of familiarity with the conventions of written discourse in L2. Research on imitative learning in writing instruction suggests that providing students with structured models can enhance writing self-efficacy and fluency, thus reinforcing the argument for a genre-based approach. Chen (2023) found that exposing students to well-crafted model texts (presenting, modeling, and deconstructing a model text) and guiding them through structured imitation exercises (collaborative and independent construction of the text) significantly improved their ability to produce coherent and purposeful writing. This approach, when combined with peer support and reflective writing activities, fosters a sense of control over the writing process, making students more willing to engage in extended writing tasks. Given that many Uruguayan public-school students may not have extensive exposure to varied writing genres in English, incorporating these learning strategies could help bridge the gap and reduce writing reticence.

The

Role of Pre-Task Planning and Process-Based Approaches

One of the key factors that has been found to influence students' reluctance to write is the cognitive load associated with producing extended texts in a foreign language. Ellis (2022) explores the effects of pre-task planning (PTP) on writing performance, showing that while PTP generally improves fluency and coherence, its impact on grammatical accuracy is less consistent. His study suggests that allowing students time to plan their ideas and structure their writing before engaging in the actual writing task can significantly improve their output. This could be particularly relevant in Uruguayan classrooms, where time constraints and syllabus pressures often limit students’ ability to engage in process-based writing approaches that emphasize drafting, feedback, and revision.

Other

Integrative Perspectives

Finally, we should highlight other pedagogical trends in the teaching of writing that advocate for integrative approaches combining elements from all three methodologies described above to address their respective limitations.

For instance, Badger and White (2000) proposed a "process genre approach," which merges the recursive practices of the process approach with the contextual sensitivity of genre-based instruction. This hybrid model allows students to engage in the iterative development of their writing while being mindful of genre-specific conventions and audience expectations.

Similarly, Raftari and Abbasvand (2023) analyzed the strengths and weaknesses of product, process, and genre approaches, suggesting that an understanding of these methodologies is pivotal for effective writing instruction.

Finally, Jiang and Kalyuga (2022) examined the cognitive challenges associated with foreign language writing and how collaborative learning can mitigate these difficulties. Their study compared two instructional conditions—individual and collaborative—within a process-genre approach, which integrates recursive writing strategies with explicit genre instruction. The findings revealed that students in the collaborative writing condition produced higher-quality texts with improved coherence, lexical richness, and grammatical accuracy, while also experiencing lower cognitive load. This outcome supports the collective working memory theory, which posits that distributing cognitive effort among peers enhances learning efficiency and reduces mental strain. Given that writing reluctance in Uruguayan public schools often stems from students' struggles with cognitive overload and lack of confidence, implementing collaborative writing strategies could significantly enhance student engagement and performance.

A key finding of that study was that the collaborative approach not only improved writing outcomes but also increased instructional efficiency, as students in group settings required less cognitive effort to achieve better results.

The findings from these studies provide key insights into why students in Uruguayan public schools may be hesitant to engage with writing and how their engagement could be enhanced through more effective pedagogical approaches. Several key strategies have emerged from this discussion of the literature:

1. Integrating Socially Relevant Writing Tasks: As demonstrated by Hayik (2023), connecting writing activities to students' lived experiences can increase motivation and engagement.

2. Early Writing Instruction and Integration with Other Skills: Research by Moon (2008) suggests that delaying writing instruction can create long-term resistance; thus, integrating writing from early stages is crucial.

3. Using Imitative and Scaffolded Writing Approaches: Chen (2023) highlights the benefits of exposing students to structured models to improve writing confidence and competence.

4. Incorporating Pre-Task Planning to Reduce Writing Anxiety: Ellis (2022) demonstrates that allowing students time to plan their writing before engaging in it can improve fluency and coherence.

However, before advancing any solution, it is essential to confirm whether teachers’ perceptions about students’ reticence to write must happen. To this avail, in the following section, the methodology of the pilot study is discussed.

Design

This study adopted a descriptive, survey-based research design to explore EFL teachers' perceptions of students' engagement with the written presentational communication mode in Uruguayan public secondary schools. The primary objective was to determine whether teachers perceive their students as reticent to engage in writing tasks and to identify the factors contributing to this reluctance. Additionally, the study sought to document the instructional approaches that teachers implement to develop students' writing skills.

A questionnaire was selected as the primary data collection tool due to its efficacy in capturing subjective perspectives from a random sample of participants in a standardized manner (Dörnyei & Taguchi, 2010). Given that the study focused on teachers' perceptions rather than direct student performance, the questionnaire allowed respondents to provide both objective and qualitative data, enabling the study to identify patterns and trends in teaching practices and beliefs.

Participants

and Sampling

The questionnaire was distributed electronically to EFL teachers working in Uruguay’s public secondary schools via social media platforms (Facebook, LinkedIn, and Instagram). A total of 58 responses were collected. While there are no precise records of the total number of EFL teachers in Uruguay, the estimated number of responses constitutes approximately 5% of the EFL teaching population in the country. This sample size, albeit limited, is deemed sufficient for a pilot study, as it allows for the identification of preliminary trends and key themes regarding writing instruction and student engagement (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). Furthermore, in exploratory research, samples between 5% and 10% of a population can provide meaningful insights, particularly when the population is homogeneous in terms of professional background and teaching context (Mackey & Gass, 2016). The data collected from this sample provided a solid foundation for refining research instruments and hypotheses for future large-scale studies.

Data

Gathering

The questionnaire consisted of seven questions, combining multiple-choice and open-ended items to ensure a comprehensive understanding of teachers' perceptions and practices:

1. Three multiple-choice questions:

- What grades do teachers currently teach?

- Do teachers perceive their students as reticent to engage in writing?

- Do teachers devote specific class time to explicitly teaching the written presentational communication mode?

2. Four open-ended questions:

- If teachers perceive students as reticent, what do they believe are the reasons for this?

- What approaches to the teaching of writing do teachers report implementing?

- Why do teachers think students are reticent (or not reticent) to write?

- What suggestions do they have for improving the current state of writing instruction?

This mixed-format approach ensured that the study collected both objective data to identify trends, and qualitative data to explore the depth and diversity of teacher perspectives. The open-ended questions allowed for richer, more nuanced insights, facilitating the identification of recurring themes and potential areas for pedagogical intervention (Bryman, 2012).

Ethical

Considerations

To uphold ethical research standards, the questionnaire was administered using an electronic survey tool that ensured the anonymity of respondents. Participants were required to complete a consent form before accessing the questionnaire, explicitly indicating their willingness to participate. If a respondent did not consent, they were not redirected to the questionnaire, ensuring voluntary participation in accordance with ethical research principles (BERA, 2018).

Furthermore, all data were securely stored to protect participant confidentiality. Responses were kept in a password-protected online folder in the researcher's cloud storage and additionally backed up on an external data unit; also password-protected. These measures ensured compliance with ethical guidelines for data management and participant privacy.

Data

Analysis

The questionnaire was open for responses over a two-week period, allowing teachers adequate time to participate. Once data collection was completed, responses were aggregated and analyzed through two cycles of coding, which led to the establishment of themes that were subjected to thematic analysis. The latter involved identifying patterns in teachers' explanations regarding students' reluctance to write and their instructional approaches.

This methodological approach provided a structured yet flexible framework for capturing the complexity of teachers' perceptions of EFL writing instruction in secondary schools in Uruguay, forming the basis for further research into effective pedagogical strategies to enhance students’ engagement with writing.

Results

The responses to the questionnaire yielded many interesting insights into the reality of the teaching of writing in Uruguayan secondary schools. The following themes emerged from the data gathered:

Prevalence

of Reticence to Writing in English

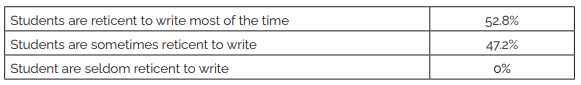

The survey data indicate that a significant percentage of students exhibit reluctance towards writing in English. A majority of respondents (52.8%) stated that their students are reticent to write in English, while 47.2% reported that their students are sometimes reluctant. It should be noted that there were no responses indicating students are not hesitant when engaging in writing tasks. Table 1 summarizes these responses.

Table

1

Percentage

of responses reporting reticence to writing

Writing

Instruction Practices

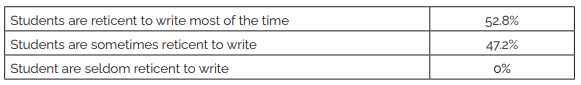

While recognizing the importance of writing instruction, a surprising 94% of teachers reported dedicating specific class time to teaching students how to write, whereas only 6% indicated that they do not explicitly teach writing skills. Table 2 summarizes those figures. Those who do incorporate writing instruction primarily focus on helping students generate ideas, organize their thoughts, and structure their writing according to different discourse types. However, time constraints were cited as a key barrier to incorporating more writing-focused lessons, with some teachers relying on textbook exercises rather than explicit instruction on writing as a process.

Table

2

Implementation

of writing instruction in classes

Approaches

to Writing Instruction

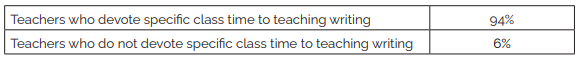

Teachers reported using a variety of approaches to teaching writing as evidenced in Table 3, but there is no consistent methodology across schools. The most common approach was the process approach (47%). Some teachers (11.7%) reported using the product approach. A much smaller percentage (5.8%) favored a genre-based approach. Notably, 20.5% of teachers stated that they do not follow a specific approach, instead adapting their teaching based on class dynamics and available instructional time. What is surprising is that 11.7% of the respondents reported not being familiar with any approach whereas 3.3% opted not to answer this questions.

Table

3

Instructional

approaches used by teachers to develop writing

Suggested

Improvements for Writing Instruction

Teachers provided a range of suggestions to enhance the teaching of writing in public schools. A common theme was the need to allocate more classroom time to writing instruction, ensuring that students receive explicit guidance on how to develop their ideas and structure their texts. While 94% reported allocating specific class time to the development of writing, the time available seems not to be enough.

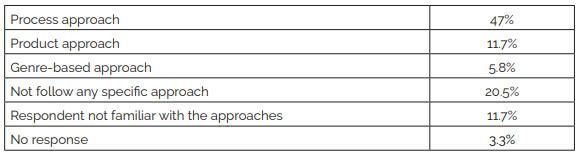

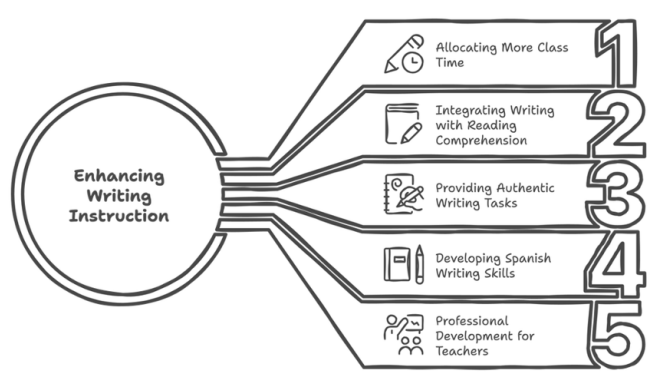

Several teachers emphasized the importance of integrating writing with reading comprehension activities, as well as providing students with authentic, meaningful writing tasks that connect to their interests and real-world experiences. Additionally, some respondents suggested that students should first develop stronger writing skills in Spanish before being expected to produce coherent texts in English. Finally, professional development for teachers was identified as a crucial factor in improving writing instruction, as many educators felt they lacked training in effective writing pedagogy. These opinions are summarized in Figure 1 below.

Figure

1

Participants’

recommendation to improve writing instruction

Note. This diagram was generated by napkin.ai based on the text that precedes it.

The analysis of the questionnaire responses confirms a widespread perception among Uruguayan secondary EFL teachers that their students are reticent to engage in writing tasks in English. However, beyond this general trend, the data suggest that such reluctance is not monolithic. Teachers’ open-ended responses provide insight into a range of interrelated cognitive, affective, institutional, and pedagogical factors that contribute to students’ disengagement, which align with—and in some cases challenge—assumptions derived from the literature on L2 writing instruction.

Misalignment

between Theory and Practice in Writing Instruction

A clear discrepancy emerges between the process-oriented and genre-based approaches endorsed in the literature and the instructional practices reported by teachers. Although 94% of respondents report allocating time to teaching writing, only 47% explicitly adopt a process approach, and a mere 5.8% mention using genre-based instruction. This is striking, given that the recommendations of the MCN explicitly advocate for a process-based approach. Additionally, as has been discussed in the theoretical background section of this paper, much of the literature emphasizes the pedagogical value of these approaches in scaffolding students’ development of textual coherence, audience awareness, and discursive fluency.

Teachers’ responses frequently reveal that writing is implemented as a one-shot activity rather than a recursive process. For instance, one teacher notes that “students don’t like to rewrite several times,” suggesting that the iterative nature of writing, central to the process approach (Zamel, 1987), may not be sufficiently modeled or supported. Similarly, references to “doing the writing task at the end” or relying solely on textbook prompts imply a product-oriented approach that may not adequately promote student agency, reflection, or ownership of their work.

The

Role of Instructional Scaffolding and Pre-Writing Support

The lack of consistent application of scaffolding strategies was a recurring theme in teachers’ responses. Several participants mentioned that students “lack ideas” or “don’t know where to start,” pointing to a failure to integrate structured pre-writing activities, such as brainstorming, guided modeling, or collaborative drafting. This finding supports Ellis’ (2022) claim that pre-task planning can ease the cognitive load associated with writing in an L2, making the task more accessible and less anxiety-inducing for learners.

Interestingly, the few respondents who reported employing a genre-based approach described a more supportive instructional sequence. One teacher explained: “I always start with pre-writing activities to give them a lot of input, we see lots of models, then we write one collaboratively, and just then they write on their own.” This mirrors the teaching-learning cycle advocated by Martin (2009) and Díaz Maggioli (2024), which gradually moves students from supported practice to independent production. Such accounts suggest that where scaffolding is present, students’ engagement and confidence may increase, a hypothesis supported by both the literature and teachers’ own observations.

Institutional

Constraints and Curriculum–Practice Discrepancies

Another prominent theme concerns the constraints imposed by institutional realities, including limited instructional time, lack of pedagogical training, and competing curricular demands. One teacher summarized this tension succinctly: “There is not enough time to help each student with their writing skills. The book doesn’t help either.” Despite curricular documents that advocate for active learning and the use of portfolios and revision cycles (ANEP, n.d. a), teachers often report reverting to grammar-focused or assessment-driven tasks due to practical limitations. As one participant reported, “I review or teach the main grammar they will need, I work reading and then they have to produce writing pieces, sometimes some sentences, to a paragraph to end in a short text.”

These constraints echo findings from Jiang and Kalyuga (2022), who identify time and cognitive overload as major barriers to effective writing instruction.

The fact that 11.7% of teachers reported being unfamiliar with any approach to writing pedagogy underscores a systemic gap in professional development. This aligns with the theoretical concern that without adequate teacher training, even the best curriculum remains unimplemented (Brisk, 2006; Díaz Maggioli, 2024). Professional development programs focused on the application of process- and genre-based approaches could therefore be a powerful lever for change.

Students’

Reticence: Affective and Sociocultural Dimensions

Teachers overwhelmingly report that students perceive writing as a tedious and purposeless activity, which discourages their participation. One teacher highlighted this issue by stating, "They have lost the habit of writing in general, and they believe that writing is a tedious process that takes lots of time, seeing it as boring for them." This suggests that writing is not being framed as an engaging, communicative skill but rather as a burdensome task.

Another teacher emphasized the lack of meaningful connections between writing assignments and students’ lived experiences, stating, "They are [reticent to write] because most of the time, there is no real purpose." This aligns with research advocating for authentic, socially relevant writing activities that motivate students by making tasks personally significant (Hayik, 2023). Similarly, another teacher observed, "In my opinion, it is because they find the writing tasks boring or not motivating." These responses highlight how decontextualized assignments fail to capture students' interest, reinforcing disengagement with writing.

Some teachers noted that when writing tasks do carry personal meaning, students show greater willingness to engage. One respondent shared, "I find them less reluctant when what they have to write is personally meaningful or has a purpose." This testimony suggests that incorporating personal narratives, real-world writing situations, or socially relevant topics could increase student engagement. Another teacher pointed out that the dominance of technology has changed how students interact with written communication, stating that they do not write "because they are used to technology." This may indicate that traditional pen-and-paper tasks fail to align with students’ digital literacy practices, suggesting that integrating multimodal composition or digital storytelling could enhance motivation.

Furthermore, several teachers highlighted students’ struggle with idea generation, which further alienates them from writing tasks. One teacher stated, "Most students do not like writing in their L1 and feel reluctant to do it in English. They lack ideas and creativity. They tend to look for easy and quick stimulations, and writing takes practice, patience, and time." This insight supports research indicating that students need structured scaffolding, brainstorming exercises, and model texts to develop the confidence to engage in extended writing (Díaz Maggioli, 2024; Yasuda, 2011).

In contrast, a few teachers who incorporated more socially meaningful tasks reported higher student engagement. This supports Hayik’s (2023) assertion that writing becomes more motivating when learners write about topics they care about. The data suggest that enhancing task authenticity and relevance could mitigate students’ disengagement and foster a more positive relationship with writing.

Cross-Linguistic

and Developmental Considerations

Several teachers commented on students’ lack of writing habits in their first language (Spanish), suggesting that foundational literacy skills may be underdeveloped. One respondent stated, “Students need to learn to write in Spanish first, before we expect them to do it in English.” This insight is consistent with Cummins’ (1981) Common Underlying Proficiency Model, which posits that skills acquired in one language can transfer to another. The implication is that L2 writing instruction cannot be isolated from broader questions of literacy development across the curriculum.

As a pilot study, this research provides useful preliminary insights into EFL teachers’ perceptions of students’ reluctance to engage in writing. However, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the study relies on voluntary responses, which may introduce self-selection bias, as those who chose to participate may have particularly strong views on writing instruction. Additionally, the total number of EFL teachers in Uruguay remains undetermined, making it difficult to ascertain the full representativeness of the 58 responses, which constitute approximately 5% of the estimated teaching population. While this percentage is adequate for an exploratory study (Mackey & Gass, 2016), future research should aim to increase participation to enhance the trustworthiness of findings so as to affect policy development.

Another limitation is the sole reliance on teachers' self-reported perceptions, which, while valuable, do not provide direct evidence of student writing performance. Teachers' responses reflect their observations and professional insights, but students' perspectives on writing reluctance were not explored. A more comprehensive approach could triangulate data by incorporating student surveys, classroom observations, and analysis of student writing samples to validate and expand upon teachers’ perceptions.

Finally, while the questionnaire format allowed for a balance of objective and qualitative data, the depth of responses was limited by the constraints of the instrument. Some open-ended responses lacked elaboration, suggesting that follow-up interviews or focus groups could provide richer, more detailed insights into the factors affecting students’ writing engagement.

Given the key themes that emerged from this pilot study, future research should focus on targeted interventions and deeper explorations of writing instruction in Uruguayan public schools. Several potential research directions emerged:

Investigating

Student Perspectives

Future studies should incorporate students' viewpoints to understand their attitudes, challenges, and motivations regarding writing. A comparative analysis between teachers’ perceptions and students’ self-reported experiences could provide a fuller picture of the issue.

Classroom-Based

Research on Writing Practices

Observational studies or action research projects could document how writing is actually being taught in classrooms. This would help identify effective instructional strategies and the extent to which these writing approaches are being implemented.

Intervention

Studies on Process and Genre-based Writing

Given that the study found limited use of drafting, feedback, and revision cycles, as well as of the genre-based approach, future research should examine the impact of explicit process-based writing instruction on student engagement and writing outcomes. Experimental or quasi-experimental designs could compare classrooms using process-writing methodologies versus those using traditional product-based approaches.

Professional

Development for EFL Teachers

The study revealed that many teachers feel unprepared to teach writing effectively, indicating a need for teacher training programs focused on writing pedagogy. Research on the impact of professional development workshops on teachers' confidence and instructional strategies would be highly beneficial.

Integration

of Digital Writing Tools

Given that some teachers noted that students engage more readily with digital forms of communication, future research should explore how technology-enhanced writing instruction (e.g., collaborative online writing, digital storytelling, or AI-assisted feedback) can foster engagement and writing development.

Early

Writing Exposure and Cross-Linguistic Transfer

Since teachers frequently cited students' lack of writing habits in their first language as a barrier to L2 writing, research should explore how early writing instruction in Spanish influences writing development in English. This aligns with Cummins’ (1981) Common Underlying Proficiency Model and could inform curriculum planning to create stronger foundational writing skills in both languages.

In short, this pilot study has confirmed the widespread perception that EFL students in Uruguayan public schools are reticent to engage in writing tasks. It has also highlighted key institutional and pedagogical barriers, including time constraints, insufficient scaffolding, lack of process-based or genre-based writing instruction, and a perceived disconnect between writing tasks and students' real-world experiences. Addressing these challenges requires systemic changes in curriculum design, teacher training and development, and instructional methodologies to ensure that writing is not just an assessment-driven skill, but a meaningful communicative practice that students develop progressively and with confidence.

By expanding on this research through broader sample sizes, more diverse methodologies, and experimental interventions, future studies can provide evidence-based recommendations for minimizing student reluctance to write in English and fostering a more engaging, effective, and inclusive writing curriculum in Uruguayan public secondary education.

Notes:

Final

approval of the article:

Lourdes

Cardozo-Gaibisso, PhD, guest editor of the special issue.

Authorship

contribution:

Gabriel

Díaz Maggioli declares

the article is a report of a pilot research project he undertook

recently. As such, he designed the project, selected the most

appropriate methodology, designed data gathered instruments, gathered

and analyzed the data and wrote the article entirely himself.

Availability

of data:

The dataset

supporting the findings of this study is not publicly available.

Administración Nacional de Educación Pública (ANEP). (n.d. a). Inglés - DGES: Programa de Educación Media Superior. Dirección General de Educación Secundaria. https://www.anep.edu.uy/sites/default/files/images/Archivos/programas-ems/finales/tab-1/Ingl%C3%A9s%20-%20DGES.v3.pdf

Administración Nacional de Educación Pública (ANEP). (n.d. b). Inglés - Tramo 5: Programa de Educación Básica Integrada. Dirección General de Educación Secundaria. https://www.anep.edu.uy/sites/default/files/images/te-programas/2023/finales/espacios/espacio-comunicacion/Ingl%C3%A9s%20-%20Tramo%205_final.pdf

Badger, R., & White, G. (2000). A process genre approach to teaching writing. ELT Journal, 54(2), 153-160. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/54.2.153

Bayat, N. (2014). The effect of the process writing approach on writing success and anxiety. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 14(3), 1133–1141.

British Educational Research Association (2018). Ethical guidelines for educational research (4th ed.). https://www.bera.ac.uk/researchers-resources/publications/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2018

Brisk, S. (2006). Language, Culture, and Community in Teacher Education. Routledge.

British Council. (n.d.). Product and process writing: A comparison. https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/professional-development/teachers/knowing-subject/articles/product-and-process-writing-comparison

Bryman, A. (2012). Social Research Methods. Oxford University Press.

Chen, J. (2023). Exploring imitative learning in a blended EFL writing class. ELT Journal, 78(3), 356-368. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccad039

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design (5th ed.). SAGE Publications.

Cummins, J. (1981). The role of primary language development in promoting educational success for language minority students. In California State Department of Education (Ed.), Schooling and language minority students: A theoretical framework (pp. 3-49). Evaluation, Dissemination and Assessment Center, California State University.

Díaz Maggioli, G. (2024). New Directions in Language Teaching. Grupo Magró Editores.

Dörnyei, Z., & Taguchi, T. (2010). Questionnaires in Second Language Research: Construction, Administration and Processing. (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Ellis, R. (2022). Does planning before writing help? Options for pre-task planning in the teaching of writing. ELT Journal, 76(1), 77-90. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccab051

Gibbons, P. (2009). English Learners, Academic Literacy, and Thinking: Learning in the Challenge Zone. Heinemann.

Halliday, M. A. K., & Matthiessen, C. M. (2004). An Introduction to Functional Grammar. Routledge.

Hayik, R. (2023). Engaging writing in the Arab EFL classroom. ELT Journal, 77(2), 156-169. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccac038

Hyland, K. (2003). Second language writing. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667251

Jiang, D., & Kalyuga, S. (2022). Learning English as a Foreign Language Skills in Collaborative Settings: A Cognitive Load Perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.932291

Mackey, A., & Gass, S. M. (2016). Second Language Research Methodology and Design (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Martin, J. R. (2009). Genre and Language Learning: A Social Semiotic Perspective. Linguistics and Education, 20(1), 10-21.

Mehrabi, N. (2014). The effect of second language writing ability on first language writing ability. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 4(8), 1719–1726.

Moon, J. (2008). L2 children and writing: A neglected skill? ELT Journal, 62(4), 398-400. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccn039

Raftari, S., & Abbasvand, M. (2023). Product, Process, and Genre Approaches to Writing: A Comparison. Iranian EFL Journal, 9(5), 75-85.

Suastra, M., & Menggo, S. (2020). Empowering Students’ Writing Skill through Performance Assessment. International Journal of Language Education 4(3) 432-441. https://doi.org/10.26858/ijole.v4i3.15060

Yasuda, S. (2011). Genre-based tasks in foreign language writing: Developing writers' genre awareness, linguistic knowledge, and writing competence. Journal of Second Language Writing, 20(2), 111-133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2011.03.001

Zamel, V. (1987). Recent Research on Writing Pedagogy. TESOL Quarterly, 21(4), 697-715.