Artificial

intelligence and otherness

Representations

of immigrants using generative image creation tools

Inteligencia

artificial y alteridad

Representaciones de inmigrantes usando

herramientas de creación generativa de imágenes

Inteligência

artificial e alteridade

Representações de imigrantes usando

ferramentas de criação de imagens generativas

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.18861/ic.2025.20.2.4108

ALEXANDRE

PROVIN

SBABO

alexandresbabo@gmail.com – Créteil – Université Paris-Est Créteil, France.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5231-0658

ALEXANDRE

MARCELO BUENO

alexandrembueno@gmail.com – São Paulo – Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie, Brazil.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0798-3615

HOW

TO CITE: Sbabo,

A. P.

& Bueno, A. M. (2025). Artificial

intelligence and otherness. Representations of immigrants using

generative image creation tools.

InMediaciones

de la Comunicación,

20(2).

https://doi.org/10.18861/ic.2025.20.2.4108

Submission

date: April 23, 2025

Acceptance date: September 20, 2025

ABSTRACT

We cannot deny, for better or for worse, that the democratization and accessibility of artificial intelligence represent an epistemological, social and technical turning point in society. In this context, it is necessary to investigate how tools for creating generative images represent and narrate the identities of people from a migrant background. On the basis of a common list of commands (prompts), entered in different geographical areas and in different languages, the purpose of this article is to determine whether the different tools generate representations that corroborate the maintenance of certain paradigms, such as those associated with stereotypes, or whether, on the contrary, they propose a different way of seeing the world by breaking with certain “received ideas” about immigrants. For this purpose, we use three different image generation tools, DALL-E 2, Midjourney and Stable Diffusion. The article presents two main aspects: the first, the establishment of a methodological research framework in relation to artificial intelligence tools; the second, the semiotic analysis of the results. The analysis of the images generated takes into account symbolic, political and expressive aspects, drawing on theoretical approaches from identity theories, sociosemiotics and discursive semiotics.

KEYWORDS: Artificial Intelligence, identity, representation, immigration, Semiotics.

RESUMEN

No podemos negar, para bien o para mal, que la democratización y accesibilidad de la inteligencia artificial representan un punto de inflexión epistemológico, social y técnico en la sociedad. En este contexto, se hace necesario investigar el modo en que las herramientas de creación de imágenes generativas representan y narran las identidades de las personas de origen inmigrante. A partir de una lista común de comandos (prompts), introducidos en diferentes áreas geográficas y en diferentes idiomas, el propósito de este artículo es determinar si las diferentes herramientas generan representaciones que corroboran el mantenimiento de ciertos paradigmas, como los asociados a los estereotipos, o si, por el contrario, proponen una forma diferente de ver el mundo rompiendo con ciertas “ideas recibidas” sobre los inmigrantes. Para ello, utilizamos tres herramientas diferentes de generación de imágenes, DALL-E 2 y Midjourney y Stable Diffusion. El artículo expone dos vertientes principales: la primera, el establecimiento de un esquema metodológico de investigación en relación con las herramientas de inteligencia artificial; la segunda, el análisis semiótico de los resultados. El análisis de las imágenes generadas tiene en cuenta aspectos simbólicos, políticos y enunciativos, basándose en planteamientos teóricos de las teorías de la identidad, la sociosemiótica y la semiótica discursiva.

PALABRAS CLAVE: inteligencia artificial, identidad, representación, inmigración, semiótica.

RESUMO

Não podemos negar, para o bem ou para o mal, que a democratização e a acessibilidade da inteligência artificial representam um divisor de águas epistemológico, social e técnico na sociedade. Neste contexto, torna-se necessário investigar a forma como as ferramentas de criação de imagens generativas representam e narram as identidades de pessoas de origem migrante. Com base em uma lista comum de comandos (prompts), inseridos em diferentes áreas geográficas e em diferentes idiomas, nosso objetivo será verificar se as diferentes ferramentas geram representações que corroboram a manutenção de certos paradigmas, como aqueles associados a estereótipos, ou se, ao contrário, propõem uma maneira diferente de ver o mundo, rompendo com certas “ideias preconcebidas” sobre os imigrantes. Para isso, utilizamos três ferramentas diferentes de geração de imagens, DALL-E 2, Midjourney e Stable Diffusion. O artigo expõe duas vertentes principais: a primeira, o estabelecimento de uma estrutura metodológica de pesquisa em relação às ferramentas de inteligência artificial; a segunda, a análise semiótica dos resultados. A análise das imagens geradas leva em consideração aspectos simbólicos, políticos e enunciativos, com base em abordagens teóricas das teorias da identidade, da sociossemiótica e da semiótica discursiva.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: inteligência artificial, identidade, representação, imigração, semiótica.

1.

INTRODUCTION

Discourses that present artificial intelligence as an “unstoppable technological revolution” –as for instance in the 2024 report by France’s Ministry of the Economy and Financei– are themselves symptomatic of a broader ideological framing. Rather than treating such claims as self-evident truths, it is important to interrogate how the rhetoric of inevitability shapes public perception and policy-making. What interests us in this field, therefore, is not AI as a technical object per se, but the ways in which it constructs, represents, and enunciates its own world of meanings.

In this paper, we examine the process of image creation using generative artificial intelligence (GAI) and its product (the produced image). Our objective is to observe whether the construction of visual utterances corresponds relatively to the semantic/lexical universe or to a meta-semiotic (Greimas, 1968). In other words, does the visual utterance created by GAI have a lexical/semantic signifying correspondence, or is it based on a universe of meaning “specific” to GAI? In this second case, what are the semantic limits of GAI? Is it possible to identify a production or reproduction of stereotypes in the images produced or, on the contrary, a kind of explosion (Lotman, 1999) of meaning?

As a complement to these questions, we will also attempt to determine if entering prompts in different languages and on different continents can have an impact on the image generated by the GAI, or if it represents a lexical and semiotic translation challenge for the different GAI tools.

For this purpose, we will focus on the figure of the migrant, but more specifically on the figure of the Brazilian migrant. There are three main reasons for this choice. The first is that the representation, the figure, or even the imaginary of the Brazilian individual presents itself as a real compositional challenge for the GAI, especially in light of the miscegenation of the Brazilian people. A complex hybridityii that goes beyond phenotypic traits and is also rooted in its practices (Fontanille, 2008, 2011), in its lifestyle (Landowski, 1997), in the “Brazilian way of being”. Complex hybridity which adopts the rhizomatic meaning of Deleuze and Guattari (1976), as well as that mentioned by the Grupo Comunicação, Cultura, Barroco e Mestiçagemiii, which

does not refer to the mixing of races, even if it includes it, obviously, but rather to the interaction between objects, forms and images of culture. (...) Miscegenationiv is a happy jaguar who feeds on all these Others (animals, people and objects)v. (Pinheiro, 2027, n.p.)

The second, personal and ethical, is that the authors of this text are also Brazilians. This allows us to talk about the Brazilians as Brazilians, and from a Brazilian point of view, rather than a Eurocentric or Americanized one, which enables us to identify the existence of clichés and inconsistencies with the representation of the Brazilians in a more precise way, even if this does not prevent us from having our own clichés. Thirdly, the term migrant, as we shall see in the first part of this text, refers to the context of the labour market, and this allows us to explore indirectly the production of stereotypes of the Brazilian, such as the soccer player or the Latino who works in the construction field. This kind of quest for the stereotype, following Beyart-Geslin's (2021) approach, gives us a glimpse of the creation of visual habits that contribute to the construction of a social image of the subject that subjects of any nationality, at any given moment, have to come up against.

The chosen methodology, which is more of a qualitative and comparative analysis, aims to establish a framework that is both neutral and impartial, without neglecting scientific rigor when it comes to corpus analyses. In terms of the theoretical basis of this study, the concepts of representation, enunciation and the logical pair narrativity/narrative will be our entry point for exploring the meaning of the images generated. This approach will then enable us to analyze our corpus in the light of symbolic, political and enunciative aspects, supported by approaches from identity theories, sociosemiotics and discursive semiotics.

It is true that the semiotic analysis of images is not new (Floch 1981a, 1981b, 1985; Thürlemann, 1982; Greimas, 1984). The same applies to the dialogue between semiotics and artificial intelligence (Meunier, 1989; Thérien, 1989; Arnold, 1989; Rialle, 1996). However, the particularity of this study, as is the case for most of the texts that study the production of images from GAI, is the fact that, at the start of our research, our corpus is virtual. In other words, our corpus is characterized by its “virtual existence (…) an existence ‘in absentia’” (Greimas & Courtés, 1979, p. 421), as a “shapeless and indistinctive mass” to borrow the expression from de Saussure (1931, p. 155).

In this way, following the example of other studies analyzing the visual productions of GAI (Dondero, 2024; D'Armenio, Deliège & Dondero, 2024), we have constructed our own corpus of 56 images, based on a prompt and with the assistance of the GAI. The particularity of our corpus lies not only in the symbolic and political character of the object of representation, the Brazilian migrant, but also in the methodology used to obtain them.

In order to satisfy a comparability criteria, the “meta-methodology” for the production of the images that constitute the corpus of this study is based on the respect of five basic criteria: (I) all images were generated with the same prompts, (II) prompts were translated into three different languages, Brazilian Portuguese, English and French, (III) prompts were entered in two different geographical areas, (IV) prompts were simultaneously entered, and (V) three platforms for image production from GAI were used: DALL-E 2, MidJourney 6.1 and Stable Diffusion 3.0. These five basic methodological criteria thus help us to evaluate the different responses and images created by each artificial intelligence from a common and comparable semantic base.

And as it is not possible to build a corpus from the GAI without a prompt, another methodological characteristic is essential: the “quality” of the prompt. We put the term “quality” in quotation marks here, because what can be considered a prompt of quality is quite variable and specific to each study. In this study, a prompt of quality must be as “neutral” as possible and should be semantically compatible in the different languages used, particularly in order to meet the criteria of reproductibility. Of course, we are also careful to place the word “neutral” in quotation marks, as we are aware that the very nature of our object and objective is impregnated by semantic and symbolic biases, particularly when working essentially with the notion of immigrant or migrant.

In fact, it is at this very point that we find our first major problem, since semantically, slight linguistic variations around the words “immigrant” and “migrant” could give rise to misleading synonyms. It is precisely for this reason that we are immediately forced to present the first definitions that will be useful to us throughout this work.

2.

THE SEMANTIC CHALLENGE OF THE PROMPT

When it comes to the semantics of the prompt methodology, we are compelled to face up to the different values and meanings of the words that surround the concept of “immigrant” and “migrant”, which is why our first step is lexical. This is the only way that we will be able to grasp which term would be best suited to establishing a simple, “neutral” and comparable prompt.

We emphasize that this lexical approach is crucial to ensuring that the prompt works properly overall, especially because the simplicity and efficiency we are aiming for will enable us to make our request to the GAI without giving too many hints, allowing the machine to “express itself” as “freely” and as “neutral” as possible. Our aim with this prompt is therefore to provide what we want, while allowing the machine to carry out its interpretation of the semantic and syntagmatic variables, i.e., what it considers, from its database, to be “immigrant”, “migrant”, “immigrant”, “foreigner” and its respective representations and constructions associated with these concepts.

This being the case, it seems appropriate to begin our approach by investigating the definition of the term that best defines the subject whose representation we are seeking: the person of immigrant background. On this point, Lacroix (2016,) offers a petit lexique des migrations in which he sets out the definition of migrant, immigrant and foreigner. For the author, “the term migrant is a generic term used to describe anyone living elsewhere than in their place of birth” (p. 19)vi. Thus, in his interpretation, “a migrant is a person who has carried out a migration, a journey through space to change their living place” (p. 19)vii. As for the term immigrant, Lacroix explains that it “designates people living in a state other than the one in which they were born” (p. 20)viii. The difference here is that the point of view adopted to refer to the immigrant is that of the country of reception or settlement. Finally, the author points out that “A foreigner is one who is of foreign nationality” (p. 21)ix, or stateless.

The problem with the definitions presented by Lacroix (2016)x is that they seem to slightly differ from those established by some dictionaries, and in addition they do not encompass the entire lexical spectrum of neighboring terms. We are thinking here in particular of the relationship between the lexemes /immigrant/migrant. In French, a quick look at the Centre National de Ressources Textuelles et Lexicales (CNTRL) reveals a clear difference between the frameworks of the terms. For the CNTRL (n.d.), migrant is defined as “the individual working in a country other than their own”xi, while immigrant is “those who immigrate (to another country country)xii, i.e., the person who comes “to a foreign country and settle there, often permanently”xiii. Similarly, Le Robert (n.d.) defines immigrant as “a person who immigrates to a country or has recently immigrated there”xiv, and migrant as “a person who expatriates for economic reasons”xv. These semantic particularities are also found in the English language, as the Cambridge Dictionary (n.d.) presents the lexeme migrant as “a person that travels to a different country or place, often in order to find a work” and the term immigrant as “a person who has come to a different country in order to live there permanently”. Interestingly, the definition provided by the HOUAISS dictionary of Brazilian Portuguese (n.d) does not necessarily take into account this distinction, which is marked in other languages (even in other Latin languages), but highlights the transitive difference between the terms. According to the dictionary, in Brazilian Portuguese, an immigrant is “someone who has settled in a foreign country”xvi, while a migrant is “someone who periodically changes location, region, country, etc.”xvii.

We observe that the definitions set out by Lacroix (2016) are unable to account for the fine-grained semantic differences of the lexemes in question, particularly with regard to the aspectualization of the terms. We see, for example, that the term immigrant rather settles into a terminativity (“to settle there, often definitively” (CNTRL), while the lexeme migrant is projected into a durativity, where the process is still unfolding, in our case, the subject's change of country “for economic reasons”. However, the lexeme /foreigner/, raises no problems for us, as all the dictionaries mentioned agree with the definition presented by Lacroix (2016).

So, in order to meet our self-imposed requirements for the development of the prompt, and in line with our interest in the representation of people from a immigrant background in dialogue with the labour market, it seems more appropriate to name the subject of our prompt based on the lexeme /migrant/.

However, if we intend to analyze the representations of images generated by artificial intelligence that relate the person from an immigrant background to his or her host country in the context of a professional activity, the word migrant by itself is not enough as it only provides us with the subject of the sentence. For this reason, we need to add a few more elements to the prompt.

The first point we need to clarify is the nature of this migrant. A migrant can come from any country and have any nationality. Moreover, it seems to us that the discursive and symbolic construction of the migrant and his or her representation can change according to the relationship between the country of origin and the host country. For example, in the Brazilian imaginary, a German migrant is valued euphorically, while a Bolivian migrant is valued dysphorically. This “game” of representations and symbolic constructions, which takes into account the relationship between the country of origin and the host country, seems to be particularly important when our objects of study are images generated by artificial intelligences. As Davallon (1984) states, “the practices of receiving and producing images are the site of the reproduction of patterns of perception and thought, in both their embodied and objectified forms” (p. 123)xviii.

For these reasons, we feel it is necessary to include these two elements in our prompt: the migrant's nationality and the country of their destination. In particular, because these two elements will enable us to analyze the image as a “properly social phenomenon, belonging to practical logic, socially and historically produced and reproduced, according to which an image appears (and is called such) when it conforms [...] to its incorporated social representation” (Davallon, 1984, p. 119)xix.

In this sense, we chose France as the destination country for our prompt, mainly because of the diversity of profiles among people from immigrant backgrounds, as highlighted in the work of Almeida and Baeninger (2016). Moreover, in French society, many Brazilians are publicly recognized for their notoriety, particularly in sports, but also in television programs and in cinema. The diversity of these profiles, especially those enjoying public recognition, makes the challenge of representing Brazilians in France even more complexxx.

Another important element of our prompt is that we need to specify the type or kind of image we want. So, in order to obtain results as close as possible to a representation of reality, it seems appropriate to specify to the GAI that the type of image to be generated will correspond to a photo image.

As a result, the prompt we will use takes shape as follows: [request [<image type>] <nationality><migrant><in/to><host country>, which corresponds syntactically to <adjective><name><preposition>< proper name>. Thus, our prompt is structured as follows: [request / Can you create a [image type / photo-style image] with the following prompt:] [adjective / Brazilian] [noun / Migrant] [preposition / in] [proper noun / France]. This prompt was also designed considering the limitations of the three GAI, because, for instance, when we asked DALL-E to generate photo-realistic images, it informed us that it was unable to perform this task: “I cannot generate images that mimic real photographs. However, I can create an image with a highly realistic style that approximates the effect of a photograph. If you agree, I can proceed with that.

It also seems necessary to point out that, depending on the language used, the syntactic relationship between the terms in the prompt changes. However, we do not think it is necessary to demonstrate these changes in the different languages used to design each prompt.

Starting with the syntactic structure we had arrived at, we began to enter prompts using the same process for the different GAI tools, that is, first in Brazilian Portuguese, then in English and lastly in French, simultaneously in Brazil and France. It is important to stress that the number of queries for each language and for each GAI tool were the same. However, in some cases we encountered error messages during image generation. In these cases, so as not to influence the result produced by the GAI, we settled for the first results obtained, with no retouching or new requests. It is for this reason that in our corpus, it is possible to visualize unequal quantities of images in each situation and in each GAI. The prompts were captured on August 01, 2024.

3.

PROMPT

RESULTS AND IMAGE ANALYSIS - DALL-E

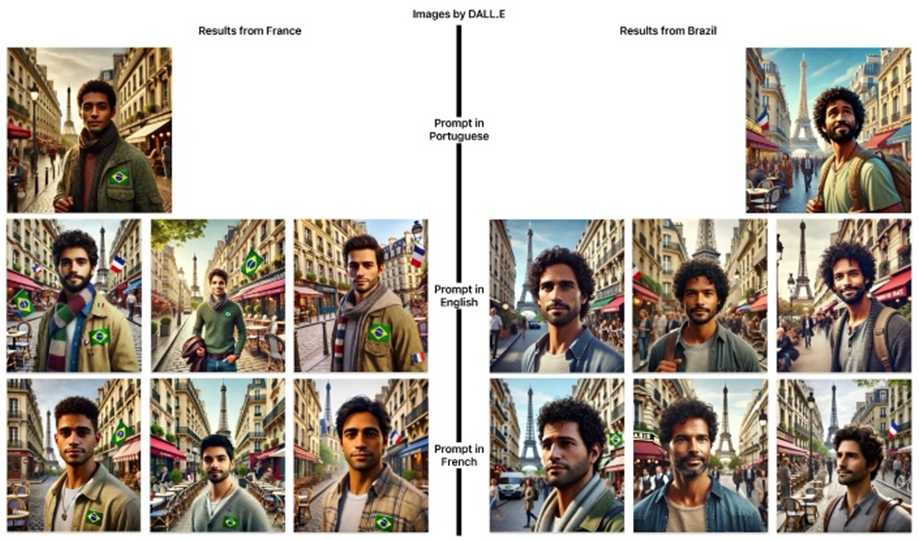

We then started with the DALL-E tool integrated into the GPT Chat platform from its paid plan (Image 1).

Image

1.

Table of images generated by DALL-E

Source:

Own elaboration based on the use of DALL-E.

For the prompt inserted from France, we obtained the image of a young black man wearing a jacket edged with a Brazilian flag on a street where the Eiffel Tower can be seen in the background. The same signifying arrangement is repeated from the prompt seized from Brazil: the image of a black man appears, but this time with plastic formants that make it closer to an illustration than to a photo or a realistic genre. However, there are no symbols or signs that would associate the subject of the image with Brazilian nationality.

In this particular case, we work d like to mention that we have chosen to consider only one of the results obtained, because at this stage of our research we work d already tested other prompts on the same platform. So, to avoid a vice in the tool, we have decided to consider only the results we present.

For the prompt entered in English from France, we note the generation of three images of men who are not necessarily white and who wear flags on their clothing, symbolically representing the two countries mentioned in the prompt. There is, however, only one image where the French flag does not appear either on the clothing or elsewhere, but in this one we find the word France legibly written. In addition, the images created by the DALL-E platform seem to reiterate the figurative anchoring of France through perhaps its main symbol (at least, abroad): the Eiffel Tower. The Eiffel Tower is almost always placed in the background of images from a perspective of Haussmann-style buildings. However, this figurative anchoring, constructed and marked by the monument, the architecture and the Brazilian and French flags, does not seem to contribute to the construction of the representation of what could semantically be understood as a migrant, since its figurativization can easily be mistaken with that of a tourist.

When it comes to the images generated from the English prompt entered from Brazil, a slightly different perspective emerges. Despite the reiteration of the same figurative anchoring strategies that place the discourse actors in a simulacrum of France, there are no obvious symbols linked to Brazil. It seems that, in this case, the platform has focused more on constituting the faces and bodies of these subjects (always men, by the way), who are represented as what might be called an average Brazilian, i.e. a “pardo”xxi subject, which is a concept used, incidentally, by the institute that carries out the census in Brazil. In this way, we see people who are neither white nor black, but who represent a mixture of the races. However, it must be understood that among the mixed-race population of Brazil –a country recognized as one of the most inequitable in the world (Gobetti, 2024)xxii– such a profile would not be so common, especially as one of the photosxxiii shows a face that is phenotypically more European.

When we move on to the prompt in French from France, we see a greater diversity in the representation of Brazilian immigrants in France. In this case, we find young people with the profile of mixed-race or black subjects, as well as Brazilians considered white (at least in the Brazilian context). However, in these images we find the same spatial configurations and the same figurative anchoring strategy as in the previous images.

All these characteristics are also reflected in the images generated by the French prompt entered from Brazil. In any case, it is clear that the representation of dark-skinned Brazilian immigrants on this platform is minimal. The same applies to the representation of migrant subjects in the strict sense of the word, as they seem to be figurativized more as tourists, though this may end up indicating a representation of France itself.

It seems to us, then, that DALL-E constructs a strategy of explicitness for the elements of the prompt, especially as regards the subject (a man, a foreigner) and the space into which he must fit: France (with its stereotypical symbols), while leaving aside the <work> seme associated with the <migrant> lexeme. This also makes us think that the construction of the figure of the migrant was not obvious, which instead leaves room for the figure of the foreigner, whose meanings can be broader (he can be a worker, he can be a tourist, he can be a refugee and he can even be French). In other words, the figurative construction of the GAI does not allow us to detach the thematic role of the “migrant”. In any case, at least the identification as a foreigner seems to have been preserved in this case. Furthermore, we note that in all the images generated from France, it is possible to observe a mise en scène of the Brazilian flag on the subjects' clothing in contrast to its absence in the results of the prompts produced from Brazil.

In this way, there seems to be a local attempt, from France, to mark the Brazilian presence in the image. Thus, the enunciative act of entering the prompt seems to indicate that the algorithm identifies the location of its user in a way that could possibly interfere in the production of the image, which would justify the iconic anchoring by the Brazilian flag. The finding that the same type of iconization does not occur in the Brazilian prompt may also indicate a question linked to the enunciatee, to which we do not yet have an answer, but which we hope to reflect on in future work.

This creates a face associated with Brazilian immigration. This face, which is therefore reiterated with few variations (in skin, shape, hair type), produces the meaning effect of a norm, as if Brazilians, on average, had the same traits that the images represent. In other words, a miscegenated subject is presented (who could obviously come from several countries, but not all of them) whose posture indicates an appropriate way to behave in his environment. Thus, even without any kind of anchoring to the Brazilian flag, it is possible to say that there is a recognition and identification with one of the phenotypes present in Brazilian society, since we are in the sociocultural dimension of face recognition –the biological and neurological perception of the face has already been explored, for example, by Leone, (2021)–. What we can not emphatically say is that he is a migrant (because he could be a tourist, a semantically closer example to the immigrant, among other possibilities), and we can not, of course, deny that he is in France.

Despite not being completely precise in its enunciative construction, DALL-E creates an image that can still be easily manipulated by other prompts to achieve the desired representation. In this way, we can say that we are getting closer to the image of an “ideal immigrant”, even if this image is only possible if we drastically reduce the ethnic diversity present in Brazilian society. In any case, the faces present in the images produced by DALL-E indicate a path towards the construction of a normative average Brazilian face, thus stabilizing the thematic role of nationality. However, for another thematic role (that of migrant), the platform did not have the same capacity to establish the representation of a stereotype. In the other platforms that will be analyzed below, this possibility is immediately discarded, as will be seen

4.

PROMPT RESULTS AND IMAGE ANALYSIS - MIDJOURNEY

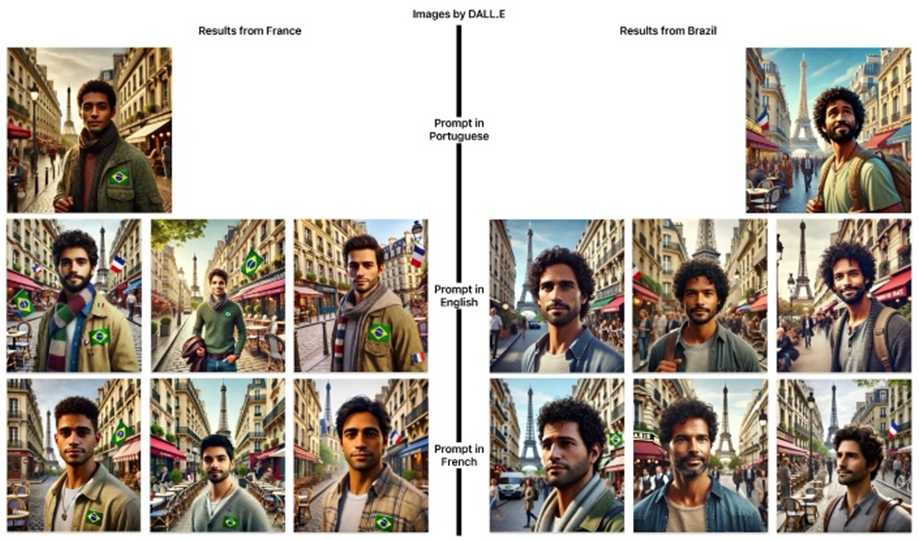

Let's move on to the second platform we used, Midjourney (Image 2). Following the same procedure, we obtained the following results.

Image

2.

Table of images generated by Midjourney

Source:

Own elaboration based on the use of Midjourney.

In this platform, the results of prompts entered in both Brazil and France are broadly similar. We note that the images generated by Midjourney from the Brazilian Portuguese prompt almost always refer to the figurativeness of subjects who can be identified more as refugees, and who we cannot necessarily associate with Brazil. In many cases, they are black men, in precarious situations, with large backpacks, figurativized in dysphoric scenarios, such as surrounded by garbage, in a rainy train station, even on a boat in the middle of the sea and sometimes with the presence of the Eiffel Tower.

As we can see, the various images figuratize what might rather be considered a refugee in a spatial anchorage that could be anywhere in the world. Indeed, the only images that establish a link with Brazil are those generated from Brazil. The first shows a white man carrying the Brazilian flag, with its associated colors, against a background that may not be directly associated with France. The second shows a black man with a parrot, a bird symbolically associated with Brazil, in a background that could be in France, but without any symbolic anchorage.

In the case of the prompt entered in English, we obtained similar results, with no major differences regardless of the country in which the prompt was entered. In these images, we find a majority of people in a possible situation of refuge in a spatial anchorage that sometimes dialogues with Haussmannian architecture, and also in a rather cold and rainy environment.

The same considerations can be made in relation to the images generated from the prompt entered in French in both Brazil and France.

What we can see is that on the Midjourney platform, we notice a reiteration of the focus on the faces of the actors in the so-called refugee discourse, based on an aesthetic that reminds us of the journalistic image and that often appears in reports aimed at constructing a human and individual aura, in other words, a subjectivation of the situation of refugees today.

By “mistaking” a migrant for a refugee, Midjourney highlights a semantic trait that does not appear in dictionaries, but which is produced and disseminated through other discourses, especially in the media, which associate immigration and refuge with the poverty and misery of people who have to flee their country. The semantic trait of precariousness that runs through the images reinforces the expectations generated by the presence of immigrants or refugees in certain situations, which then leads to the construction of suffering faces (no one is smiling or expressing happiness) of subjects who, even if they achieve their goal (to reach a city, for example), will continue to be precarious and remain excluded from the social sphere, because they already bear the marks of segregation and stigmatization, constructed by their skin color, their hair, their tense expression, among other elements. As a result, Midjourney reinforces a stereotype that is often the target of prejudice and racism because, at first glance, they are subjects who do not conform to the norms established in a relatively homogeneous society such as European and North American societies.

It should also be mentioned that there is an obvious intensification of color in the images and, above all, in the faces that are supposed to represent Brazilian migrants in France. In this way, as we mentioned, there is room for the reiteration of figures who are commonly victims of racism. Massimo Leone (2021) makes an interesting comment about chromatic alteration and racism, based on Umberto Eco:

The issue of chromatic alteration in the perception of the face is particularly sensitive, since, as Umberto Eco already underlined in his comments on racism, there is a kind of automatic, spontaneous racism, which is not necessarily related to an ideology, but to the pressure of a visual common sense which, in a given ethnic group, determines the ideal face or at least a range of acceptable variations. (p. 208)xxiv

However, for the author, it is not enough to perceive the other as an alterity based on physiological elements to be considered racist. It is also necessary to insert this alterity into a social and cultural universe in order for this other to be seen as, in the author's words, an anthropological alterity. This is precisely the movement that a platform like Midjourney provokes in its enunciator: the image of human beings with an evaluative and ideological bias of dysphoric representation of a precarious condition (momentary or not, it does not matter). In other words, it is not just a mistake on the part of the machine, but the reproduction of imagery patterns that are present in societies.

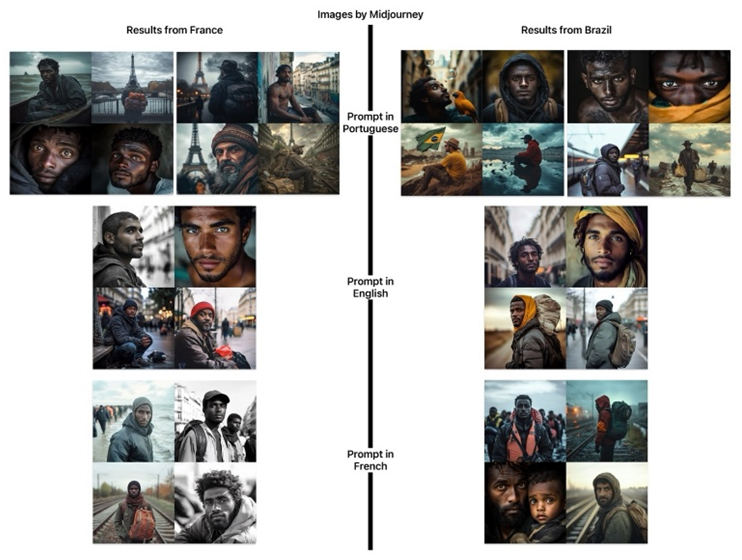

Lastly, Midjourney also seems to create images that can be interpreted as a form of mythical valorization (Floch, 1986). These are portrait images that present a different framing from the “journalistic” record, either by presenting an unexpected close-up, or by a play of light and contrasts. In this case, the images produced by Midjourney place the refugees in a situation of quasi-models, in other words, of an aesthetic that partly suspends their precarious condition in order to highlight a beauty that escapes misery and is sometimes even considered “exotic”. An obvious example of this is the classic portrait published on the cover of National Geographic in 1985, photographed by Steve McCurry (Image 3).

Image

3.

National

Geographic

magazine cover image

Source:

National

Geographic

(June, 1985).

Not surprisingly, it is a portrait of an Afghan refugee named Sharbat Gula (Strochlic, 2017). This image has become an example of how the media can manipulate the meanings of an image by suspending the misery of a certain degrading situation in an aesthetic object based on features that refer to the notion of Western hegemonic beauty. In this case, it seems that Midjourney also plays with these elements in some of the images produced from the same prompt used on other platforms.

5.

PROMPT RESULTS AND IMAGE ANALYSIS - STABLE DIFFUSION

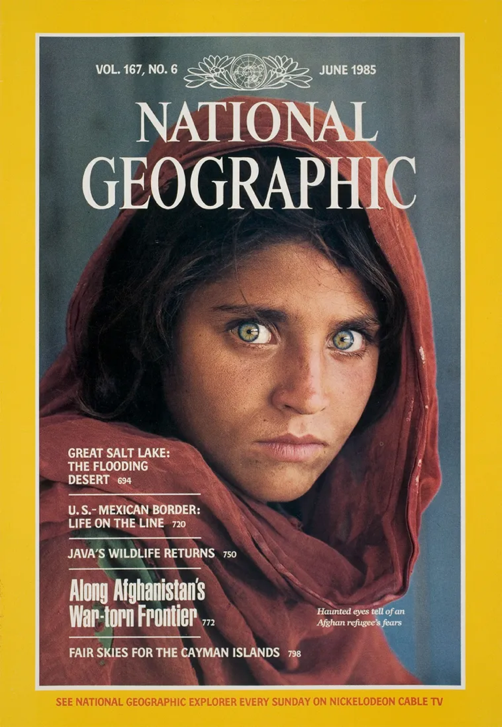

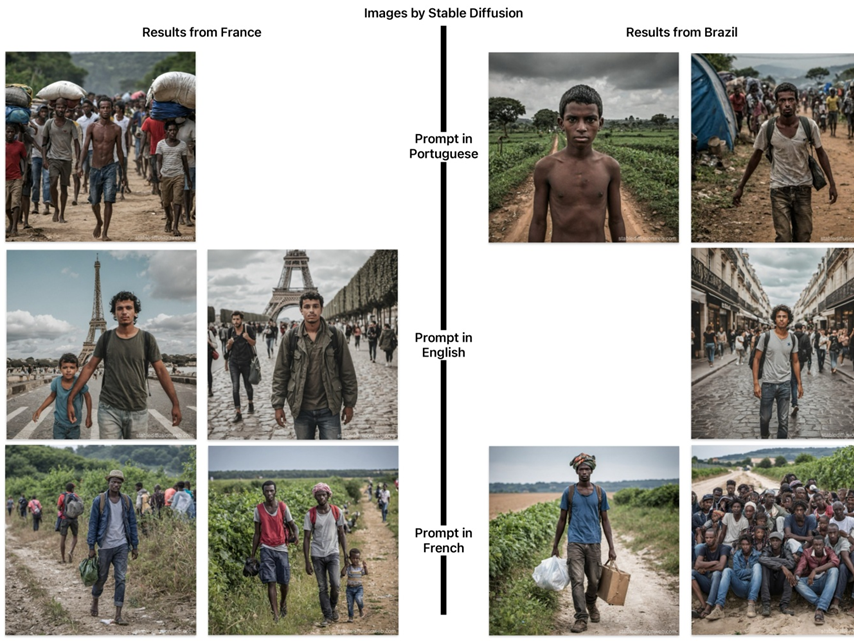

Following the same procedure, we move on to the final GAI image tool, Stable Diffusion (Image 4).

Image

4.

Table of images generated by Stable Diffusion

Source:

Own elaboration based on the use of Stable Diffusion.

The images that were generated from the Portuguese prompt in this platform reiterated the figurativization of refuge and refugee, ignoring however the semantic difference with the theme of immigration, migrant and also the spatial anchorage referred to by the word <France>. Of the four images produced, only one shows a city that could be recognized as being located in France. However, in the image in question, the representation of the subject refers to a citizen who could be from several countries other than Brazil.

Regarding the results of the images generated from the English prompt, we observe the reiteration of elements that have previously been highlighted by the DALL-E platform, namely, the presence of mixed-race men that can possibly be associated with the phenotypic representation of the Brazilian, as well as a spatial anchoring that refers to France thanks to the presence of the Eiffel Tower.

Compared to the images whose prompt was captured in French, we note the same elements of the prompt captured in Portuguese, i.e., absence of spatial anchoring, reiteration of the refuge theme, figurativization of the refugee and absence of semantic difference between refugee/migrant, as we observed with the production of Midjourney images. In other words, neutralizing the differences between immigrants and refugees reinforces the stereotyping of both social groups by emphasizing poverty and precarious living conditions as a common element for both types of foreigner.

As for the English prompt, the image of a mixed-race subject, but with traits closer to those of a white subject, also brings into question racial representation and, above all, the representation of the diversity of a given society. We therefore raise a question to open up a debate that cannot be developed in the space of this text: is stereotyping the limit of artificial intelligence in producing images of populations? Or will algorithmic technology allow us, in the near future, to expand the possibility of obtaining results that are closer to a social “reality” given through perception and experience?

6.

CONCLUSION

The results of the images generated by the platforms can be divided into two groups. On the one hand, we believe that this perspective of using stereotypes was a strategy of the tools to create images based on simple, generalist prompts aimed precisely at forcing the platforms to create an average Brazilian migrant somewhere in France. Clearly, the challenge we posed to the AI stems from the fact that an “average Brazilian” does not exist in itself, particularly in light of the complex diversity previously discussed. Nevertheless, through this challenge, we anticipated a broader phenotypic and situational diversity –an expectation that was not met in the results obtained.

On the other hand, still in the field of stereotypes and given the broad, general formulation of the prompts, we observed the production of images that went beyond the objectives of what a “neutral” representation of a Brazilian migrant in France should be, since there was an apparent confusion between the meaning of migrant and refugee, as well as many images that ignored the French space.

This conflation, however, generated important results for reflecting on what can be inferred from the stereotypes linked to the semantic field of migration and refuge: a) that there is a reiteration of the seme “poverty”, even if to different degrees (the refugee as being poorer and more miserable than the migrant), b) a marked racial cut (the refugee has a darker skin tone than the Brazilian migrant, which also reproduces the racial cut of Brazilian migrants, since the black population in Brazil is mostly poorer than the mixed-race and white populations), c) the platforms are also gendered, with a predominance of male adults and children (something to be explored further in future work), and d) still very simple forms of actor and spatial anchoring linked to the thematic role of migrant, nationality and geographical space.

In addition, we note the total absence of semantic complexity with regard to the lexeme <migrant>, as no image generation tool has captured the meaning of this term in relation to the notion of work that is associated with this word, as we have seen from dictionary definitions.

Even if we have not succeeded in achieving our primary objective, since that objective was to analyze the stereotypes of people from immigrant backgrounds and the results obtained were, for the most part, associated with a refugee situation, this work has enabled us to identify some of the limitations of GAI image tools, and has also provided us with some answers.

Regarding limitations, we are thinking in particular of the question of semantic depth, because as we have seen, no platform has explored the word migrant in the sense of the dictionaries, i.e., by relating the <work> seme; in the same sense, we have noticed that there is a linguistic limitation at the level of language translation. The results on Stable Diffusion were significantly different when the prompt entered was in English.

In terms of responses, we can say that the geographical location of users did not have a significant impact on image results. However, as we pointed out in our analysis, in some cases we found more or less marked reiterations depending on the geographical location from which the prompt was entered. Nevertheless, due to our small sample, we cannot confirm whether or not these enunciative strategies were influenced by this. In future work, we therefore plan to widen the geographical radius of our search, as well as the nationalities and situations represented in our prompts, in order to get closer to an answer. In other words, the problem of translating and interpreting the term “migrant” led us not to a representation of a person from Brazilian immigration, but rather to a refugee. This is why expanding this study could provide us with more information on a certain selectivity by the algorithms between the terms “migrant” and “refugee” –depending on nationality, for example– and their respective representations.

In this sense, this approach will also enable us to identify in the future works the long-term progression of the technical competence of GAI tools in the creation of images, to observe its semantic competencexxv and to evaluate a possible evolution of the discursive construction of GAI to societal representations over time. This possibility of continuity and expansion in this study is perhaps its greatest asset.

This leads us to say that, despite the promise of artificial intelligence, especially in terms of accelerating the process of constructing verbal, visual or syncretic texts, it still comes up against its limits, which are those of the data sets with which each model has been trained and also those of the mankind.

REFERENCES

Almeida, G. M. R. de & Baeninger, R. (2016). A imigração brasileira na França: do tipo histórico às modalidades migratórias contemporâneas. Revista brasileira de estudos de população, 33(1), 129-154. https://doi.org/10.20947/S0102-309820160007

Arnold, M. (1989). La sémiotique: un instrument pour la représentation des connaissances en intelligence artificielle. Études littéraires, 21(3), 81-90. https://doi.org/10.7202/500872ar

Beyaert-Geslin, A. (2021). L’invention de l’autre: Le juif, le noir, le paysan, l’alien. Classiques Garnier.

Cambridge English Dictionary. (n.d.). Immigrant. In Cambridge English Dictionary. Cambridge University Press. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/immigrant

Cambridge English Dictionary. (n.d.). Migrant. In Cambridge English Dictionary (online). Cambridge University Press. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/migrant

Centre National de Ressources Textuelles et Lexicales. (n.d.). Immigrant. In CNRTL lexical resource. CNRTL. https://www.cnrtl.fr/definition/immigrant

Centre National de Ressources Textuelles et Lexicales. (n.d.). Migrant. In CNRTL lexical resource. CNRTL. https://www.cnrtl.fr/definition/migrant

Commission de l’intelligence artificielle. Ministère de l'Économie, des Finances et de la Relance (2024). IA: Notre ambition pour la France. Gouvernement. https://www.economie.gouv.fr/files/files/directions_services/cge/commission-IA.pdf

D’Armenio, E., Deliège, A. & Dondero, M. G. (2024). Semiotics of Machinic Co-Enunciation. Signata. http://journals.openedition.org/signata/5290

Davallon, J. (1984). Sociosémiotique des images. Langage et société, 28(2), 111-140.

Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. (1976). Rhizome. Minuit.

Dondero, M. G. (2020). Les langages de l’image. De la peinture aux Big Visual Data. Hermann.

Dondero, M. G. (2024). Inteligência artificial e enunciação: análise de grandes coleções de imagens e geração automática via Midjourney. Todas as letras. Revista de língua e literatura, 26(2), 1-24. https://editorarevistas.mackenzie.br/index.php/tl/article/view/17164

Floch, J.-M. (1981a). Kandinsky: sémiotique d'un discours plastique non figuratif. Communications, 34.

Floch, J.-M. (1981b). Sémiotique plastique et langage publicitaire. Actes Sémiotiques, Documents EHESS - CNRS, 3(26).

Floch, J.-M. (1985). Petites mythologies de l’œil et de l’esprit. Pour une sémiotique plastique. Hadès Benjamins.

Floch, J.-M. (1986). Les formes de l’empreinte. Pierre Fanlac.

Fontanille, J. (2008). Pratiques Sémiotiques. Presses Universitaires de France.

Fontanille, J. (2011). L’analyse du cours d’action: des pratiques et des corps. Semen, 32. http://journals.openedition.org/semen/9396

Fontanille, J. (2016). Sémiotique du discours. PULIM.

Gobetti, S. (2024). Concentração de renda no topo: novas revelações pelos dados do IRPF. Observatório de Política Fiscal. https://observatorio-politica-fiscal.ibre.fgv.br/politica-economica/pesquisa-academica/concentracao-de-renda-no-topo-novas-revelacoes-pelos-dados-do

Greimas, A. J. & Courtés, J. (1979). Sémiotique: dictionnaire raisonné de la théorie du langage. Hachette.

Greimas, A. J. (1968). Conditions d'une sémiotique du monde naturel. Langages, 10(3), 3-35.

Greimas, A. J. (1984). Sémiotique figurative et sémiotique plastique. Actes Sémiotiques - Documents EHESS - CNRS, VI, 60.

Houaiss, A. (n.d.). Imigrante. In Houaiss dictionary of Brazilian Portuguese. Instituto Antônio Houaiss. https://houaiss.uol.com.br/busca?palavra=imigrante

Houaiss, A. (n.d.). Migrante. In Houaiss dictionary of Brazilian Portuguese. Instituto Antônio Houaiss. https://houaiss.uol.com.br/busca?palavra=migrante

Lacroix, T. (2016). Migrants: L'impasse européenne. Armand Colin.

Landowski, E. (1997). Présences de l’autre. Essais de socio-sémiotique II. Presses Université de France.

Leone, M. (2021). Mala Cara: Normalidad y alteridad en la percepción y en la representación del rostro Humano. Signa: Revista de la Asociación Española de Semiótica, 30, 191-211. https://doi.org/10.5944/signa.vol30.2021.29305

Le Robert. (n.d.). Immigrant. In Le Robert online dictionary. Le Robert. https://dictionnaire.lerobert.com/definition/immigrant

Le Robert. (n.d.). Migrant. In Le Robert online dictionary. Le Robert. https://dictionnaire.lerobert.com/definition/migrant

Lotman, Y. (1999). La semiosphère. PULIM.

Meunier, J. G. (1989). Artificial intelligence and the theory of Sign. Semiotica, 77(1-3), 43-63.

Pinheiro, A. (2017). A condição mestiça. https://escritablog.blogspot.com/2019/03/a-condicao-mestica-amalio-pinheiro.html

Picanço Cruz, E., Queiroz Falcão, R. P. de, Silva, M. L, da & Neves Penna, B. das (2021). Research report: Profile of Brazilians in France. Programa Institucional de Bolsas de Iniciação Científica FUNADESP-UNIGRANRIO. https://mpeinternacional.uff.br/wp-content/uploads/sites/53/2021/03/Relatorio-Brasileiros-na-Franca_FINAL.pdf

Rialle, V. (1996). IA et sujet humain: entre physis et sémiosis. Intellectica. Revue de l'Association pour la Recherche Cognitive, 23, 121-153. https://www.persee.fr/doc/intel_0769-4113_1996_num_23_2_1533

Saussure, F. (1931). Cours de Linguistique Générale. Payot.

Strochlic, N. (2017). Famosa “menina afegã” finalmente consegue um lar. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographicbrasil.com/sharbat-gula/2017/12/famosa-menina-afega-finalmente-consegue-um-lar-capa-historica-refugiado-afeganistao

Thérien, G. (1989). Sémiotique et intelligence artificielle. Études littéraires, 21(3), 67-80. https://doi.org/10.7202/500871ar

Thürlemann, F. (1982). Paul Klee, analyse sémiotique de trois peintures. Age d’Homme.

*

Author contribution: The conception of the scientific work was

carried out by Alexandre Provin Sbabo and Alexandre Marcelo Bueno.

All authors contributed to the design, material preparation, data

collection and analysis. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

* Note: the Academic Committee of the journal approved the publication of the article.

* The dataset that supports the results of this study is not available for public use. The research data will be made available to reviewers, if required.

![]()

Article published in open access under the Creative Commons License - Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

IDENTIFICATION

OF THE AUTHORS

Alexandre

Provin Sbabo. PhD

in Language Sciences by the University of Limoges (France) and PhD in

Communication and Semiotics by the Pontífícia Universidade Católica

de São Paulo (Brasil). Associate professor at the University

Institute of Technology of the Université Paris-Est Créteil

(France). Associate research member of the Centre d'étude des

discours, images, textes, écrits et communication and the Centre de

Recherches Sémiotiques in France and of the Centro de Pesquisas

Sociossémioticas in Brazil. Treasurer of the Fédération Romane de

Sémiotique and head of communication at the International

Association for Semiotic Studies.

Alexandre Marcelo Bueno. PhD in Linguistics and Semiotics by the Universidade de São Paulo (Brazil). Coordinator and Professor of the M.A. and PhD Program in Linguistics and Literature at Mackenzie Presbyterian University (Brazil). Member of the Executive Committee of the International Association for Semiotics Studies.

i Commission de l’intelligence artificielle, Ministère de l'Économie, des Finances et de la Relance (2024). See: https://www.economie.gouv.fr/files/files/ directions_services/cge/commission-IA.pdf

ii The term complex hybridity used here is an approximate translation of the Portuguese term “miscegenação/mestiçagem”, which refers to the cultural, linguistic, social, and symbolic blending associated with the identity construction of the Brazilian people.

iii This notion of miscegenation mentioned by the Grupo Comunicação, Cultura, Barroco e Mestiçagem is published on the home page of the research group's website. It can be accessed via this link: https://www5.pucsp.br/barroco-mestico/

iv We have decided to retain the term “miscegenation” here in order to remain as faithful as possible to the Portuguese text. However, as mentioned in footnote number 2, this term refers to the meaning of miscigenação/mestiçagem in Portuguese without any pejorative connotation.

v In the original text: “Mestiçagem aqui não remete ao cruzamento de raças, ainda que obviamente o inclua, mas à interação entre objetos, formas e imagens da cultura. (...) A mestiçagem é uma onça alegre que se alimenta de todas esses outros (bichos, gentes, objetos)” (Pinheiro, 2017, n.p.).

vi In the original text: “le terme de migrant est un terme générique qui permet de qualifier toute personne qui vit ailleurs que sur son lieu de naissance”.

vii In the original text: “un migrant est une personne qui a effectué une migration, un voyage dans l’espace pour changer de lieu de vie”.

viii In the original text: “désigne les personnes vivant dans un autre État que celui dans lequel elles sont nées”

ix In the original text: “un étranger est celui qui est de nationalité étrangère”.

x Due to space constraints, it was not possible to include other definitions of immigrant, migrant, and emigrant in the debate. In future work, to be developed based on the results of this study, we will reflect on this issue in order to better understand the relationship between the possible lexical definitions in question and the production of images.

xi In the original text: “l’individu travaillant dans un pays autre que le sien”.

xii In the original text: “celui ou celle qui immigre (dans un autre pays)”.

xiii In the original text: “dans un pays étranger pour s’y établir, souvent définitivement”.

xiv In the original text: “personne qui immigre dans un pays ou qui y a immigré récemment”.

xv In the original text: “personne qui s’expatrie pour des raisons économiques”.

xvi In the original text: “quem se estabeleceu em país estrangeiro”.

xvii In the original text: “que muda periodicamente de lugar região, país, etc.”.

xviii In the original text: “les pratiques de réception et de production des images sont le lieu de la reproduction des schèmes de perception et de pensée, sous leur forme incorporée comme sous leur forme objectivée”.

xixIn the original text: “phénomène proprement social, relevant de la logique pratique, socialement et historiquement produit et reproduit, selon lequel une image paraît (et est dénommée telle) lorsqu'elle est conforme (…) à sa représentation sociale incorporée”

xx There is no reliable census of Brazilian immigrants in France. However, in the report entitled Research report: Profile of Brazilians in France (Picanço Cruz, Queiroz Falcão, da Silva & Neves Penna, 2021), the profile of Brazilian immigrants in France is predominantly young, with the majority of individuals between the ages of 21 and 30 and with a college degree. There is a predominance of women, representing 75.2% of survey respondents. The main motivations for migration are family reasons, a better quality of life, and less violence, in addition to work and study opportunities. Most respondents immigrated between 1 and 4.9 years ago, suggesting a recent increase in Brazilian immigration to France.

xxi Since there is no perfect equivalent in English for the term “pardo”, we have chosen to keep it in Brazilian Portuguese. In Brazil, "pardo" is an official racial category, reflecting the country’s complex history of racial mixing.

xxiiAll the numbers os this research are available here: https://observatorio-politica-fiscal.ibre.fgv.br/politica-economica/pesquisa-academica/concentracao-de-renda-no-topo-novas-revelacoes-pelos-dados-do - Accessed February 19, 2025.

xxiii The image you see in the middle of the results of the prompt entered in English from Brazil.

xxiv In the original text: “El tema de la alteración cromática en la percepción del rostro es particularmente sensible, ya que, como Umberto Eco lo subrayaba ya en sus comentarios sobre el racismo, existe una especie de racismo automático, espontáneo, que no está necesariamente relacionado a una ideología, sino a la presión de un sentido común visual el cual, en un determinado grupo étnico, determina el rostro ideal o por lo menos una gama de variaciones aceptables”.

xxv What we refer to here as semantic competence is the AI’s ability to interpret a word according to its different meanings, without reproducing errors or flaws in meaning. In other words, is the traduction/interpretation ability.